Federal Deficit in the Danger Zone

As federal spending continues to rise, a crushing mountain of debt looms.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

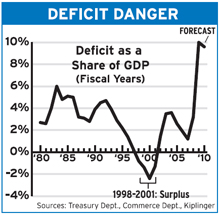

Time is running out for attacking the deficit. The danger, once distant, is now close. Soaring deficits are jacking up the national debt, resulting in higher interest rates and raising the odds of an even weaker dollar, which would stunt economic growth and lower Americans’ future standard of living.

Spending is out of control. For years it has averaged about 20% of GDP. This year, it’ll be about 25%. Some of that is due to spending on war in the Middle East as well as efforts to cushion the effects of the recession through higher unemployment benefits, aid to banks and state governments, spending on roads and highways, and more. Plus, tax receipts diminished as the economy shrank.

But even after the economy fully recovers, outlays won’t ebb. The growing ranks of retirees mean that Medicare and Medicaid costs will keep soaring, even if health care reform successfully curbs increases in the cost of care -- an iffy proposition at best.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Such entitlement programs -- those that lawmakers don’t control on a year-to-year basis but that run on a sort of autopilot -- account for 54% of federal spending. And they’ve climbed 6.4% on average a year since 2000. When it comes to spending that it can control annually, Congress has shown little restraint. Discretionary spending, which includes defense and an array of domestic programs from national parks to the FBI, has risen over the past decade at an average of 7.5% a year.

The result is an annual deficit that in fiscal 2009 was equal to nearly 10% of GDP, the largest since it hit 21.5% in 1945 at the end of World War II. What’s worse is that a mountain of debt will continue to pile up even if the politicians in Washington manage to keep a rein on spending and trim the yearly deficit. In fiscal 2009, federal debt held by the public jumped by a third, to $7.8 trillion. At the end of fiscal 2008, debt held by the public measured 41% of GDP. By 2014, it’ll equal a whopping two-thirds of GDP.

The interest payments on the debt will be staggering. They could soar to as much as $800 billion a year by the end of this decade, gobbling up 16% of the total budget. Indeed, servicing the debt may become the single biggest item in the federal budget, surpassing Medicare, defense and Social Security.

That will raise the cost of borrowing for everyone -- households and businesses alike. And it threatens to derail the U.S. economic engine. A jump in the debt from 40% of GDP to 60% would boost the rate on Treasury bonds by a full percentage point. Other interest rates, such as those for mortgages and corporate bonds, would follow. And if the U.S. loses its top credit rating -- until recently, an unimaginable event -- interest rates will increase even more. China, Saudi Arabia and other cash-rich nations would insist on higher returns to keep buying U.S. Treasuries at auctions.

Foreign nations, which own about half of the $7.8 trillion public debt, don’t need to sell to make waves. They could simply slow their rate of buying. That might tempt the Federal Reserve to buy debt in order to stave off a rise in interest rates. But that’s no way out. “Countries have tried that and seen double-digit inflation,” says Rudy Penner, former director of the Congressional Budget Office, now with the Urban Institute. “Even the tiniest probability of that has to be avoided.”

There are no easy fixes. Diane Swonk, chief economist with Mesirow Financial, says, “We’re going to have to cut overall spending and raise overall taxes.” In fact, solving the problem will take unparalleled restraint, and determination by elected officials of all stripes.

For weekly updates on topics to improve your business decisionmaking, click here.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

Humanoid Robots Are About to be Put to the Test

Humanoid Robots Are About to be Put to the TestThe Kiplinger Letter Robot makers are in a full-on sprint to take over factories, warehouses and homes, but lofty visions of rapid adoption are outpacing the technology’s reality.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

Disney’s Risky Acceptance of AI Videos

Disney’s Risky Acceptance of AI VideosThe Kiplinger Letter Disney will let fans run wild with AI-generated videos of its top characters. The move highlights the uneasy partnership between AI companies and Hollywood.

-

AI Appliances Aren’t Exciting Buyers…Yet

AI Appliances Aren’t Exciting Buyers…YetThe Kiplinger Letter Artificial intelligence is being embedded into all sorts of appliances. Now sellers need to get customers to care about AI-powered laundry.

-

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026The Kiplinger Letter Economic growth across the globe will be highly uneven, with some major economies accelerating while others hit the brakes.

-

The AI Boom Will Lift IT Spending Next Year

The AI Boom Will Lift IT Spending Next YearThe Kiplinger Letter 2026 will be one of strongest years for the IT industry since the PC boom and early days of the Web in the mid-1990s.