New Strategies for Smart Borrowing

Rising interest rates and new tax rules mean taking a different approach to how you shop for loans and manage your debt.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

A lot of financially savvy people make a distinction between good debt and bad debt. Good debt is used to finance goals that will improve your net worth—such as a home purchase, a college education or a small business. Good debt is even better if it carries a low interest rate and is tax-deductible. Bad debt is the kind you incur to buy things you can’t afford with your paycheck—the big-screen TV you put on a credit card or the Caribbean trip you paid for with your home-equity line of credit. In some people’s book, it’s a bad idea to borrow to buy any depreciating asset, including a car.

But even good debt turns bad when you overindulge, as happened in the years leading up to the financial crisis. The bursting of the housing bubble and the stock market bust forced many Americans to go on a debt diet, and in the last decade, even though credit has been historically cheap, we’ve been pretty careful borrowers. Household debt has increased since the Great Recession, but that’s largely a desirable side effect of the strong economy and a healthy relaxation in lending. Mortgage balances have been rising (although they are still way below the peak reached in 2008), and student-loan, auto-loan and credit card debt levels have also gone up.

There are a few worrisome trends: Borrowers age 60 and older now hold 22.5% of total outstanding balances for all types of loans, up from 15.9% in 2008. Older borrowers are also taking on more student-loan debt to help pay for the education of children and grandchildren. The average amount of student-loan debt owed by borrowers age 60 and older nearly doubled from 2005 to 2015, to $23,500, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Another worry: Among younger student-loan borrowers, delinquencies are rising.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

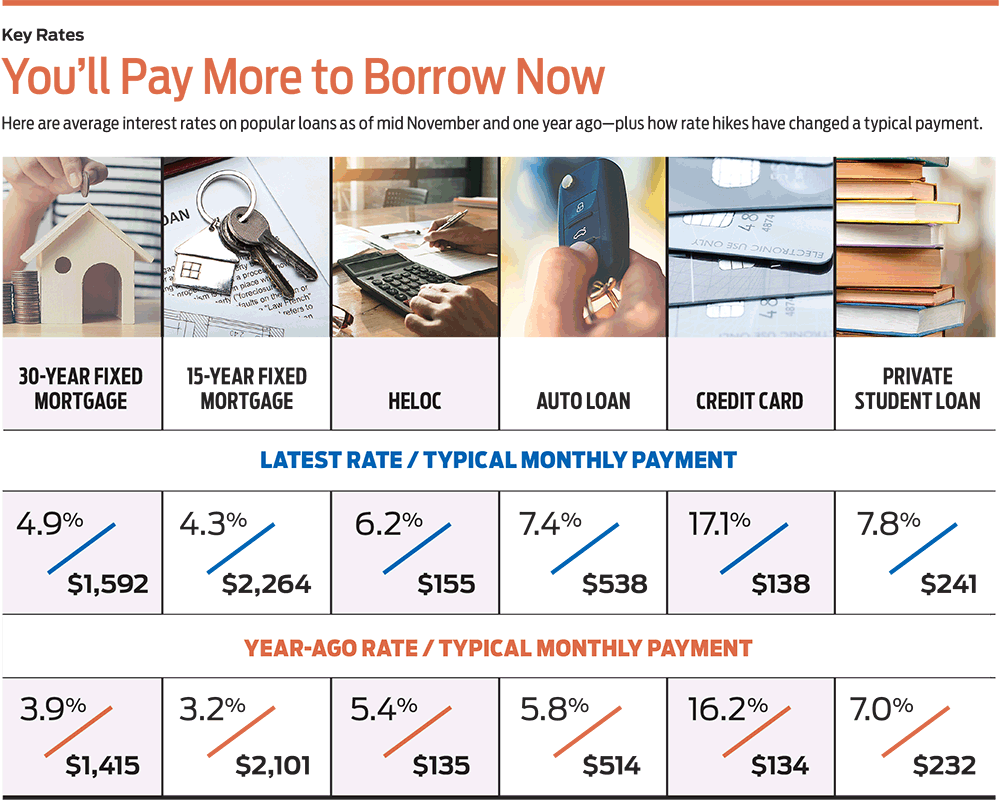

Now the days of supercheap money are coming to an end. Interest rates on consumer credit are rising, buoyed by Federal Reserve rate hikes designed to keep the economy from overheating and higher yields on long-term Treasuries. The 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose by about one percentage point in 2018, to a national average of 5%, according to Freddie Mac. The prime rate—the benchmark tied to home-equity borrowing, credit card rates and other consumer debt—also rose one percentage point in 2018, to 5.25% (as of mid November). Once plentiful 0% offers for auto loans are now scarce.

