Interest Rates and the Real Unemployment Rate

There’s nothing magic about a particular unemployment rate. No one number is enough to indicate that the economy is healthy.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Don’t be surprised if the U.S. unemployment rate hits 6.5% and the Federal Reserve still doesn’t start raising interest rates. Several Fed officials, including the current chairman, Ben Bernanke, and the incoming chairman, Janet Yellen, have suggested that a jobless rate that low would indicate that the economy was healthy enough to wean from today’s record-low interest rates. Months before it hit that level, the Fed would also have begun to taper off its massive bond buying campaign, gradually reversing its policy of quantitative easing. At its current pace of decline -- a 0.8 percentage point drop over eight months -- the unemployment rate would hit the presumed trigger at the end of 2014.

But the odds are it’ll be well into 2015 before the country’s monetary gurus are comfortable ratcheting up the federal funds rate—the rate at which banks borrow from one another or the Fed itself, effectively setting short-term rates for everyone. Why?

Because there’s a lot more to assessing the country’s unemployment situation than just the percentage of the labor force that is actively seeking a job but can’t find one. For starters, there’s the question of exactly who is in the labor force. The government’s definition—anyone who holds down a job or is actively seeking a job—ignores a sizable number of people. Every month, millions join the labor force: Young folks seeking their first jobs, new immigrants to the country, stay-at-home moms and dads who go back to work once their children reach school age and more. Nearly the same number drop out: New retirees, people who develop disabilities and can no longer work and, sadly, folks who want to work but have become so discouraged that they quit hunting for positions.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Since the end of the recession in June 2009, the number of people leaving the labor force has climbed significantly. As a result, the labor force participation rate—the share of the total population that is either working or looking for a job—dropped from 65.7% to 63.2% in September 2013. (An upward blip in both the unemployment rate and the labor force participation rate in October was a distortion wrought by the partial government shutdown that month.)

At least four out of every 10 who dropped out of the labor force from June 2009 to September 2013 were jobless and likely too discouraged to keep looking for work. The largest decline in the labor force participation rate over that 51-month period was for males ages 25 to 29, clearly not retirees eager to spend their golden years on the golf course. Once these folks stop looking for work, the government figures they’re no longer in the labor force, so they’re no longer counted as involuntarily unemployed. And the unemployment rate goes down.

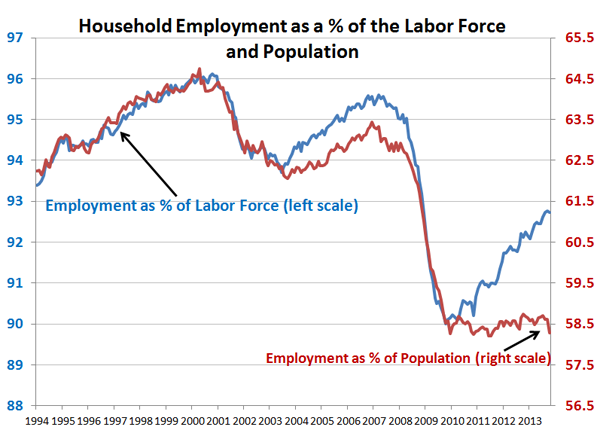

Fortunately, there are other ways to help gauge what’s really going on. Take a look at the chart below. It shows employment as a share of the labor force in blue. It’s essentially the unemployment rate upside down—a 7% unemployment rate means a 93% employment rate. As you might expect, the blue line drops during the recessions of 2001 and 2008-2009, and it rises after the recessions. The red line, which tracks employment as a share of the civilian population ages 16 and up is in sync with the blue line through the economic expansion of the 1990s and during the recession-spurred declines. But the two lines diverge in the periods that follow the recessions when people leave the labor force. The employed as a share of the labor force rises, but as a share of population, not so much. The flat trend since 2009 indicates that employment is keeping pace with population growth but isn’t recovering to its prerecession share.

If discouraged job seekers don’t come back into the labor force anytime soon, the Fed can treat a 6.5% jobless rate as a signal that recovery is assured and stop goosing the economy with easy money. But if some or all of the disaffected workers do start hunting for jobs again, the declining jobless rate will reverse course. And the wise men and women of the Federal Reserve know that. So they’re unlikely to start withdrawing monetary policy props for the economy too swiftly, perhaps waiting to see some upward movement in the red line. It will probably be 2015 before short-term interest rates begin to rise.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

David is both staff economist and reporter for The Kiplinger Letter, overseeing Kiplinger forecasts for the U.S. and world economies. Previously, he was senior principal economist in the Center for Forecasting and Modeling at IHS/GlobalInsight, and an economist in the Chief Economist's Office of the U.S. Department of Commerce. David has co-written weekly reports on economic conditions since 1992, and has forecasted GDP and its components since 1995, beating the Blue Chip Indicators forecasts two-thirds of the time. David is a Certified Business Economist as recognized by the National Association for Business Economics. He has two master's degrees and is ABD in economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026The Kiplinger Letter Economic growth across the globe will be highly uneven, with some major economies accelerating while others hit the brakes.

-

Amid Mounting Uncertainty: Five Forecasts About AI

Amid Mounting Uncertainty: Five Forecasts About AIThe Kiplinger Letter With the risk of overspending on AI data centers hotly debated, here are some forecasts about AI that we can make with some confidence.

-

Worried About an AI Bubble? Here’s What You Need to Know

Worried About an AI Bubble? Here’s What You Need to KnowThe Kiplinger Letter Though AI is a transformative technology, it’s worth paying attention to the rising economic and financial risks. Here’s some guidance to navigate AI’s future.

-

Will AI Videos Disrupt Social Media?

Will AI Videos Disrupt Social Media?The Kiplinger Letter With the introduction of OpenAI’s new AI social media app, Sora, the internet is about to be flooded with startling AI-generated videos.

-

What Services Are Open During the Government Shutdown?

What Services Are Open During the Government Shutdown?The Kiplinger Letter As the shutdown drags on, many basic federal services will increasingly be affected.