How to Pay for College

The tab for a four-year education is mind-boggling. But don’t panic: You don’t have to save the entire cost.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Vicki and George Petrides started saving for college shortly after their oldest daughter was born. Now Kaelyn, 18, is starting her second year at Virginia Tech, and her sisters, Laurel, 15, and Anna, 9, aren't too far behind. "With three children, college expenses are a big number to deal with," says George. By the time the Petrideses' daughters finish college, they could face a total tab of $500,000 or more. And the couple have long set their sights on getting all three of their daughters through their undergraduate years without any debt.

Their strategy for this gargantuan task? Start early, make use of all their options and check in periodically with their financial adviser to make sure they’re prioritizing college and retirement savings in a way that makes sense and maximizes tax breaks along the way. They got a head start on building their college kitty shortly after Kaelyn was born thanks to a contribution from Vicki's grandfather. Since then, the couple have been using a combination of 529 accounts, company stock from Vicki's job and mutual funds to save for college expenses. They will use their savings -- along with scholarships, financial aid and current income -- to pay the college bills. Plus, they plan to pay off a home-equity loan by next summer to help free up cash for current college expenses as well as beef up their college fund.

And though the Petrideses hope to keep student loans out of the mix, they expect their daughters to contribute financially to their education. By working during summer and semester breaks, they aim to save several thousand dollars to help pay for textbooks and personal expenses.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

How Much to Save

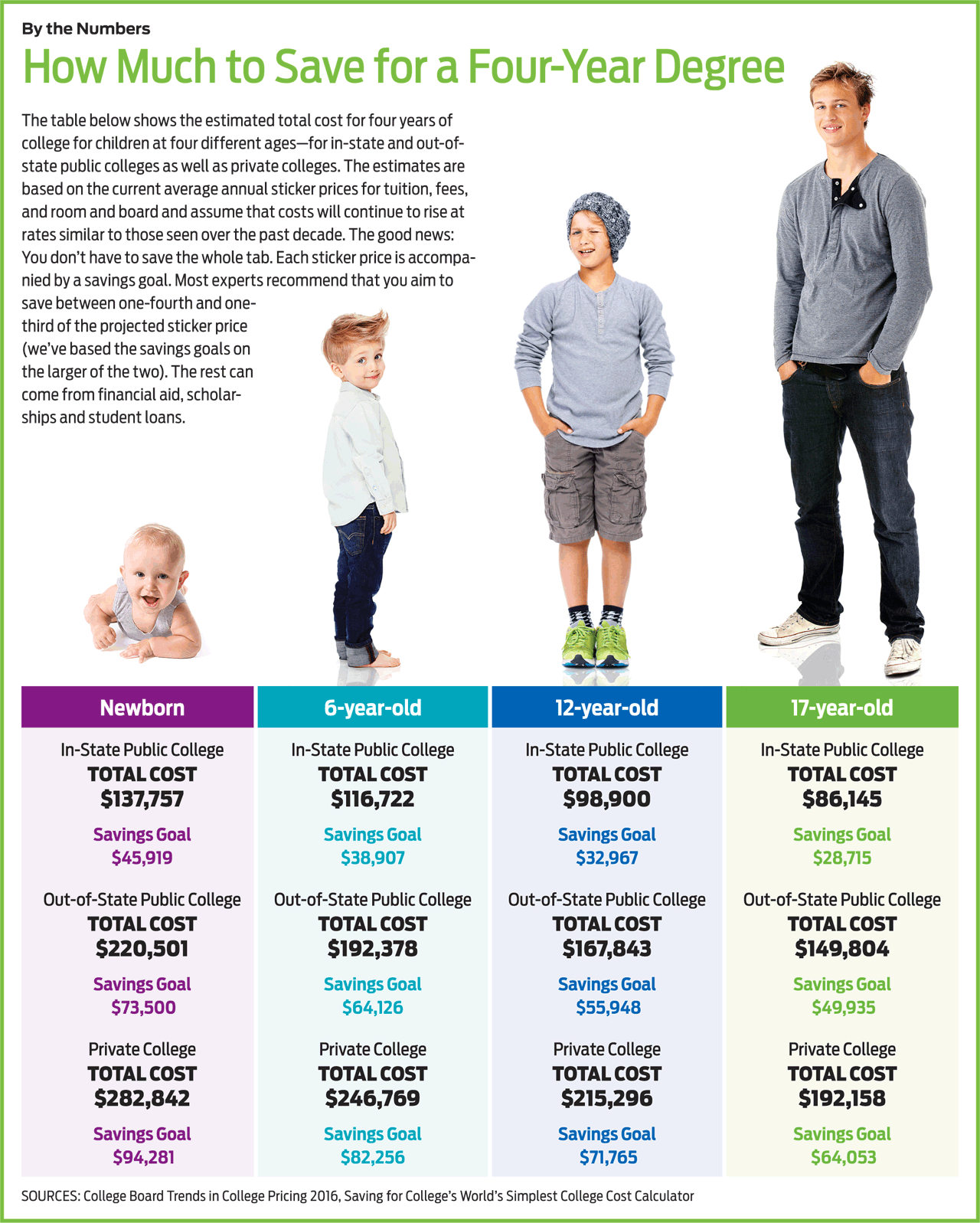

The average sticker price for the 2016–17 academic year at a four-year public institution, including tuition, fees, and room and board, was $20,090 for in-state students and $35,370 for out-of-state students, according to the College Board. The average tab at private colleges was $45,370, but many private schools post annual sticker prices north of $60,000.