More rate hikes are coming: The Fed ratcheted up the federal funds rate by one-fourth percentage point three times in 2018 as of mid November, and Kiplinger expects an increase in December and three more increases by the end of 2019.

Rate hikes aren’t the only trend changing the borrowing equation: The new tax law puts a crimp in how much debt you can deduct. If you’re in the market for a home with a mortgage that exceeds $750,000, new limits on deducting the interest may limit how much you choose to borrow. And until 2018, you could deduct interest on up to $100,000 of a home-equity loan or line of credit—which made a HELOC a strategic way to finance a new car or college tuition or to pay off credit cards. Now the debt must be related to acquiring or improving .

Your Home

If you’re a homeowner with a fixed-rate mortgage, you don’t have to sweat rising mortgage rates. (If you are mortgage-free, congratulations.) Even so, the new tax law may upend the familiar tax-time ritual of deducting mortgage and home-equity interest, property taxes, and other state and local taxes. For many Americans, the newly doubled standard deduction will eliminate the need to itemize deductions. But if you have a high-priced home in a high-cost area—notably California, Connecticut, New Jersey or New York—you may hit a wall that prevents you from sharing the cost of homeownership with Uncle Sam. That’s because of new limits on deductions for mortgage interest as well as state and local taxes.

Strategies for homeowners. If your mortgage payments are locked in at a low rate and you’re still saving for retirement or college or have other compelling needs for your income, you probably want to let your mortgage ride, even if you will no longer deduct the interest. But if you are approaching or in retirement and being mortgage-free improves your cash flow and gives you a psychological lift, you may want to pay it off.

First, consider your whole financial picture, says Lyle Benson, a certified financial planner in Towson, Md. Do you have high-cost credit card debt? Do you need to put more money in an emergency fund? Are you still funding your children’s or grandchildren’s education? Will your adult children and aging parents need your support? If the answer to those questions is no and you have savings you could use to pay off the loan, compare the return you could get from investing the money with the after-tax cost of the mortgage. After taxes and inflation, the long-term return from investing may not be much higher than the “return” you get from paying off your mortgage. At that point, the decision hinges on your comfort level.

Short of paying off the mortgage in one fell swoop, you could accelerate payments so you retire the loan faster. Even if you already have a low rate on your mortgage, you may still come out ahead if you refinance to a shorter term of 15 or 20 years before rates go much higher. Your monthly payments will increase, but you’ll build equity more quickly, retire the mortgage earlier and pay less in total interest. Or you could prepay your mortgage. Ask your lender if it offers a biweekly mortgage payment program in which you can enroll free. If not, just make a 13th mortgage payment annually, which is the equivalent of paying half of your monthly mortgage payment every two weeks. Or simply add principal to each monthly payment.

If you have a home-equity line of credit, it’s probably tied to the prime rate, and each Fed hike boosts your rate. After the draw phase of the HELOC—usually the first five or 10 years—you’ll begin repaying principal as well as interest. But you can make principal-and-interest payments at any time during the draw phase. Alternatively, most HELOCs allow you to “lock” a portion of the line with a fixed rate and term. Lenders typically set a minimum amount for a lock and limit the number of locks.

Even if the interest isn’t deductible, home-equity borrowing is often one of the cheapest sources of credit. If you have a HELOC in the draw phase but you’re not using it, you may want to keep it open, just in case an emergency pops up. But if you can’t make any more withdrawals because you’ve tapped out your line or entered the repayment phase, consider paying off the entire balance.

