Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

By Michael Stratford

1. Hey, big spenders. During the 2008 campaign cycle, donors poured more than $5 billion into federal elections. This election season, even more money is likely to flood in, because it’s the first presidential election since several court decisions loosened campaign-finance rules.

2. The sky is not (always) the limit. According to federal election law, individuals may donate up to $2,500 per candidate per election (the primary and general elections are counted separately), up to $30,800 to a national political party annually, and up to $10,000 to state, district and local parties combined each year. Individual donations to issues-oriented political action committees (PACs) are capped at $5,000 per year. Anyone may contribute unlimited sums to nonprofit advocacy groups—often dubbed 501(c)(4)s after the tax-code provision that governs them—and to independent-expenditure-only committees, or “Super-PACs.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

3. Make a connection. A direct donation to a candidate’s campaign often offers the most bang for your buck, says Michael Beckel, spokesman for the Center for Responsive Politics. A contribution of, say, $1,000 might yield, depending on the district, special access to current or future elected officials, Beckel says. Campaigns prefer direct donations (even if they’re small), especially early in the race.

4. Donate to a cause. If you are more concerned about a particular issue than electing a candidate, you might want to donate to an advocacy group—such as Planned Parenthood or the National Pro-Life Alliance—which can then decide where your money is needed most. PACs may use contributions to promote their viewpoint, but they are prohibited from expressly promoting or attacking a candidate. Super-PACs may promote or critique a specific candidate, as long as they don’t coordinate with another candidate or a political party.

5. Follow the money. Candidates are prohibited from spending campaign money on personal expenses, such as a new car or baseball tickets, but PACs and Super-PACs aren’t bound by those rules. “There are very few restrictions on what a political organization can do with its money,” says Paul Ryan, a lawyer at the Campaign Legal Center. Still, PACs and Super-PACs must disclose their spending in regular reports, which are available on the Federal Election Commission’s Web site.

6. Let the sunshine in. At the federal level, if you donate more than $200 to a candidate, political party, PAC or Super-PAC, your name, address, occupation and the amount of your contribution will become publicly available through FEC filings. Large contributors, however, may donate privately to a 501(c)(4), which may turn the money over to a Super-PAC, effectively skirting the disclosure requirements.

7. Give to a nonprofit twin. Nearly every advocacy group, from the National Rifle Association to the Sierra Club, has a related 501(c)(3) charity, according to Beckel. So, if you want to support an organization in a general sense, a contribution to its charitable operations could be a good bet. Your money may not be used directly for political purposes, but if you itemize deductions, you will be able to write off the contribution on your federal tax return.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

How to Search For Foreclosures Near You: Best Websites for Listings

How to Search For Foreclosures Near You: Best Websites for ListingsMaking Your Money Last Searching for a foreclosed home? These top-rated foreclosure websites — including free, paid and government options — can help you find listings near you.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Is Relief from Shipping Woes Finally in Sight?

Is Relief from Shipping Woes Finally in Sight?business After years of supply chain snags, freight shipping is finally returning to something more like normal.

-

Economic Pain at a Food Pantry

Economic Pain at a Food Pantrypersonal finance The manager of this Boston-area nonprofit has had to scramble to find affordable food.

-

The Golden Age of Cinema Endures

The Golden Age of Cinema Enduressmall business About as old as talkies, the Music Box Theater has had to find new ways to attract movie lovers.

