What Should Investors Do Now?

Here are answers to 12 pressing questions about the current financial turmoil.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Is now a good time to buy stocks? What's the market's long-term outlook? How can I be ultra-safe? After two weeks of market upheaval and political tension, Manny Schiffres, executive editor of Kiplinger's Personal Finance, answers the questions that are top-of-mind for investors.

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | 10 Things That Will Change |

| Row 1 - Cell 0 | 15 Things to Know About the Panic of 2008 |

| Row 2 - Cell 0 | How to Cope With the Financial Crisis |

1. Okay, Congress finally approved the $700-billion financial-company rescue package October 3 after initially rejecting it. Does this mean the worst is over for the stock market?

Answer: The deal does one important thing very well: It buys time -- time for the financial community to try to deleverage itself. Investment banks in particular, but also many commercial banks and other financial institutions, lent far too much money without considering the things that could go wrong (see 15 Things to Know About the Panic of 2008). The rescue plan engineered by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and congressional leaders will buy up to $700 billion of those unsellable securities.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

What nobody can predict is whether this plan will perform the three desired miracles: Reassure investors that it's safe to invest in stocks again, persuade bankers that it's safe to lend money again and comfort consumers that it's safe to spend again. As events play out, other imaginative moves may prove necessary. But whatever the outcome, it beats doing nothing. This much is certain: The value of a Harvard Business School degree is already a lot less than it used to be.

2. What are the major concerns?

Whether so much government borrowing (on top of Uncle Sam's already massive debt load) will lead to significantly higher interest rates. And whether $700 billion will be enough to cover the bad debts lurking in bank and brokerage-company portfolios.

As for the economy, dismal reports released on September 25 on durable goods, jobless claims and new-home prices underscore its weakness -- and a turnaround isn't anywhere in sight. That's mainly because the freeze-up in the credit markets is making it hard for individuals and businesses to borrow. And as Citigroup strategist Tobias Levkovich points out, there is typically a lag of about nine months between credit availability and its impact on such things as industrial activity, capital spending and employment trends. Levkovich says we should "expect more challenging economic data in coming months."

3. Are you saying we should be selling stocks or, at least, not adding to our stock holdings until the economy starts to turn?

It might be prudent to wait a few months before stocking up. The problem with basing investment decisions on economic conditions is that bull markets always begin several months before the economy hits bottom and, typically, when the news is bleakest. Given continuing woes in the business credit markets, odds are tilting strongly towards a recession this winter. Stocks will be poor-to-lackluster performers for at least several more months.

4. What about mutual funds?

Funds are investment vehicles. They're as safe, or as risky, as the securities in which they invest. Of the major asset categories, stock funds are the riskiest, bond funds range from fairly risky to low risk, and money-market funds carry the lowest risk.

5. Should I be worried about the fact that a money-market fund recently "broke the buck?"

No. The government has unveiled a temporary program to insure assets in money funds as of September 19, 2008 (see Is My Money-Market Fund Still Safe? and Money-Market Funds: Now a Safer Haven). If you want to play it extra-safe, invest only in money funds sponsored by large companies, such as Fidelity and T. Rowe Price, that have the wherewithal to bail out their funds should any of them threaten to break the buck.

6. So, what should I be doing now?

First, keep in mind John Kenneth Galbraith's famous line: "There are two kinds of forecasters: Those who don't know, and those who don't know they don't know." Because few of us can predict the fluctuations of the markets, it's best to stick with things we can control.

For starters, a bear market is always a good time to take a hard look at your portfolio and gauge how much risk you can stand. From their peak last October 9, U.S. stocks, as measured by Standard & Poor's 500-stock index, have dropped by more than 20% (many individual stocks have, of course, dropped far more and some financials -- think Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual -- have been wiped out). If a decline of that magnitude doesn't faze you, stick with your plan. If it leaves you queasy, you probably need to trim your allotment to stocks and add to your bond and cash holdings.

7. I invest regularly in my employer's 401(k) plan and put the bulk of my money into stock funds. Should I stick with the program?

Absolutely. If you stop investing in your retirement plan or you terminate any kind of a dollar-cost-averaging program, you're defeating one of the major purposes of systematic investing: It forces you to keep buying stocks when their prices are falling and they're on sale. That's something you probably wouldn't do if you were left to your own devices. If you're worried about the investments in your 401(k) plan, it's better to tinker with the breakdown among stocks, bonds and cash rather than to stop your regular-investment program.

8. Should I rebalance my portfolio?

Probably. Like dollar-cost-averaging, regular rebalancing is designed to take the emotion out of decision-making. It forces you to sell the investments that have been performing relatively well and to shift the proceeds into the relative laggards.

If a year ago you placed $7,000 in a stock fund and $3,000 in a bond fund, chances are that the former is now worth about $5,600 and the latter is worth about $3,100. To restore the 70%-30% split, you'll have to transfer about $500 from the bond fund to the stock fund. Such a move might not pay off over the short term, but it almost certainly will over the long haul.

