Take a Flier on a Friend?

Great things can happen when you help start a company. So can total failure.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

The next time you're in a Wal-Mart, consider how the retailing world would look today had Sam Walton's father-in-law not bankrolled his first store. Imagine the recording business had Ahmet Ertegun's dentist refused to make a $10,000 investment to launch Atlantic Records. And credit Leslie Wexner's aunt for the seed money that funded the small women's apparel shop that morphed into The Limited.

There is no question that money from friends and family is the lifeblood of entrepreneurial ventures. Such informal investing provides more than $100 billion -- nearly 1% of the gross domestic product -- to some three million start-ups each year. By contrast, venture capitalists supply $25 billion a year -- and rarely to businesses in the earliest stages. The typical loan or donation (or a combination of both) from friends and family runs $20,000 to $25,000 per contributor. It's no coincidence that 58% of businesses on a recent list of the fastest-growing companies in the U.S. started with $20,000 or less.

Given the rich lore of killings made by those who got in on the ground floor, it's tempting to invest in a friend or relative who pitches an intriguing idea. Go ahead, we won't stop you. Just make sure you're motivated more by altruism than by avarice because, despite a handful of high-profile successes, chances are you won't make a killing or get your money back in a timely fashion -- and in some cases, you won't get it back at all. But you can give a loved one a leg up, contribute to the economy and give a project you believe in a chance to succeed. And if you do it all in a sensible way, you might come out ahead, or at least minimize the fallout and keep Thanksgiving a pleasant occasion.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

A winning bet

Success can sometimes seem downright arbitrary. Mike Andrews, 62, invested in a high-tech venture in the late '90s put together by his son Scott, Scott's childhood buddy Peyton Anderson and a couple of their friends. The company sold scientific equipment and materials over the Internet. Andrews had coached the boys' Little League team and recalls Anderson saving a playoff game with a diving catch. "I know nothing about technology. I invested 100% because of Peyton and my son," Andrews says.

He put "tens of thousands" of dollars into shares of SciQuest, both before and after it became a hot new stock in the high-tech bubble days. Because of stock-sale restrictions on early investors, Andrews could sell only 7% to 8% of his holdings before the bubble burst and shares of SciQuest collapsed. Even so, he earned back what he put in many times over. Andrews is now an investor in Anderson's new venture, a biotech firm called Affinergy.

[page break]

It's so hard to get start-up investing right that even savvy venture capitalists' annual returns average only in the mid teens. Studies show that half of informal investors -- friends, family, neighbors, co-workers and the like -- expect just to break even or to lose money, says William Bygrave, professor of entrepreneurship at Babson College, in Wellesley, Mass. Although there is little evidence of how much is actually earned or lost, we've all heard the sorry statistics: A study by Bureau of Labor Statistics economist Amy Knaup found that one-third of small businesses fail after two years and over half after four. "You are not being gouged," says Bygrave, "if you go in with your eyes wide open."

What should you look for if a friend or family member hits you up for cash? First, check to see if the person has expertise in the business in question or has the ability to attract someone who does. "It's like a lawyer trying to open up an ice cream shop," says Phil Bronner, a venture capitalist who specializes in early-stage start-ups for Bethesda, Md.-based Novak Biddle Venture Partners. "It's hard to believe that a person competent in one domain can apply that knowledge in another. You don't want just a smart person. You want real expertise."

Take, for example, the investment that Michael Smith, 53, made in the gymnastics studio his daughter's coach wanted to open in a Dallas suburb. The original owner had moved the studio from rented gym to rented gym, and the coach approached a number of families with a plan for a better-run operation. He'd scouted locations in a fast-growing Dallas suburb and had carefully calculated the cost of renting a facility, converting it into a gym, buying equipment, signing up kids and hiring coaches.

But most tellingly, among the coach's investors were several with relevant business backgrounds, including a chief financial officer for a local firm. The coach "had a good, solid business plan and the right guys surrounding him to make it work," says Smith. The investors, who collectively put up $200,000 about five years ago, got seats on the board of the new enterprise, which is thriving today. Smith got his $60,000 loan repaid, plus $18,000 in interest.

Customers are key

You should expect to hear about customers, not just concepts. "Entrepreneurship is all about implementation," says Bygrave. "Those who succeed are better implementers." He encounters two types of would-be entrepreneurs in his classes. Some are conceptual: They bury themselves in research, polishing a business plan and selling it to investors. But the ones who are usually most successful are those who can't wait to start finding customers. If someone tells you he's invented a new toothbrush, for example, ask if he can name any customers. Wrong answer: "Why, everyone who cleans his teeth!" Better: "I'm meeting with the toothbrush buyers from CVS and Wal-Mart."

It may sound strange, but ask yourself if you're being hit up for enough money. "If someone is asking for $5,000, but it's going to take half a million to get the enterprise going, then you've got a financing risk," says Bronner. "They may not be raising enough money to give it a college try."

In that case, you are likely to face one of three scenarios. The business could run out of money and close. The owner might approach you for more money. Or the earliest investors unwittingly prime the pump for later, outside investors -- who typically extract better terms. "The last money in wins," says Peyton Anderson. "Friends and family can get burned in spite of the best intentions." The best way to prevent hard feelings is for owners to be honest about their intentions, and for friends and family to be realistic about their place in the entrepreneurial food chain.

Make sure your money is supporting the business, not your relative's lifestyle. Are salaries in line with the company's stage of development? While you're at it, be picky about how the business is structured. Businesses that are incorporated have a higher survival rate -- 40% to 50% of them survive at least ten years, Bygrave has found. Any legal structure that separates the business from the personal affairs of the founder will do the trick, including a Subchapter S corporation, a limited partnership or a limited liability corporation.

