Should You Have a Right to Delete Personal Online Information?

Web sites should be obligated to comply with requests to remove information under certain circumstances.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Q. My friend and I disagree about whether people who are not in the public eye should have the legal right to force Web sites to remove (or search engines to unlink) any information about themselves that is erroneous, intimate or badly outdated. I say yes. But he says, “Internet content should live forever, like it or not.” What do you think?

A. I lean toward your position, but within limits. I believe that Web sites and search engines should be obligated to comply with requests to remove information (or block its easy retrieval) under certain circumstances, including the following:

-- The information is demonstrably false;

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

-- The information lacks important facts about the outcome of a bad situation—for example, that an arrest resulted in the charges being dropped or the accused person’s acquittal;

-- The negative information is so old—say, a story about a person’s youthful indiscretion or minor legal offense—that the individual is entitled to a fresh start, a “clean slate”;

-- The content (music, photography, literature, etc.) is protected by copyright and is being distributed without the owner’s consent;

-- The information reveals personal financial data that could be used for identity theft;

-- Intimate personal information—for example, about one’s health or private sexual activity—was posted not by the individual depicted, but by someone intent on humiliating her or him;

-- The online information was posted long ago by a youthful commentator—say, in an academic paper, online blog or column in a college newspaper—and expresses inflammatory opinions that were later disavowed by the writer.

These guidelines would help achieve a balance between two conflicting rights: on the one hand, the public’s right (actually, an insatiable and somewhat voyeuristic desire) to know or learn, through Web searches, virtually everything about everyone; and on the other hand, a nonpublic citizen’s right to “privacy by obscurity,” or the “right to be forgotten.”

Have a money-and-ethics question you’d like answered in this column? Write to editor in chief Knight Kiplinger at ethics@kiplinger.com.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Knight came to Kiplinger in 1983, after 13 years in daily newspaper journalism, the last six as Washington bureau chief of the Ottaway Newspapers division of Dow Jones. A frequent speaker before business audiences, he has appeared on NPR, CNN, Fox and CNBC, among other networks. Knight contributes to the weekly Kiplinger Letter.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

When Tech is Too Much

When Tech is Too MuchOur Kiplinger Retirement Report editor, David Crook, sounds off on the everyday annoyances of technology.

-

I Let AI Read Privacy Policies for Me. Here's What I Learned

I Let AI Read Privacy Policies for Me. Here's What I LearnedA reporter uses AI to review privacy policies, in an effort to better protect herself from fraud and scams.

-

What Is AI? Artificial Intelligence 101

What Is AI? Artificial Intelligence 101Artificial intelligence has sparked huge excitement among investors and businesses, but what exactly does the term mean?

-

Text-Generating AI Faces Major Legal Risks: Kiplinger Economic Forecasts

Text-Generating AI Faces Major Legal Risks: Kiplinger Economic ForecastsEconomic Forecasts Major legal risks to text-generating artificial intelligence: Kiplinger Economic Forecasts

-

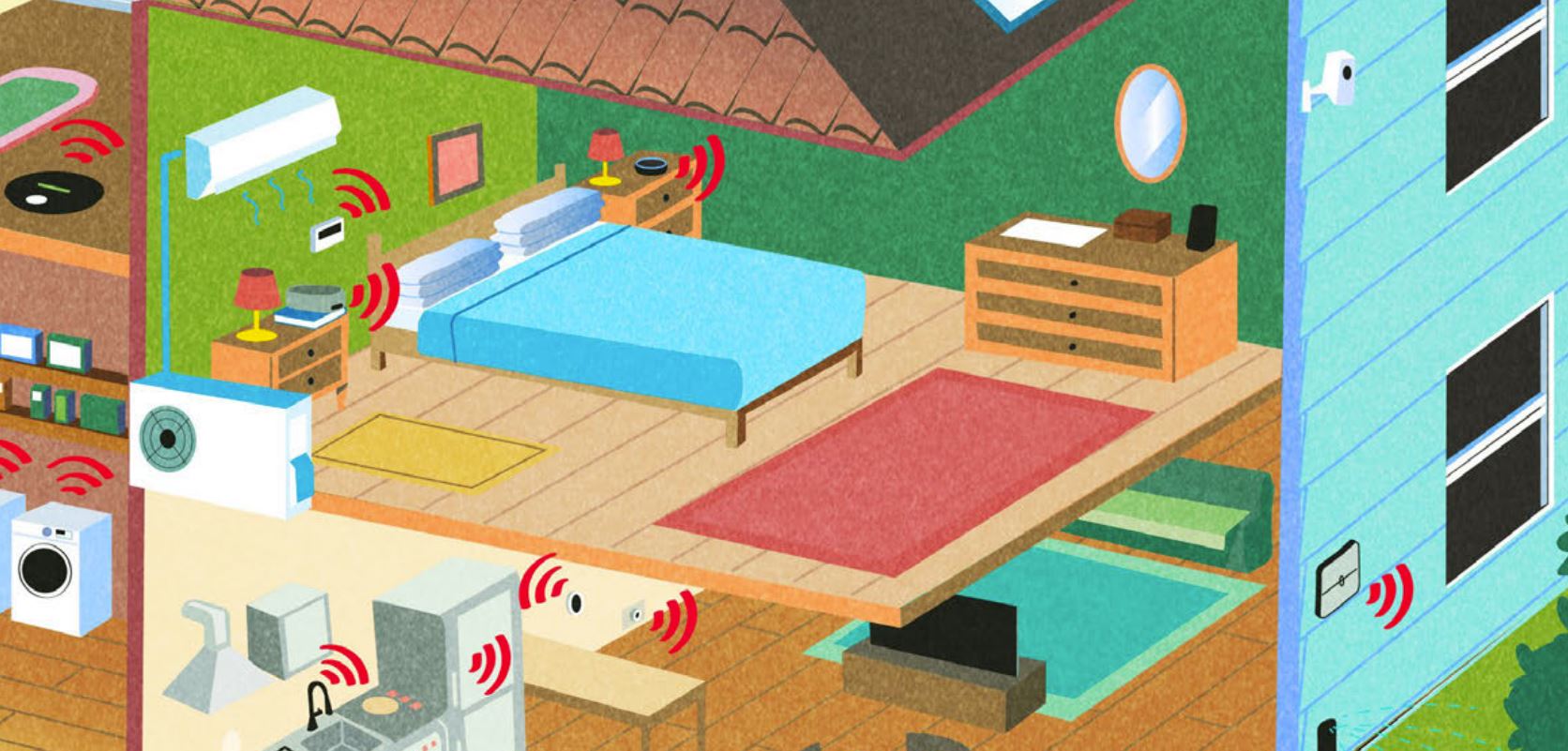

The 27 Best Smart Home Devices

The 27 Best Smart Home Devicesgadgets Innovations ranging from voice-activated faucets to robotic lawn mowers can easily boost your home’s IQ—and create more free time for you.

-

How to Choose the Right Payment App

How to Choose the Right Payment Appbanking Using PayPal, Venmo, Zelle and other apps is convenient, but there are pros and cons to each.

-

Shop for a New Wireless Plan and Save Big

Shop for a New Wireless Plan and Save BigSmart Buying Competition is fierce, and carriers are dangling free phones and streaming subscriptions.

-

Watch Out for Job Listing Fraud

Watch Out for Job Listing FraudScams If one of your New Year’s resolutions is to find new employment in 2022, be on guard against job-listing scams.