Even Now, Firms Struggle To Find Skilled Staff

There may be plenty of workers in the market, but too few have the education and skills needed to do the job.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Believe it or not, many businesses are finding it tough to hire the kind of workers they need. Even in the throes of a recession, a range of companies haven’t been able to fill some critical job openings.

There are plenty of applicants, but many lack the right skills. It’s not a labor shortage per se, but a dearth of talent. In fact, over 60% of businesses say it’s difficult to find qualified workers. Despite the loss of about 8 million jobs since the recession began, manufacturers as a whole have continued to seek machinists and machine operators, welders, laser die cutters and other highly skilled laborers. And engineers -- chemical, nuclear, environmental and others with special training -- remain in short supply, as do scientists. Demand for nurses and nursing teachers, physician assistants, physical therapists, pharmacists and other health care workers outstrips supply. Ditto, skilled information technology workers, from systems analysts to programmers.

The problem will get progressively worse, hitting a wider swath of companies, now that the economy has begun to perk up, with company layoffs waning and total U.S. employment likely to grow by about 1 million jobs in the coming year.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

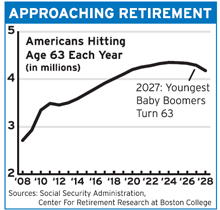

Adding to the shortage: The most educated and skilled workers are starting to retire. Baby boomers -- the generation born between 1946 and 1964 -- represent about 40% of the current labor force. As a group, they not only have considerably more education than preceding generations, but also more than the generation that follows them, not to mention decades of invaluable on-the-job training. Nearly 58% of baby boomers have at least some college under their belts. That compares with less than 55% of Americans who were born between 1965 and 1988. From 2008 to 2018, about 34 million workers will retire or shift occupations, requiring employers to scramble for replacements. That represents more than two-thirds of the nearly 50 million job openings that are expected during the period, a much greater rate of replacement for skilled workers than employers have had to deal with in past decades.

What’s more, newly created jobs are more likely to require higher education than in the past. About 31% of all jobs now require a postsecondary degree of some sort. Over the next decade, the percentage will creep up.

Plus, too few students are interested in pursuing the science, technology, engineering and math skills that employers need. From 2004 to 2014, occupations in science and engineering are expected to grow at nearly double the rate for all occupations. The 30 occupations likely to grow fastest over the next decade lean distinctly toward science and math, and include software engineer, biochemist and biophysicist, physician assistant, medical scientist, veterinarian and veterinarian assistant, among others. The two fastest growing occupations: Biomedical engineer, likely to grow by over 70% from 2004 to 2014, and network systems & data communications analyst, up 53%.

Also worrisome: Nearly all the growth comes from foreigners earning degrees. More than half of the U.S. doctorates awarded in 2005 for engineering, mathematics, computer sciences, physics and economics went to students with temporary visas. For years, education has been a key U.S. export, as enterprising young men and women from India, China, South Korea, Brazil, Nigeria and other developing economies flock to American universities and colleges to earn bachelor’s and graduate degrees.

American businesses have benefited from that because many of the students never go home, choosing instead to put their degrees to work for U.S. employers. But that advantage is likely to wane in coming years as improving economies in China and India, for example, brighten the prospects for careers back home.

The picture is no brighter for the two-thirds of jobs that don’t require an advanced education. Too many folks aren’t qualified even for them, having not finished high school. Three out of 10 don’t get a degree in four years. And many who do still lack even basic skills, according to employers. Too often, they can’t read well enough to fill out job applications, much less to understand instructions or training materials needed to do the job. Plus, they frequently lack the communication skills to undergo a job interview.

A skilled labor force is key to remaining competitive in a global economy, and the U.S. is falling behind. “Unless we as a country have an educated workforce, a skilled workforce, one that is able to compete in world markets, we are going to fall behind, and indeed there is some reason to believe that has already started to happen,” says Arthur J. Rothkopf, senior vice president at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

In one comparative study, American youngsters scored above average in math and science, but eighth-graders in Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, Hungary and Russia, among others, did better in math, while the U.S. ranked 11th in science. In another study, 15-year-old Americans scored below average, falling behind teens in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, New Zealand, Canada, Japan and others. In math alone, the U.S. ranked 32nd.

Critics blame the U.S.’ mediocre performance on several educational differences:

-- Briefer school days and shorter school years than in some rival countries. Finland and Switzerland, for example, have 10 additional school days per year. In South Korea, it’s 40, and in Japan, over 60 more days.

-- Inferior textbooks, less knowledgeable teachers and less demanding classes. For example, math students in Singapore use textbooks that aim for a deep grasp of mathematical concepts. In contrast, U.S. textbooks typically focus on formulas and definitions.

-- The lack of tough national standards, such as those developed by Germany starting a decade ago or those in force in Singapore, Japan and Hong Kong.

-- And at least one education advocacy group blames the U.S. focus on tests of basic reading and math skills. Their claim: Students in high performing nations such as Japan and Finland spend more time developing critical-thinking skills by doing chemistry experiments, reading poetry and studying history, for example.

As the U.S. mulls how to address education policy, the Obama administration is working with business groups and Congress on a variety of issues, many of which will be the focus of debate in Congress in 2010 and 2011. Businesses warn that there’s no time to waste.

For weekly updates on topics to improve your business decisionmaking, click here.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

An Inflection Point for the Entertainment Industry

An Inflection Point for the Entertainment IndustryThe Kiplinger Letter The entertainment industry is shifting as movie and TV companies face fierce competition, fight for attention and cope with artificial intelligence.

-

Humanoid Robots Are About to be Put to the Test

Humanoid Robots Are About to be Put to the TestThe Kiplinger Letter Robot makers are in a full-on sprint to take over factories, warehouses and homes, but lofty visions of rapid adoption are outpacing the technology’s reality.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026

The Kiplinger Letter's 10 Forecasts for 2026The Kiplinger Letter Here are some of the biggest events and trends in economics, politics and tech that will shape the new year.

-

Disney’s Risky Acceptance of AI Videos

Disney’s Risky Acceptance of AI VideosThe Kiplinger Letter Disney will let fans run wild with AI-generated videos of its top characters. The move highlights the uneasy partnership between AI companies and Hollywood.

-

AI Appliances Aren’t Exciting Buyers…Yet

AI Appliances Aren’t Exciting Buyers…YetThe Kiplinger Letter Artificial intelligence is being embedded into all sorts of appliances. Now sellers need to get customers to care about AI-powered laundry.

-

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026

What to Expect from the Global Economy in 2026The Kiplinger Letter Economic growth across the globe will be highly uneven, with some major economies accelerating while others hit the brakes.