Strategies for home buyers. If you’re in the market for a new home—perhaps you’re trading up—even if you aren’t in a high-cost area, you’ll encounter higher mortgage rates that have been pushing payments higher and perhaps limiting how much house you can afford.

The prospect of higher rates persuaded Adam P. Smith and his wife, Elizabeth, to move quickly to trade their family home of 16 years for a larger one with more space for their family, including Asher, 3, Alex, 14, and (when she visits) Lisa, 23. Smith, a Denver mortgage broker, was in a good position to navigate both rising mortgage rates and the overheated Denver housing market.

The Smiths sold their three-bedroom, 2.5-bath home for $480,000 and bought a five-bedroom, 3.5-bath home for $555,000. With the $240,000 they took from the home sale, they could have put down nearly half of the purchase price, but they had a different strategy: They committed just 3.5% to the down payment and locked in a 30-year fixed rate of 3.875% on a Federal Housing Administration loan. They used their remaining equity to pay off other, higher-cost debt and beef up their retirement accounts.

Smith says he’s aware that if he had put down 20% or more, he would have qualified for an even better interest rate on a non-FHA loan (and eliminated the FHA loan’s up-front and monthly mortgage insurance premium). But he believes he’s getting a better overall return by paying off debt and investing the rest. Smith doesn’t know yet whether he will take the new $24,000 standard deduction or itemize deductions. It may be a wash: The interest for the first full year in the new home will be about $21,000 and the property taxes will be about $3,100.

As homes have become less affordable and interest rates have ticked up, mortgage borrowing has slowed down, says Guy Cecala, publisher of Inside Mortgage Finance. To compete for fewer borrowers, lenders have loosened their underwriting requirements, allowing smaller down payments (as little as 3%) and higher debt-to-income ratios. For example, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will allow the total of all monthly debt payments to reach 45% to 50% of your before-tax monthly income with compensating factors, such as a big down payment, a stellar credit score and plenty of assets.

For most home buyers, it makes sense to make at least a 20% down payment to avoid private mortgage insurance. With a larger down payment, you may qualify for a lower interest rate, too. To ensure that your rate doesn’t rise before you close, ask the lender to lock the rate for 45 days. If it wants your business, it should do it free, says Mat Ishbia, president of United Wholesale Mortgage.

Student Loans

For students who borrow to attend college, the average debt at graduation is $28,500, according to the College Board. That doesn’t sound all that onerous—until you consider how much the payments on that debt limit the financial opportunities of millennials trying to save for retirement, a home and perhaps a new car. A student who graduates with this amount of debt and pays it back over 10 years at an interest rate of 5% is on the hook for payments of $302 a month; including interest, the total comes to $36,274.

You can consolidate federal (but not private) loans to combine them into one new loan (go to studentaid.ed.gov). But the interest rate of this new loan will be the weighted average of the interest rates of the debts you combine, meaning you won’t save money on interest. If you go this route, consider excluding your highest-rate loan and targeting that one for early repayment.

To lower your rate, you’ll have to turn to a private lender. That’s what Teresa Ruiz Decker, a communications consultant in Santa Cruz, Calif., did. Decker used federal loans to help fund her undergraduate degree in communications at Cal Poly Pomona, graduating with about $14,000 in debt. Then she earned a two-year master’s degree in communication management at the University of Southern California, taking on another $40,000 in federal loans. After graduate school, she combined all of her loans into one direct consolidation loan. But she grew concerned when she realized that at least two-thirds of her monthly payments were going toward interest, and she was barely making a dent in her balance, which had grown to $60,000. “It was incredible to see that I would end up paying about as much in interest as I would for my original loan,” she says. “That was my wake-up call to take action.”

Decker earned extra income through side jobs and as an Airbnb host to accelerate her payments. After her balance shrank, she refinanced her loans through CommonBond, a private lender that also supports education in developing countries. She snagged a variable rate of 3.29%, which she later converted to a fixed rate of 4.58%. Decker completed her final payment this past June. “I didn’t want to be paying off loans when I sent my own kids to college,” she says.

