What You Need to Know About Stock Markets Today

Thanks to electronic trading, the stock market is wilder than ever.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Editor's Note: We are re-featuring this guide to understanding the markets in light of the announcement on February 15 that the parent company of the New York Stock Exchange has agreed to merge with Deutsche Boerse. The merger would create the world’s largest operator of financial markets. Deutsche Boerse shareholders would own 60% of the merged company; NYSE Euronext shareholders, 40%. The text below has been updated since publication in the October 2010 issue of Kiplinger’s Personal Finance and the data is as of February 16, 2011.

1. There's no "there" there. You may picture a bustling exchange, where commerce begins and ends with the clang of a bell. But the "stock market" is an increasingly fragmented collection of more than 50 trading platforms, almost all electronic, with various protocols, rules and oversight.

2. The Big Board has shrunk. Images of the New York Stock Exchange still dominate business-news broadcasts. But, in fact, just 34% of the trading volume in stocks listed on the NYSE actually occurs on the exchange, down from 79% in 2005. Nasdaq, the first electronic exchange, accounts for about one-fifth of all U.S. stock trading. Newer exchanges, such as Direct Edge, in Jersey City, N.J., and BATS Exchange, in Kansas City, Mo., each account for about 10% of trading volume. About 30% of U.S. trading volume takes place off exchanges.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

3. ECNs are the new matchmakers. Electronic communication networks match up buy and sell orders at specified prices for institutional investors and brokers. This is where "after-hours" trading occurs. In addition, hundreds of broker-dealers execute trades internally, filling orders out of their own inventory.

4. Some trades are shrouded in mystery. You've heard of dark stars. Now there are dark pools -- private networks, sponsored by securities firms, where professionals trade without displaying price quotes to the public beforehand. Such dark pools account for more than 10% of stock-trading volume. The Securities and Exchange Commission wants to make dark pools more transparent to avoid a two-tier market that denies the public important pricing information.

5. You're sure to get the best price -- most days. According to an SEC rule, your trade is supposed to be routed to the platform with the best price at that moment. But when some venues aren't functioning as normal, exchanges may override the rule. The rule didn't apply during the "flash crash" of May 2010, when an intentional slowdown on the NYSE caused orders to be routed elsewhere, at lower prices.

6. There are fewer traffic cops. In the old days, specialists and market makers kept markets liquid by stepping up to buy -- or sell -- when a stampede of investors headed the other way. Now, not all exchanges require market makers. High-frequency traders, who program computers to profit from minute price discrepancies and can execute trades in milliseconds, were supposed to fill the void. But they don't have to, despite the fact that they often account for 50% or more of total trading volume.

7. Stoplights are coming. A pilot plan, recently extended until April, calls for stock-by-stock circuit breakers that would be applicable across all trading platforms. The plan currently applies to stocks in Standard & Poor's 500-stock index, the Russell 1000 index and certain exchange-traded funds, and calls for a trading pause if the share price changes by 10% within a five-minute period. Since December, market makers in exchange-listed securities have been required to maintain continuous buy and sell quotes within a certain range of a security's most recent share price, putting an end to occasionally ridiculous quotes, far removed from prevailing prices, that were never meant to be executed.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Anne Kates Smith brings Wall Street to Main Street, with decades of experience covering investments and personal finance for real people trying to navigate fast-changing markets, preserve financial security or plan for the future. She oversees the magazine's investing coverage, authors Kiplinger’s biannual stock-market outlooks and writes the "Your Mind and Your Money" column, a take on behavioral finance and how investors can get out of their own way. Smith began her journalism career as a writer and columnist for USA Today. Prior to joining Kiplinger, she was a senior editor at U.S. News & World Report and a contributing columnist for TheStreet. Smith is a graduate of St. John's College in Annapolis, Md., the third-oldest college in America.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