-

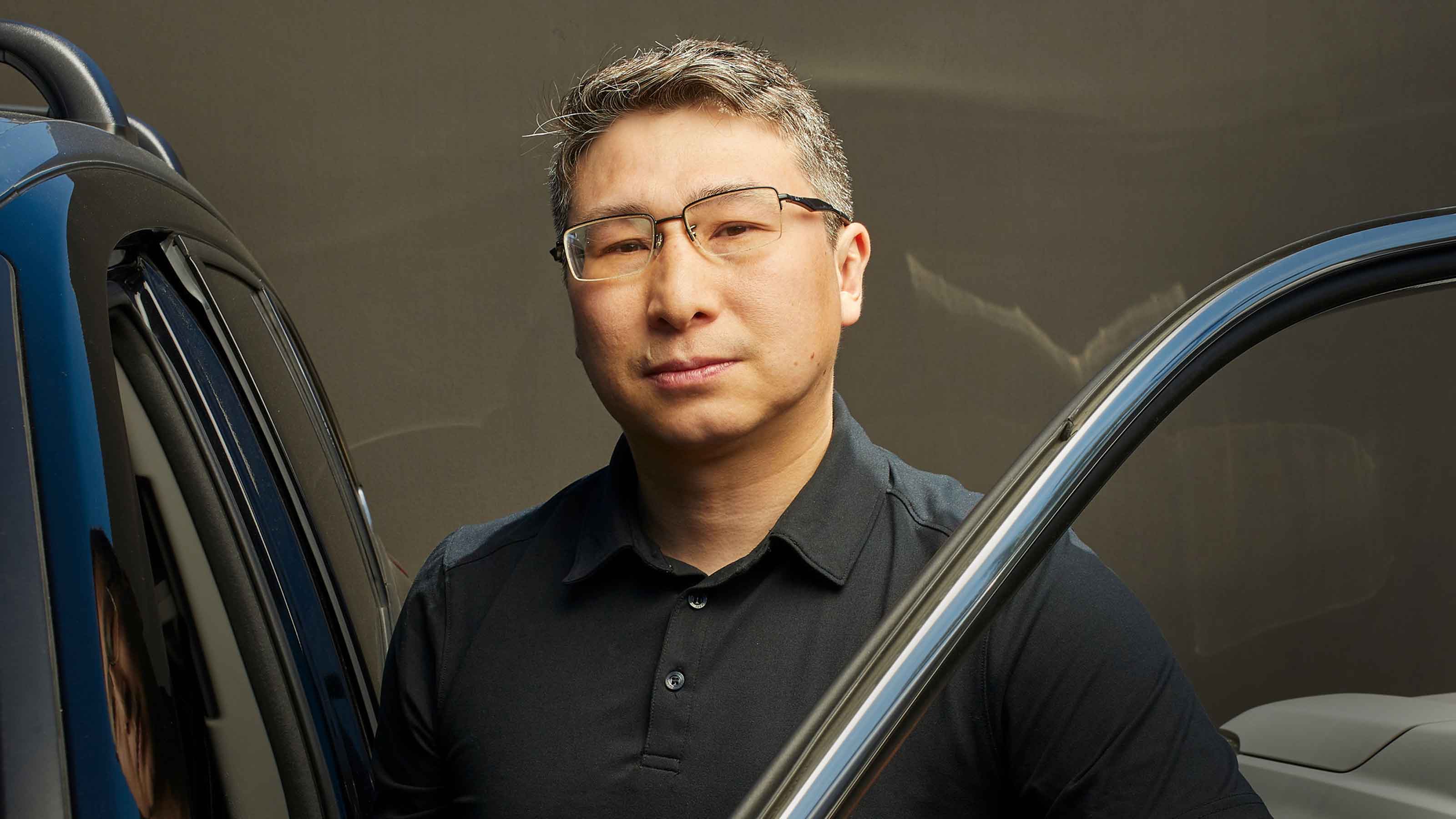

Pricey Gas Derails This Uber Driver

Pricey Gas Derails This Uber Driversmall business With rising gas prices, one Uber driver struggles to maintain his livelihood.

-

Smart Strategies for Couples Who Run a Business Together

Smart Strategies for Couples Who Run a Business TogetherFinancial Planning Starting an enterprise with a spouse requires balancing two partnerships: the marriage and the business. And the stakes are never higher.

-

Fair Deals in a Tough Market

Fair Deals in a Tough Marketsmall business When you live and work in a small town, it’s not all about profit.