The March on Washington: A Personal Reflection

Editor-in-chief Knight Kiplinger looks back to a moment on the mall 50 years ago — and explores how far we've come in realizing the goals outlined that day.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

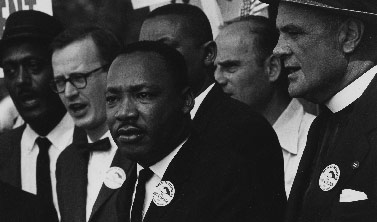

People don’t always know, at the time, that they are participating in a historic event. My brother and I, teenagers in the summer of 1963, certainly didn’t, as we strode toward the Mall with thousands of fellow Americans on a hot August morning.

We didn’t know we were part of the largest public gathering ever held in Washington up to that time.

And we didn’t know that this mass of 200,000-some people would play a key role in the passage a year later of the most important civil rights protections since the end of the Civil War: the right of racial minorities to patronize any public accommodation in the nation, be it a restaurant, hotel, rental housing, theater, park, restroom, amusement park or any other place open to the general public.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

A Family at the March

A few days before, our father — journalist and publisher Austin Kiplinger, then 44 years old and today a robust 94 — told us he would be participating in a demonstration for civil rights taking place in downtown D.C. (The Kiplinger family had long been supportive — as private citizens, employers and journalists — of equal rights for all.)

Dad said he would be marching with members of an anti-poverty group in Montgomery County, Md., our home suburb, and with a committee urging adoption of local and national fair-housing laws that would guarantee that people of any race could rent and buy homes in any neighborhood or apartment building. Montgomery County, like many other places in both the northern and southern states at the time, tolerated a range of discriminatory practices in public facilities.

My brother, Todd, who was then 17, and I, a 15-year-old rising high school junior, had already heard about the march on the evening TV news shows, and we wanted to come along.

Disorder or Peaceful Protest?

The organizers of the rally had made public assurances that their thousands of supporters, both black and white, would be coming in respectful support of a proposed open-accommodations law that was stalled in Congress.

Many in Washington were skeptical, fearing the worst. Some stores and offices were closed for the day, local people were urged to stay home, and the police were on high alert. But in our family, who lived in a rural area 20 miles from D.C. but who always felt comfortable in the city, there was no discussion of whether this mass rally would be peaceful and safe, just an assumption that it would be.

My father drove us into the city early on the morning of the rally and parked at the Kiplinger publishing offices, just a few blocks north of the Mall. He set off on foot to meet his fellow fair-housing marchers at the appointed place, Todd and I began walking toward the Lincoln Memorial, and we all agreed to meet back at the office in the afternoon.

First Impressions

Our first impressions of this event: It was huge (far bigger than we had expected), it was diverse, and it was a veritable love-fest.

Chartered buses from all over America, organized by civil rights groups, labor unions, churches, colleges and others, had apparently brought tens of thousands of people to the national capital.

Not only were these people — black and white, young and old — gathering peacefully, but the rally overflowed with a spirit of courtesy, brotherhood and confident hope for a better future.

By the time we got to the Mall, both sides of the Reflecting Pool — the shallow, rectangular lake running from the Lincoln Memorial to the Washington Monument — was packed with people.

The early arrivals had staked their claims with blankets and folding chairs, spreading out their picnic lunches. Later arrivals like us were standing shoulder to shoulder, milling around and carefully threading their way between the picnics to get as close as possible to the east steps of the Memorial, where the speeches would take place.

We didn’t get far, bogging down a long way from the edge of the Reflecting Pool and even farther from the Lincoln Memorial.

Missing the Speeches

So Todd and I, like many thousands that day, didn’t hear the eloquent orations that have resonated in the half-century since then. It was only that evening, watching the news on TV back at home, that we first heard the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. describe his passionate dream for a different American future. The words I heard on the broadcast that evening tingled in my spine, and, 50 years later, they still do.

But that afternoon, Todd and I had simply wandered among the crowd, chatting with other marchers, reading their homemade and professionally crafted signs, and taking note of interesting details.