Above all, make sure you invest only money you can afford to lose. Michael Smith cashed out some stock options in the semiconductor company he worked for at the time to invest in the studio -- at a fortuitous time, it turns out. "Those options were worth something then," says Smith, who was cautioned by his financial adviser to "kiss that money goodbye" when he turned it over to the entrepreneurial coach.

[page break]

Put it in writing

As realistic as your expectations may be, you'll still want to formalize an equity investment or a loan as if you're counting on a return. It goes without saying that you should put your agreement in writing. You might even want to engage a third party to dot i's, cross t's and keep everyone on schedule. CircleLending (800-805-2472; www.circlelending.com), a specialty loan administration company in Waltham, Mass., manages loans among relatives, friends and other private parties. The company says it has customers in all 50 states and a loan portfolio of $150 million that it oversees. "People use us when they want a third party with no ax to grind," says vice-president Jim Smith. "That way they don't have to talk about the business at dinner or when they see each other on the weekend."

CircleLending doesn't lend money; it just services the loans. For $199, the company will structure an unsecured note; for $299, it will put together a legal contract secured by collateral, such as a piece of property or equipment. For $9 per transaction, the company will service the loan, debiting one account and crediting the other. It also sends year-end statements to both parties for record-keeping and tax purposes. (For more on structuring an agreement, see the list below.)

In the event that your investment turns sour, explore ways to squeeze lemonade out of lemons. If you sell your equity stake for less than you paid for it or if your equity is wiped out, you can claim a capital loss, using it to offset capital gains and up to $3,000 a year of other income. Passive losses -- money you lost in a business in which you didn't work -- can be used to offset income from other similarly passive investments. If you actively participated in the business, spending at least half your time there, you can use losses to offset any income.

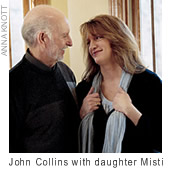

Bloomington financial planner David Hays devised a clever way for Collins, the pizza-parlor investor, to make use of his substantial losses. Because Collins qualified as an active participant in his daughter's pizza joint, he was able to use his losses to offset income and gains earned elsewhere. Collins used the losses to offset income he generated when he converted money in a traditional individual retirement account to a Roth IRA. (Because money goes into a regular IRA tax-free, it's usually taxed when converted to a Roth. Money can be withdrawn from a Roth tax-free.) Collins wound up converting $132,000 tax-free -- enough lemonade to make his losses, no matter how disappointing, a little less sour.

Improving your odds

Don't take a flier on a friend or relative unless you have a realistic repayment plan. Whether you let a lawyer or another third party help you structure an agreement, a businesslike arrangement is crucial. Here's what to consider:

The term of the loan, the payment amount, the payment schedule and the interest rate.

How to handle early repayments, which might cut into your expected return.

How to handle late or missed payments. A missed payment might be spread out over several months or added on at the end of the term.

How, when and to what extent a loan will be repaid if the business fails.

The percentage of ownership you're entitled to if you invest equity. You may ask, for example, why investors are putting up 80% of the money but getting only 20% of the equity.

Voting rights, if any, to which you are entitled.

Special arrangements. You might choose interest-only payments for the first year or two, or forgo payments entirely for a period. If the latter, will interest accrue during that time? You might get paid on a seasonal basis for some businesses, such as an ice cream parlor at the beach.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Anne Kates Smith brings Wall Street to Main Street, with decades of experience covering investments and personal finance for real people trying to navigate fast-changing markets, preserve financial security or plan for the future. She oversees the magazine's investing coverage, authors Kiplinger’s biannual stock-market outlooks and writes the "Your Mind and Your Money" column, a take on behavioral finance and how investors can get out of their own way. Smith began her journalism career as a writer and columnist for USA Today. Prior to joining Kiplinger, she was a senior editor at U.S. News & World Report and a contributing columnist for TheStreet. Smith is a graduate of St. John's College in Annapolis, Md., the third-oldest college in America.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second Term

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second TermSix months after President Donald Trump's inauguration, take a look at how the stock market has performed.

-

What the Rich Know About Investing That You Don't

What the Rich Know About Investing That You Don'tPeople like Warren Buffett become people like Warren Buffett by following basic rules and being disciplined. Here's how to accumulate real wealth.

-

How to Invest for Rising Data Integrity Risk

How to Invest for Rising Data Integrity RiskAmid a broad assault on venerable institutions, President Trump has targeted agencies responsible for data critical to markets. How should investors respond?

-

What Tariffs Mean for Your Sector Exposure

What Tariffs Mean for Your Sector ExposureNew, higher and changing tariffs will ripple through the economy and into share prices for many quarters to come.

-

How to Invest for Fall Rate Cuts by the Fed

How to Invest for Fall Rate Cuts by the FedThe probability the Fed cuts interest rates by 25 basis points in October is now greater than 90%.

-

Are Buffett and Berkshire About to Bail on Kraft Heinz Stock?

Are Buffett and Berkshire About to Bail on Kraft Heinz Stock?Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway own a lot of Kraft Heinz stock, so what happens when they decide to sell KHC?

-

How the Stock Market Performed in the First 6 Months of Trump's Second Term

How the Stock Market Performed in the First 6 Months of Trump's Second TermSix months after President Donald Trump's inauguration, take a look at how the stock market has performed.

-

Fed Leaves Rates Unchanged: What the Experts Are Saying

Fed Leaves Rates Unchanged: What the Experts Are SayingFederal Reserve As widely expected, the Federal Open Market Committee took a 'wait-and-see' approach toward borrowing costs.