It's tough to predict what college will cost by the time your child (or grandchild) enrolls. The steady rise in the cost of a college education continues, but the pace has slowed in recent years. Over the past decade, published figures for in-state tuition, fees, and room and board at public four-year colleges increased 32.4%, or 2.8% per year after inflation, whereas private four-year institutions increased 25.8%, or 2.3% per year after inflation. Similar increases over the next decade would push some schools' sticker prices to more than $75,000 per year, or more than $310,000 over four years. To get an estimate of the costs by the time your child heads off to college, use FinAid.org's College Cost Projector.

Such eye-popping sums may seem like an insurmountable obstacle, particularly if you're just starting to save or you have more than one child to send to college. But most families pay far less than a school's sticker price. At many schools, generous need-based-aid awards often reduce the school’s net price by 50% or more of the published price for families who qualify. Scholarships and non-need-based aid, also known as merit aid, can further reduce costs.

"Your biggest worry shouldn't be how much to save," says Brian Boswell, vice president of SavingforCollege.com. "Instead, worry about getting started—and soon." The longer you wait, the more difficult it will be to reach your savings goal. Although you have a variety of options, the savings vehicle of choice is the 529 college-savings account, which allows earnings to accumulate tax-free and usually offers state tax breaks for contributions. (See our guide to 529 college savings plans.)

Most experts recommend that you aim to save between one-fourth and one-third of the projected sticker price for each child. You'll generally be able to use a combination of scholarships, grants, loans and a portion of your current income when your child is enrolled to cover the rest of your college costs. Families with their eye on an in-state public university may want to use a slightly different strategy. Fidelity recommends multiplying your child's current age by $2,000 and comparing that figure to your savings efforts to get a quick read on whether you are on track to cover half the cost of an in-state public college.

For a clearer picture of your college-savings goal, you can use online tools to tailor that guideline to your family's circumstances. The SavingforCollege.com's College Cost Calculator creates an initial estimate of how much you need to save per month based on your child's age. But you can customize the results to also consider the cost of the school your child may attend, what portion of the projected costs you hope to cover, how much you have already saved and other details.

Although the federal financial aid formula and the details of your family's financial situation may change by the time your child reaches college age, it's still worth getting a rough idea of the kinds of financial aid your student may qualify for, says Carol Stack, coauthor of The Financial Aid Handbook. Start by using the FAFSA4caster tool. Later, once you have the short list of schools your child is interested in attending, visit each school's website to use its net price calculator. After providing some information about your student and your family's financial situation, you'll be able to see what families like yours paid to attend the previous year, after grants and scholarships.

Even if you think your household income is too high to qualify for aid, don't write off the possibility of receiving need-based aid. Many schools have generous definitions of who qualifies. And no matter what the FAFSA4caster or a net price calculator shows now, plan to rerun the calculations as your child gets closer to college and as your family's financial situation changes.

If you're saving for college for more than one child, you'll need to do some more math -- and some more saving. The number of dependents in the family and the number of children enrolled in college at the same time are considered as part of the federal financial aid formula and will reduce your expected family contribution, as well as boost how much need-based aid you qualify for. But those changes are often smaller than you might think, says Boswell. For example, in 2017–18 a family with four dependent children and a household income of $125,000 will likely qualify for about $5,000 more in financial aid than a family with the same income and one child.

The formula does, however, adjust your family contribution if you have more than one child enrolled in college at the same time. You can use the College Board's EFC calculator to see your estimated family contribution. A handful of schools offer programs that reduce tuition for families with more than one member enrolled at the school at the same time. For example, Saint Anselm College, in Manchester, N.H., offers a grant of $6,000 for each sibling who's enrolled beyond the first (split equally among them).

Where to Save

State 529 college-savings plans usually trump other savings options. They grow tax-free and let you skip taxes on earnings if the withdrawals are used for qualified education expenses. There’s no income limit to save in a 529, most states offer tax breaks for contributions, and the accounts have minimal impact on financial aid.

But a 529 isn't the only way to save. Some vehicles offer more flexibility or a broader range of investment options, and the various types of accounts affect financial aid in different ways. Some families choose to save in more than one type of account.

Prepaid plans. If you're sending your child to school in-state, prepaid plans allow you to lock in tuition at your state's public colleges years in advance. Most plans are available only to state residents and offer the same tax benefits and penalties as 529 plans. Currently, only 11 states offer plans that are open to new enrollees, but nearly 300 private colleges and universities allow you to prepay through the Private College 529 Plan.