We passed by one extremely tall man whom we — and everyone else, it seemed — recognized as Wilt “The Stilt” Chamberlain, star center of the NBA’s San Francisco Warriors. He was greeting well-wishers amiably, just another guy in the crowd.

We were struck by how well dressed everyone was, especially the African-Americans (whom every respectful person in that era, black and white, referred to as Negroes). Despite the sultry weather, most marchers were in suits, skirts and dresses, and many of the Negro women were in “Sunday go to meeting” attire, with high heels and nice hats.

After Tragedy, a Bill Triumphs

In the afterglow of the march, even after that inspirational day, it was still clear that passage of the civil rights legislation was a long shot. President John F. Kennedy, while championing the bill, could not persuade enough southern Democrats and midwestern Republicans to back it.

Everything changed three months later, with the assassination of Kennedy in Dallas. The new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, had enough clout among his old colleagues on the Hill to corral the needed votes, in part as a tribute to his slain predecessor. The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law in July, less than a year after the March on Washington.

One might have thought that it would usher in a new era of racial harmony in America, but it didn’t. States pushed back against its provisions and dragged their heels on enforcement. The focus of young black activists shifted from legal rights to economic issues in inner-city slums. Their rhetoric and tactics became confrontational, anti-white and violent. On top of this, the nation was becoming bitterly divided over the war in Vietnam.

A Time of Chaos — and New Hope

Over the next three years, deadly riots broke out in black neighborhoods of Los Angeles, northern New Jersey and Detroit. The nation was shaken by the assassination of the Rev. King in the spring of ’68 — followed by severe rioting in many cities, including Washington — and the murder of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in June.

During this chaotic time in America, my brother and I were students at Cornell, and we experienced this racial turmoil on our own campus. As a young idealist, committed to values of free speech, civil discourse and compromise — values being trampled by both the political left and right — I felt a deep despair about the course of my country.

How far we had fallen from the hopeful spirit of brotherhood I had felt that day on the Mall, just five years before.

It would take America many years to recover that spirit, and, arguably, it still hasn’t yet, despite remarkable and admirable economic and political achievements by racial minorities. The never-ending journey continues.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Knight came to Kiplinger in 1983, after 13 years in daily newspaper journalism, the last six as Washington bureau chief of the Ottaway Newspapers division of Dow Jones. A frequent speaker before business audiences, he has appeared on NPR, CNN, Fox and CNBC, among other networks. Knight contributes to the weekly Kiplinger Letter.

-

The New Reality for Entertainment

The New Reality for EntertainmentThe Kiplinger Letter The entertainment industry is shifting as movie and TV companies face fierce competition, fight for attention and cope with artificial intelligence.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost You

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost YouTaxable Income When Super Bowl LX hype fades, some fans may be surprised to learn that sports betting tax rules have shifted.

-

R.I.P.: A Good Journalist, Good Boss, Good Father

R.I.P.: A Good Journalist, Good Boss, Good Fatherbusiness Journalist and philanthropist Austin H. Kiplinger led the Kiplinger Washington Editors for decades.

-

What Our Readers Want

Economic Forecasts Our magazine readers are heavy users of electronic media, but they also love print on paper.

-

D.C.'s Economy Is Out of Touch

Economic Forecasts Flattening federal spending will give the region a taste of what the country has been going through.

-

Equality on the Job

business The long ascent of women workers has been hard-fought, and vestiges of male privilege remain.

-

The Future Is Yours

business Whatever quality of life means to you, achieving it is in your hands.

-

A Balanced Federal Budget? Not without Pain

Economic Forecasts Businesses and individuals who benefit from tax breaks must surrender some self-interest.

-

A Stubborn U.S. Budget

Economic Forecasts How can the federal government bring revenues and expenses back into balance?

-

Blame for the Bubble

Economic Forecasts One professor's take on how we got into this sorry mess is an insightful—and unsparing—account.