The Long-Term Allure of Dividends

The S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats index has returned an annualized 18.3% over the past 10 years, compared with 17.1% for the S&P 500.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

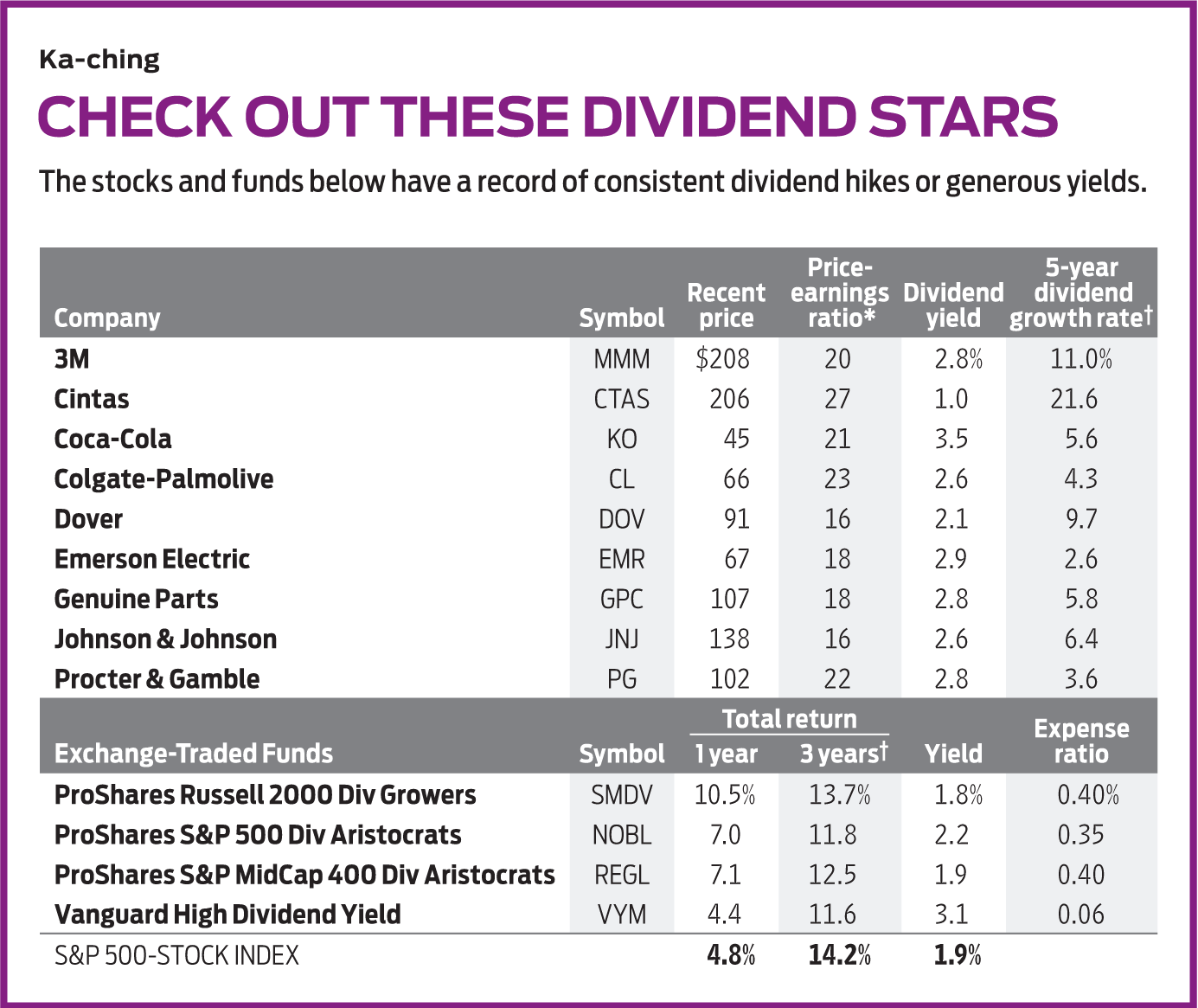

These are heady days for dividend lovers. Dozens of companies with excellent track records are providing investors with annual payouts that exceed yields on five- and even 10-year Treasury bonds. Yes, Treasuries may be safer, but dividends tend to rise over time. Plus, when your T-bond matures, you simply get back its original face value—unlike stocks, which can appreciate.

For example, the 10-year Treasury bond yields 2.59%, but Procter & Gamble (symbol PG, $102), a member of the Kiplinger Dividend 15, the list of our favorite dividend-paying stocks, yields 2.8% and has increased its dividend for 62 consecutive years. Coca-Cola (KO, $45), which said in February that it was raising its dividend for the 55th year in a row, is yielding 3.5%. (Prices and returns are through March 15.)

But are dividend-paying stocks really superior? Had you invested solely in stocks that make regular payouts to shareholders, you would have missed some of the market’s biggest successes. Alphabet, Amazon.com, Berkshire Hathaway and Facebook—four of the six largest companies by market capitalization—pay no dividends.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Rather than handing money to their shareholders every few months, fast-growing companies often invest their profits in their own business—in new factories or software, as Amazon has done in building its cloud-computing subsidiary, or buying complementary firms, as Alphabet (then called Google) did when it bought YouTube.

Warren Buffett, chairman of Berkshire, likes collecting dividends from the companies he owns, but he never pays them himself. He wrote in 2013, “Our first priority with available funds will always be to examine whether they can be intelligently deployed in our various businesses…. Our next step … is to search for acquisitions unrelated to our current businesses.”

You might consider dividend-paying a kind of failure of imagination by management. Why, then, has a particular kind of dividend-paying stock become especially popular in recent years? I’m talking about the stocks of companies, such as Procter & Gamble and Coca-Cola, that increase dividends year after year.