If you turn to private loans, note that payments on an initially low variable rate will increase as rates rise. That may make sense if you plan to pay off the loan early. But with a fixed-rate loan, the payments will be more predictable. Fixed-rate private loans from reputable lenders recently ranged from 5% to 15%, depending on the credit history and income of you or a cosigner; variable private loans hovered between 4% and 10% (and even higher) on StudentLoanHero.com, a website that offers student-loan management and repayment tools.

Also compare the term over which you’ll repay the debt. “The majority of savings are due to a shorter repayment term rather than a lower interest rate,” says Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of Savingforcollege.com. You can also shorten the repayment term by directing extra cash toward your student loans. For the graduate with $28,500 in loans, adding an extra $100 each month to payments would retire the debt nearly three years early and save $2,435. Signing up for automatic debit would cut the interest rate by 0.25 percentage point and trim $416 in interest over the life of the loan.

Notify your loan servicer that each extra payment should be credited to principal; otherwise your servicer might—and sometimes must—treat the extra money as an early payment of your next installment.

To refinance with a private lender, you will likely need a credit score of at least 700 as well as a history of on-time payments to beat the rate you currently have, says Joe DePaulo, CEO of College Ave Student Loans, a private lender. You’ll typically lose such benefits as deferment and forbearance on your federal loans if you include them in the mix. To compare options, go to Studentloanhero.com or Credible.com. Apply to multiple lenders and compare offers; the lowest advertised rates are reserved for borrowers with the strongest credit histories.

If you or your college-bound student are planning to apply for financial aid, max out federal aid first because interest rates are fixed and generally lower than fixed private loan rates. Undergraduates can take out federal loans of up to $5,500 in their first year, $6,500 in their second year and $7,500 in their third year and beyond (only a portion of those limits may be in subsidized loans). Parents can borrow through a PLUS loan up to the cost of their child’s attendance minus any financial aid the child receives. Graduate students can get up to $20,500 in unsubsidized loans per year.

Federal loans typically don’t require a cosigner and come with protections that private loans may lack, such as flexible repayment plans and postponement options. The fixed rates on federal loans reset on July 1 of each year; in 2018, the rate on undergraduate direct loans disbursed on July 1 or later rose to 5.05%, from 4.45% the previous year. Parent PLUS loans increased from 7% to 7.6%, and direct loans for graduate or professional students ticked up from 6% to 6.6%.

Auto Loans

The annual percentage rate on a new-vehicle loan in October averaged 6.2%, the highest level since January 2009, according to Edmunds, an automotive information website. Fewer than 4% of new-car sales snagged 0% finance deals in October—the lowest level since 2007.

Auto-loan terms are stretching longer as well, with five to seven years becoming more common, says Matt DeLorenzo, senior managing editor of Kelley Blue Book. Popular 72-month loans recently had an average rate of 7.4%. Longer-term loans translate into lower monthly payments but more in interest over the life of the loan.

With loan rates ticking up, you’re usually better off paying cash. But if you need to finance the vehicle, you’ll find the best deal, maybe even 0% financing, by scouring carmaker and dealership websites. Be sure to look at all incentives because a low-rate loan on one vehicle could be outweighed by a generous rebate on another, says DeLorenzo. Matt Jones, senior consumer advice editor at Edmunds, notes that manufacturers as a whole aren’t in the same rush to sell vehicles as in past years, but consumers can still find plenty of hefty rebates.

Banks and credit unions may offer competitive rates as well—as low as 2.99% from banks and 2.74% from credit unions for new cars, assuming you have a good credit score and put down at least 10%, says Bankrate—and they may match the best rate your dealer offers (but not 0%). You can also negotiate with your dealer for a lower rate by coming armed with a preapproval, or evidence of lower rates at banks or credit unions.

For a low or 0% rate, you will likely need a credit score of at least 700. If your credit is on the cusp, you might be able to qualify for a low rate as a loyal buyer of the brand or if you come up with a larger down payment.