All of the state plans require that you prepay several years before your child starts college and charge somewhat more than what tuition costs in the year you lock it in. If your child enrolls in a public college in another state or a private school, you can get a refund or transfer the money, but the amount may not cover all the costs.

Coverdells. Like 529s, Coverdell education savings accounts allow your savings to grow tax-free and escape taxes if used for qualified education expenses. Families that earn less than $220,000 per year in 2017 (or $110,000 for single filers) can set up an account at a bank or brokerage firm and contribute up to $2,000 per student each year until the beneficiary reaches age 18. Unlike 529 plans, qualified items for Coverdell funds include some costs for elementary and high school expenses. If you use the money for non-qualified items, you'll owe tax and a 10% penalty on earnings.

Roth IRAs. Withdrawing money from your own Roth IRA as a last-ditch effort to pay the tuition bill isn’t a great idea if those funds are important to a secure retirement. But the flexibility of a Roth means it could be part of your college savings strategy if you have a 401(k) plan or other ways to save for retirement.

You can currently contribute up to $5,500 per year, or $6,500, including catch-up contributions, if you're age 50 or older. (In 2017, the ability to contribute to a Roth IRA disappears after modified adjusted gross income exceeds $196,000 for married couples filing jointly or $133,000 for single filers.) Say both you and your spouse contribute the maximum amount to a Roth over 18 years (not including any catch-up contributions). If your investments earn 7% per year, you’ll have more than $400,000 on hand to pay for college.

Because you stash after-tax money in Roth accounts, you can withdraw contributions tax-free anytime. Withdrawals of earnings after age 59½ are tax-free if you have held the account for at least five years, but you'll pay tax and a 10% penalty on earnings if you make a withdrawal before then—unless the money is used for qualified education expenses for your child or grandchild. In that case, you'll owe tax on any earnings you withdraw, but you won't pay a penalty.

Custodial accounts. Also known as UGMAs (for the Uniform Gifts to Minors Act) and UTMAs (for the Uniform Transfers to Minors Act), such accounts let you set aside money or other assets in trust for a minor child and manage those assets until the child reaches the age of majority (18 or 21 in most states). At that age, the child owns the account and can spend the money for whatever he or she wants. Even if your child spends the money on education expenses, as you intended—instead of, say, a new Porsche—custodial accounts have another drawback: In financial aid formulas, students are expected to contribute a much higher percentage of assets than parents.

Still, the accounts offer some advantages. You can open an account at a bank or brokerage firm. Custodial accounts are more flexible than 529 accounts because the funds can be used for any purpose without penalty, and you can invest wherever you like. Full-time students younger than age 24 pay no tax on the first $1,050 of unearned income and are taxed at their rate on the next $1,050. Earnings above $2,100 are taxed at the parents' marginal tax rate.

When the Bills Come Due

When it's time to pay the bills, you can use a number of sources -- financial aid, scholarships, loans and current income -- to close the gap between your savings and the cost of college.

You can fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) as early as October 1 of your student's senior year of high school. Do it as soon as possible, even if you think your family earns too much to qualify for need-based aid. The federal formula considers family size and other factors besides income and assets. Plus, many colleges require the FAFSA in order to consider your student for other aid provided by the institution—and the school's definition of financial need may surprise you. For example, Princeton University awards need-based aid to nearly 60% of students, including those from families who earn $250,000 or more.

The federal formula for financial aid looks at income and assets for both parents and students when determining how much your family can pay for college. But assets in a student’s name, such as custodial accounts, are assessed much more heavily (20% to 25%) than assets in a parent's name, such as a 529 college-savings account. Those are assessed at 5% to 5.64%, minimizing their impact on financial aid awards. Nearly 400 colleges and universities also require families to file the CSS Profile, which measures income and assets differently. For example, many colleges that use the CSS Profile consider home equity and grandparent-owned 529 plans as assets.

Money held in a grandparent-owned 529 plan isn’t counted as an asset on the FAFSA. However, when you take withdrawals to pay for your grandchild's college expenses, those distributions are treated as the child’s income on the FAFSA and will reduce the student’s financial aid award eligibility. To maximize financial aid, consider waiting until January 1 of the student’s sophomore year of college or later to make the withdrawal. That way, it won’t show up on the FAFSA as long as the student graduates on time. If the student needs the money earlier, consider switching ownership to the child's parents if that change is allowed by the state's rules.

Even families who save diligently and apply for financial aid often find there's a gap between what the school expects them to pay and what they can afford. Students can ask their school guidance office for local scholarship information and visit sites such as Scholarships.com and Fastweb.com for national lists. More than 60% of students take out student loans: Student borrowers who graduated from private colleges in 2015 racked up an average of $31,400 in student loan debt; those graduating from public colleges borrowed an average of $26,800.

Whether that debt is manageable depends on the student's career prospects. To avoid borrowing too much, aim to cap total debt at no more than the anticipated starting salary after graduation and plan to pay it off in 10 years or less. You can go to www.payscale.com to see salaries in specific fields and use the figures as a guide.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.