9. What do we need for a new bull market in stocks to begin?

Probably the single most bullish factor would be signs that the housing market is bottoming. Falling housing prices and the credit crisis are intimately connected. Stabilization of housing prices, particularly in those states hardest hit by falling prices (California, Florida, Arizona and Nevada), would attract home buyers and improve consumer sentiment, and it could lead to higher values for many of the battered mortgage securities that the government plans to buy from troubled banks.

10. Are stocks still the best investment for the long haul?

Yes. For starters, most of the key alternatives aren't terribly appealing. The average taxable money-market fund yields 2.2%. If you buy a ten-year Treasury note and hold it to maturity, you'll earn about 3.8% per year. You could invest in a junk-bond fund that yields 9% or so, but that comes with its own set of risks.

Don't bet on stocks earning the historical return of 10% annualized over the next ten years. The reason: The economy and, hence, corporate earnings will grow at a below-average rate as the U.S. -- individuals, businesses and the government -- unwinds from its debt binge. On the plus side, stocks aren't terribly expensive -- nor should they be, coming off a ten-year period during which the S&P 500 returned only 3% annualized. In fact, between March 24, 2000, when the technology-driven bull market peaked, and September 25, the index lost an annualized 1%. Stocks are due for a period of decent, if not scintillating, performance.

11. What's the best I can do if I can't handle any risk whatsoever?

The typical taxable money-market fund yields about 2.2% today. That's nothing to write home about, especially if the money is in a taxable account. But some bank money-market accounts are yielding more than 3.5% (see www.bankrate.com for top yielders). And because of upheaval in the market for short-term municipal IOUs, tax-free money-market funds are currently delivering extraordinary returns. The average tax-free money fund yielded 4.19% as of September 25, according to Crane Data. As of September 26, Fidelity Municipal Money Market Fund (symbol FTEXX) sported an effective seven-day yield of 5.33%.

12. Are there any investing layups out there?

See the preceding answer. A 5.35% tax-free yield is the equivalent of 8.2% for a taxpayer in the 35% bracket. Those outsize tax-free money-fund yields aren't likely to last long, so take advantage of them while you can.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

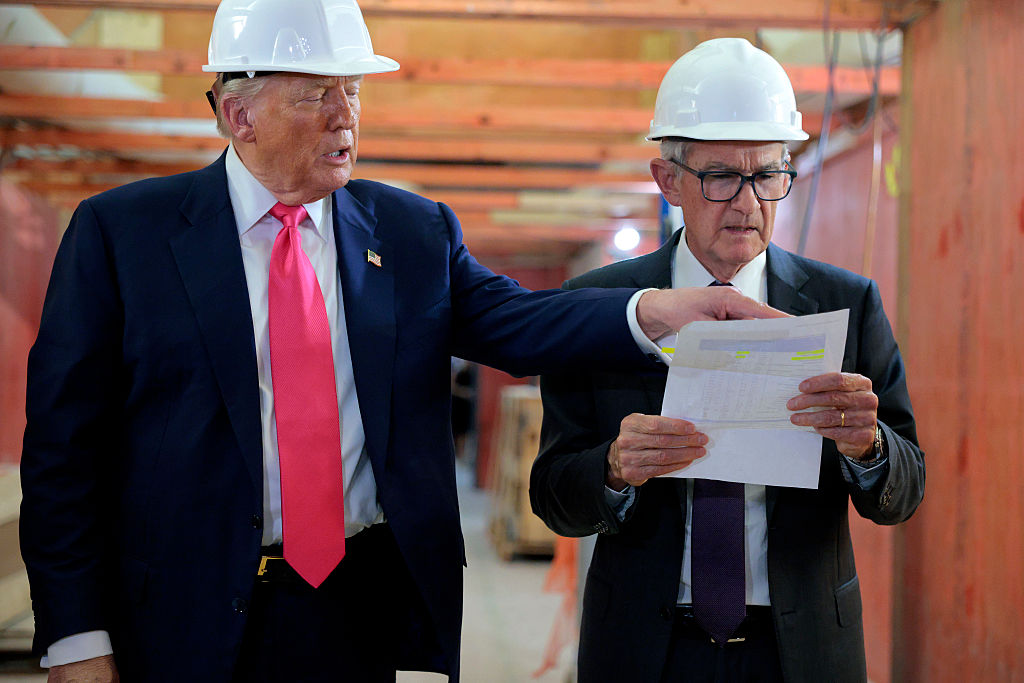

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into AMD Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into AMD Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayAdvanced Micro Devices stock is soaring thanks to AI, but as a buy-and-hold bet, it's been a market laggard.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into UPS Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into UPS Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayUnited Parcel Service stock has been a massive long-term laggard.

-

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second Term

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second TermSix months after President Donald Trump's inauguration, take a look at how the stock market has performed.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.