Drug Price Info Is No Cure for Sticker Shock

Efforts to curb spending raise questions about just how competitive health care can be.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

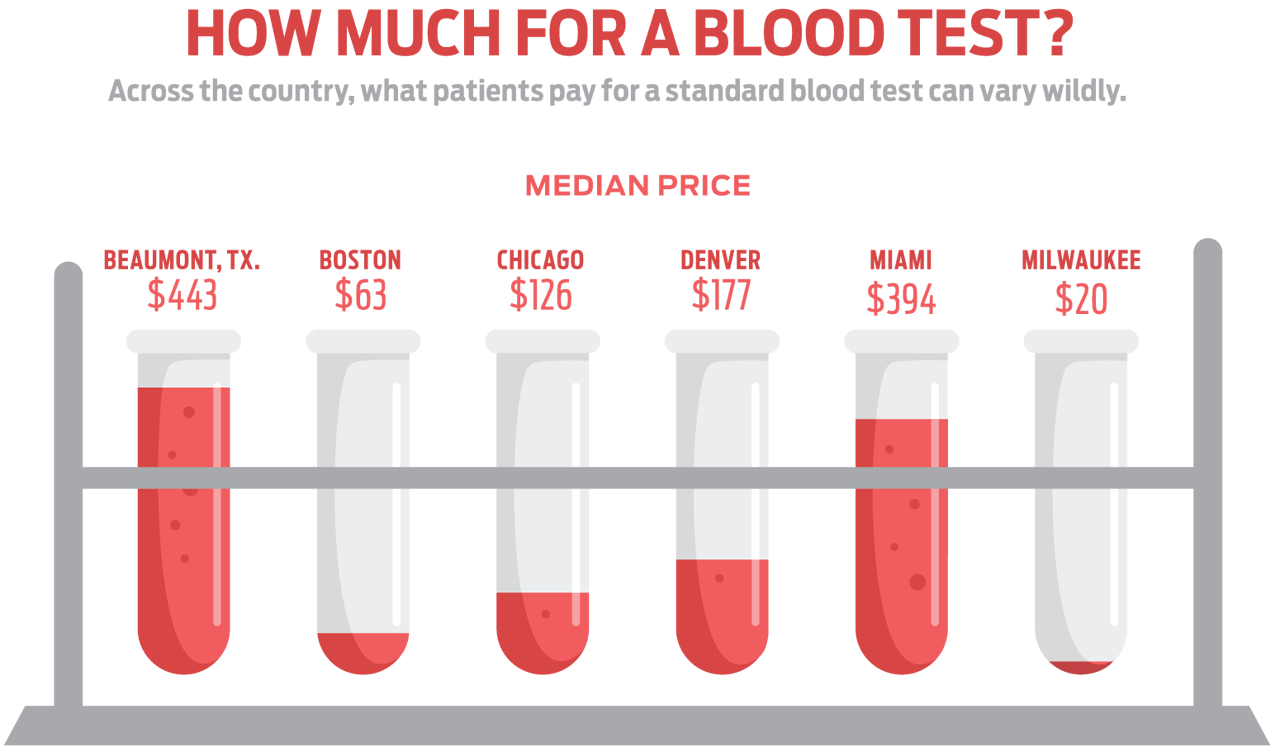

Chances are you’ve weighed a trip to the doctor based on how poorly you feel as well as how much you will pay the provider. But good luck comparison-shopping. The amounts paid by health insurers for identical services are shrouded in secrecy and can vary widely, even within the same state, metropolitan area or neighborhood.

Because these “contract negotiated rates” are typically the result of intense, closed-door negotiations between individual insurers and health care providers, patients rarely know how much they’ll pay for a procedure or service until after they’ve used it. And with the rise of high-deductible health insurance plans, which require consumers to pay more out of pocket, many patients are feeling the pain of steep, opaque costs.

Over the past few years, the Trump administration has tried a few different approaches to bring down health care costs, mostly centered on making the system operate more like a free market. One of the latest ideas: price transparency. An executive order issued in June says patients can make better-informed decisions if they know the price and quality of a service in advance.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Tough to implement. Supporters of the move say it will improve competition and lower prices. But industry groups representing both hospitals and insurance providers have spoken out against the order, suggesting transparency could actually raise prices.

Some industry analysts have also expressed skepticism that the executive order will radically alter the current landscape. “Most patients don’t think of health care as something you can shop around for, and there’s not much incentive when you don’t foot most of the bill directly,” says Larry Levitt, executive vice president of health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “And in areas where hospitals effectively have monopoly power or significant market leverage, seeing what their competitors are paid elsewhere could push them to ask for more—rather than shame them into asking for less.”

And in a blow to the administration’s strategy, a federal judge threw out a rule instructing drug companies to display the sticker price of their products in television ads, saying the government lacked the authority under current law.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has to figure out how to implement the president’s executive order and define “price transparency”—a process that will likely take several months. HHS could require service providers to publish their negotiated rates, along with quality-related statistics, such as mortality rates and incidences of hospital-acquired infections associated with services. Or it could adopt a less-sweeping approach that would allow hospitals to simply post the price range for a given service.

Supporters of price transparency say that still wouldn’t tell you how much care would cost under your insurance plan. “We need complete systemwide price transparency to make it work, which means full negotiated rates across all plans, all systems, in real-time,” says Cynthia Fisher, a life sciences entrepreneur and CEO who has pushed for price transparency in Washington for years. “Consumers can shop around when prices are accessible and searchable, and when consumers can shop around, we’ll see prices come down.”

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you may be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute Vacation

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute VacationTravel It is possible to pull off a cheap last-minute vacation. Here are some tips to make it happen.

-

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?insurance When assessing how much life insurance you need, take a systematic approach instead of relying on rules of thumb.

-

When Does Amazon Prime Day End in October? Everything We Know, Plus the Best Deals on Samsonite, Samsung and More

When Does Amazon Prime Day End in October? Everything We Know, Plus the Best Deals on Samsonite, Samsung and MoreAmazon Prime The Amazon Prime Big Deal Days sale ends soon. Here are the key details you need to know, plus some of our favorite deals members can shop before it's over.

-

How to Shop for Life Insurance in 3 Easy Steps

How to Shop for Life Insurance in 3 Easy Stepsinsurance Shopping for life insurance? You may be able to estimate how much you need online, but that's just the start of your search.