Credit Cards

If you carry a balance on your credit cards, the interest rate is likely to bump up with each hike in the federal funds rate. The “low end” of credit card rates, or the percentage the most creditworthy customers could snag, recently averaged 17.14%, according to CreditCards.com. That’s the highest “low end” average the site has observed since it started surveying credit card rates in 2007. The “high end,” for cardholders with less than stellar credit, recently averaged 24.5%.

When you’re paying down debt, credit card balances should usually be your highest priority. One way to get credit card debt under control is to shift your balance onto a new credit card that charges no interest on transfers for a set period of time. For example, Chase Slate and BankAmericard offer a 0% rate on balance transfers and new purchases for the first 15 months, as well as no transfer fee if you move your money within 60 days of opening the account (see Stop Paying Pesky Fees). The U.S. Bank Platinum card extends its 0% balance-transfer deal to 20 months but charges a 3% transfer fee. This strategy works only if you have the discipline to pay off the balance before the interest-free term expires.

Now is a good time to apply for a balance transfer because card issuers are trimming the term for which the 0% rate applies. You can still find 0% offers with no transfer fees for as long as 15 months, says Ted Rossman, industry analyst at CreditCards.com. But he predicts that after a few more Fed rate hikes, the best no-interest, no-fee balance-transfer offers will shrink to 12 months.

If you don’t qualify for a balance-transfer card or need more time to pay off your debt, try negotiating with your issuer for a lower rate. To bolster your case, mention your loyalty as a customer or competing offers that have come your way.

Or you could pay off the card with a personal loan from a bank, credit union or online lender, such as Prosper. Personal loans can start at about 5% (the best rates go to the most creditworthy customers, though 5% will be harder to find as rates rise), and rates are fixed for the life of the loan—typically two to five years, according to NerdWallet. When comparing offers, watch out for origination fees, late fees and prepayment penalties.

New Limits on Homeowners

If you closed on a mortgage on or before December 15, 2017 (or had a binding purchase contract for a home by that date and it closed by April 1, 2018), you can still deduct the interest on up to $1 million of mortgage debt. If you took a mortgage or home-equity loan or line of credit after December 15, 2017, to buy, build, improve or refinance a primary residence or second home, you can also deduct the interest on $1 million of debt. That includes debt on a home-equity loan or line of credit.

However, interest on home-equity debt, old or new, is deductible only to the extent that you used the money to buy, build or improve your home. If you used it to buy a car, pay college tuition or take a vacation, you can’t deduct the interest. If you refinanced your mortgage, cashed out some equity and didn’t fold the money back into your home, the interest on the cash-out portion of the loan isn’t deductible, either.

Deductions for any combination of state and local income, sales or property taxes—sometimes known as SALT—are now capped at $10,000. “SALT is a good acronym, as in rubbing salt into a wound,” says certified financial planner Peter Palion. Palion lives in the high-cost New York metro area, where property taxes for even modest homes often exceed $10,000.

Suppose you took a mortgage of $1 million with an interest rate of 4.5% in 2017 or before. You could have deducted nearly $54,000 in interest incurred in the first year on the entire loan amount, and in the 33% tax bracket, you would have saved about $18,000 in federal income taxes. If you took the same mortgage now, you could deduct about $30,000 in interest on $750,000 of the loan, and in the new 32% bracket, you’d save about $13,000 in taxes, or about $5,000 less than before.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you may be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute Vacation

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute VacationTravel It is possible to pull off a cheap last-minute vacation. Here are some tips to make it happen.

-

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?insurance When assessing how much life insurance you need, take a systematic approach instead of relying on rules of thumb.

-

When Does Amazon Prime Day End in October? Everything We Know, Plus the Best Deals on Samsonite, Samsung and More

When Does Amazon Prime Day End in October? Everything We Know, Plus the Best Deals on Samsonite, Samsung and MoreAmazon Prime The Amazon Prime Big Deal Days sale ends soon. Here are the key details you need to know, plus some of our favorite deals members can shop before it's over.

-

How to Shop for Life Insurance in 3 Easy Steps

How to Shop for Life Insurance in 3 Easy Stepsinsurance Shopping for life insurance? You may be able to estimate how much you need online, but that's just the start of your search.