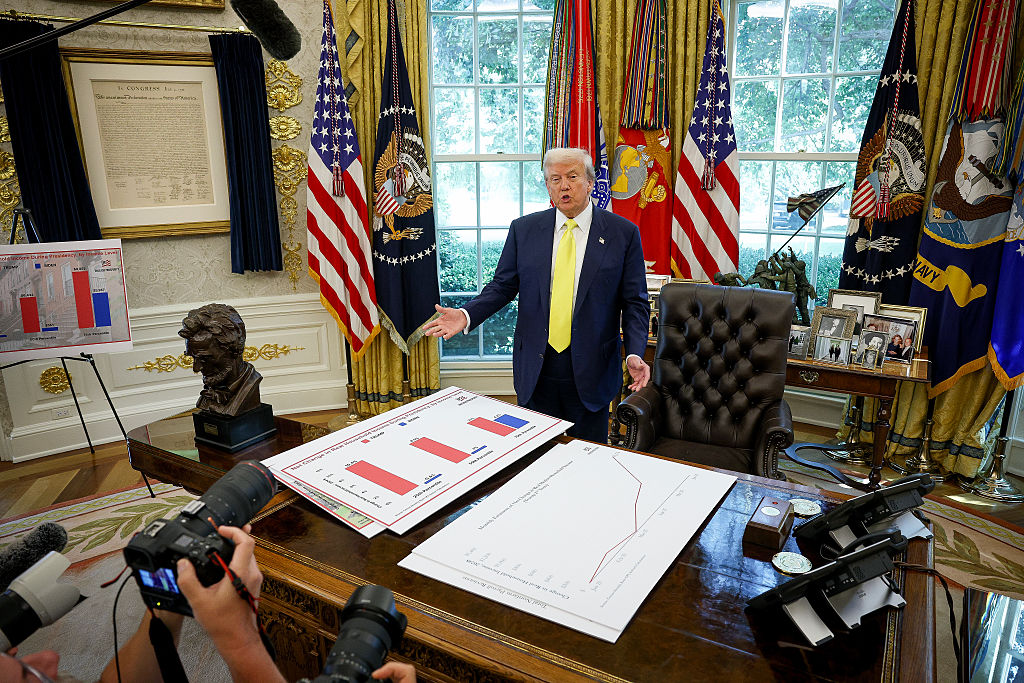

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second Term

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second TermSix months after President Donald Trump's inauguration, take a look at how the stock market has performed.

-

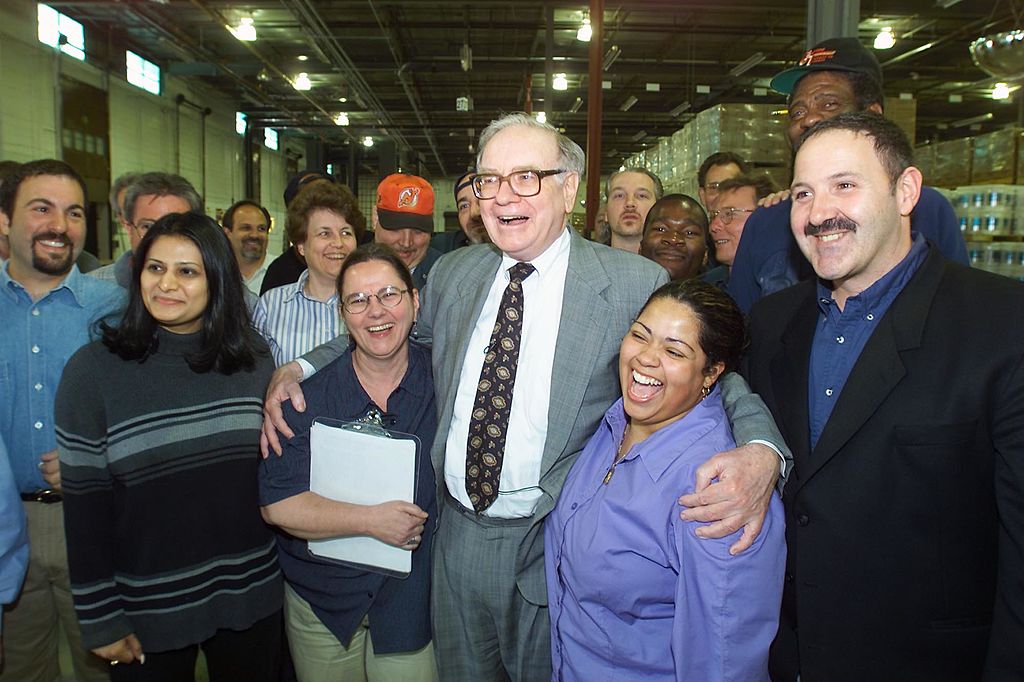

What the Rich Know About Investing That You Don't

What the Rich Know About Investing That You Don'tPeople like Warren Buffett become people like Warren Buffett by following basic rules and being disciplined. Here's how to accumulate real wealth.

-

How to Invest for Rising Data Integrity Risk

How to Invest for Rising Data Integrity RiskAmid a broad assault on venerable institutions, President Trump has targeted agencies responsible for data critical to markets. How should investors respond?

-

What Tariffs Mean for Your Sector Exposure

What Tariffs Mean for Your Sector ExposureNew, higher and changing tariffs will ripple through the economy and into share prices for many quarters to come.

-

How to Invest for Fall Rate Cuts by the Fed

How to Invest for Fall Rate Cuts by the FedThe probability the Fed cuts interest rates by 25 basis points in October is now greater than 90%.

-

Are Buffett and Berkshire About to Bail on Kraft Heinz Stock?

Are Buffett and Berkshire About to Bail on Kraft Heinz Stock?Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway own a lot of Kraft Heinz stock, so what happens when they decide to sell KHC?

-

How the Stock Market Performed in the First 6 Months of Trump's Second Term

How the Stock Market Performed in the First 6 Months of Trump's Second TermSix months after President Donald Trump's inauguration, take a look at how the stock market has performed.

-

Fed Leaves Rates Unchanged: What the Experts Are Saying

Fed Leaves Rates Unchanged: What the Experts Are SayingFederal Reserve As widely expected, the Federal Open Market Committee took a 'wait-and-see' approach toward borrowing costs.