To increase a dividend consistently, a company typically needs a distinct competitive advantage, a “moat” that keeps competitors from the gates.

At the end of 2018, there were 53 firms in Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index that met this standard for at least 25 years, qualifying for the encomium “Dividend Aristocrats.” But why laud such companies when, year after year, they return more money to investors because management can’t put it to better use?

The answer is that investing in stocks that pay dividends—especially rising dividends—turns out to be a terrific strategy. The S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats index has returned an annual average of 18.3% over the past 10 years, compared with 17.1% (including dividends) for the S&P 500 as a whole. Usually, higher returns indicate higher risk, but the Aristocrats have achieved their returns with less volatility than the full S&P.

Why do consistent dividend-raisers perform so well?

They have a moat. To increase a dividend consistently, a company typically needs a distinct competitive advantage, a “moat” that keeps competitors from the gates. A moat lets the firm raise prices and keep the profits flowing even in bad times. A good example is Coca-Cola, one of Buffett’s favorites. Its strong brand and distribution system provide one of the widest moats in the business world.

Dividends don’t lie. Dividends are probably the best indicator of the health of a business. You can manipulate earnings per share, but you can’t fake cash.

Conservative ideals. Companies that want to maintain a record of dividend hikes are run conservatively because the worst calamity for them is a dividend cut. In investing, a great way to make money is to avoid firms that take too many risks and concentrate instead on the plodding winners. Dover (DOV, $91) scores profits through a diversified business that makes such boring items as refrigerator doors and industrial pumps. The result has been 63 consecutive years of increased dividends.

They’re a buffer. Dividends provide a buffer in difficult times. In a bad year, the market may drop 3%, but if the yield on your portfolio of dividend-paying stocks is 3%, you’ll break even.

In 2008, the worst year for large-cap stocks since 1931, the S&P 500 lost 37% (counting dividends), but the Dividend Aristocrats lost only 21.9%—thanks to moats, conservative management and consistent payouts. In 2018, the S&P 500 lost 4.4%; the Dividend Aristocrats index lost 2.7%.

A good way to buy these stocks is through ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats (NOBL, $67), an exchange-traded fund (ETF) with an evenly weighted portfolio and an expense ratio of 0.35%. The fund has not only beaten the S&P 500, it has also finished in the top half of its category (large-company blend) in every one of its five full calendar years of existence. Among the stocks in the fund’s portfolio that have raised dividends for at least 55 years in a row (in addition to Coke, P&G and Dover) are 3M (MMM, $208), Colgate-Palmolive (CL, $66), Emerson Electric (EMR, $67), Genuine Parts (GPC, $107) and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ, $138). 3M, Emerson and J&J are also Kip Dividend 15 picks.

Although the Aristocrats fund has been impressive, it does not provide enough diversification all by itself. The fund is heavily weighted toward industrial and consumer-products stocks, and less than 2% of the fund is in technology—a sector that represents 20.6% of the S&P 500. And it owns only large-company stocks.

ProShares also offers a mid-cap version, ProShares S&P MidCap 400 Dividend Aristocrats (REGL, $56), with a requirement that stocks have only 15 consecutive years of rising dividends, as well as a small-cap version, ProShares Russell 2000 Dividend Growers (SMDV, $59), with a 10-year minimum. Both funds are relatively new, but both have clobbered their peers (mid-cap value and small-cap core funds) over the past three years, according to Morningstar.

Simply buying well-chosen dividend stocks is not a ticket to success. Take, for example, Vanguard Dividend Growth (VDIGX), a very popular mutual fund ($34 billion in assets) now closed to new investors. Run by a human manager and charging 0.26% in expenses, the fund returned an annual average of 15.1% over the past 10 years, compared with 16.5% for the S&P 500.

I should add that although Aristocrats keep increasing their payouts, the yields for some of them can be exceptionally low. Cintas (CTAS, $206), which rents work uniforms and has been one of my favorite stocks for decades, has raised its dividend every year since going public in 1983. Despite a big payout hike last year, its shares yield only 1%.

The average S&P 500 stock yields 1.9%, and ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats yields only a bit more. If you want higher yields with slightly added risk, the best bet is Vanguard High Dividend Yield (VYM, $86), an ETF based on an FTSE Dow Jones benchmark. With expenses of just 0.06%, it recently yielded 3.1%. Over the past 10 years, it has essentially kept pace with the S&P 500, trailing the index by an annual average of just two-tenths of a percentage point.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. Of the stocks mentioned here, he owns Amazon.com.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market TodayPalantir Technologies proves at least one publicly traded company can spend a lot of money on AI and make a lot of money on AI.

-

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market Today

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market TodayIncoming economic data, including the January jobs report, has been delayed again by another federal government shutdown.

-

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market Today

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market TodayA "long-overdue correction" temporarily halted a massive rally in gold and silver, while the Dow took a hit from negative reactions to blue-chip earnings.

-

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market TodayMicrosoft, Meta Platforms and a mid-cap energy stock have a lot to say about the state of the AI revolution today.

-

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will probably have to wait until after Jerome Powell steps down for the next Fed rate cut.

-

S&P 500 Hits New High Before Big Tech Earnings, Fed: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Hits New High Before Big Tech Earnings, Fed: Stock Market TodayThe tech-heavy Nasdaq also shone in Tuesday's session, while UnitedHealth dragged on the blue-chip Dow Jones Industrial Average.

-

Dow Rises 313 Points to Begin a Big Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Rises 313 Points to Begin a Big Week: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 is within 50 points of crossing 7,000 for the first time, and Papa Dow is lurking just below its own new all-time high.