Why the Strong U.S. Dollar Scares Investors

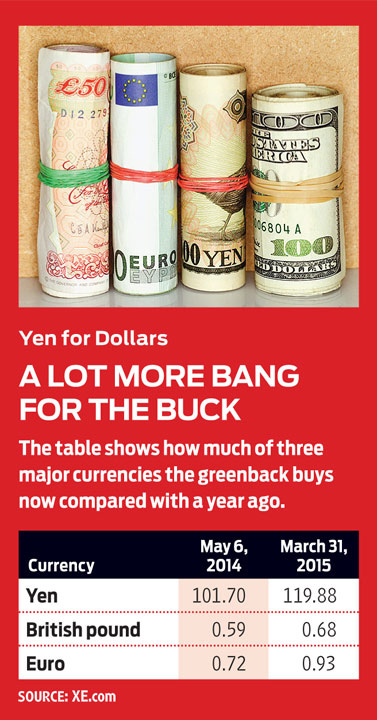

Up 24% against major currencies since May 2014, the greenback is putting pressure on earnings of U.S. exporters and multinationals.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Why has the dollar been so strong? A number of reasons. Our economy has been strengthening, especially relative to the economies of Europe and Japan—and even compared with the economy of China, where the rate of growth outpaces ours but is slowing. Our trade balance has improved, thanks to a boom in energy production, which has drastically cut oil imports. At the same time, the U.S. budget deficit is shrinking. That all helps to attract investment in the U.S. But a huge impetus for the surging dollar is the gap between interest rates here and abroad. The 1.9% yield on the 10-year Treasury bond may seem paltry, but it beats 0.2% on Germany’s 10-year note and 0.4% on Japan’s. That situation is unlikely to change soon. The Federal Reserve is the only major central bank expected to raise rates this year; many others have cut rates or are providing monetary stimulus in other ways.

How does a strong dollar affect the world’s economies? A stronger dollar has been a lifeline for struggling economies in Europe and Japan, boosting exports, relieving deflationary pressures and lifting global growth in general. But a beefier greenback is bad news for financially stressed countries with high debt burdens denominated in dollars. In that camp put South Africa, Turkey and Venezuela. Because oil and other commodities are priced in dollars, the currency’s strength hurts commodity exporters (such as Brazil and Russia) while helping heavy commodity users (China). In the U.S., the economic impact of a stronger dollar will likely be modest; figure that every 20% rise in the dollar might shave a half-point from growth in gross domestic product. The brawny buck detracts from growth because it hurts sales of U.S. exporters, whose products become more expensive overseas. By the same token, imports get cheaper, and that helps boost consumers’ purchasing power—and their spending accounts for 68% of U.S. GDP.

What does the super buck mean for U.S. investors? Over the long haul, not much. The direction of the dollar isn’t a reliable predictor of stock prices in itself. For example, stock prices and the value of the dollar rose simultaneously between 1980 and 1985, but moved in opposite directions from 1985 to 1987. From 1995 to 2001, both were on the upswing, but from 2001 to 2008, the dollar sank and stocks rose. Since 2011, the dollar and stocks have risen in tandem. At the sector level, though, a rising dollar seems to favor stocks of companies that depend on consumer spending on non-necessities (think retailers and restaurants) and financial firms, while energy companies thrive when the currency is weak.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Then why has dollar news been roiling the U.S. stock market? Investors worry about the hit to the earnings of U.S. exporters and multinationals. A strong greenback hurts firms with foreign operations because sales and profits generated abroad translate into fewer dollars. Overall, firms in Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index derive 46% of sales overseas; for energy and materials companies, it’s a bit more than that. Technology firms depend on foreign sales for 56% of revenues. In January, analysts expected that earnings for tech companies would rise more than 10% in 2015; forecasts now call for growth of just 6%. Firms warning that the stronger dollar will hurt 2015 results range from DuPont to PepsiCo.

How much more can the dollar appreciate? Most of the move has been made. In fact, some analysts think the dollar has already peaked. For the dollar and euro to be at parity—that is, one dollar equals one euro—the buck would have to increase 8%. To expect that to happen seems a stretch, at least for now.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Anne Kates Smith brings Wall Street to Main Street, with decades of experience covering investments and personal finance for real people trying to navigate fast-changing markets, preserve financial security or plan for the future. She oversees the magazine's investing coverage, authors Kiplinger’s biannual stock-market outlooks and writes the "Your Mind and Your Money" column, a take on behavioral finance and how investors can get out of their own way. Smith began her journalism career as a writer and columnist for USA Today. Prior to joining Kiplinger, she was a senior editor at U.S. News & World Report and a contributing columnist for TheStreet. Smith is a graduate of St. John's College in Annapolis, Md., the third-oldest college in America.

-

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost You

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost YouTaxable Income When Super Bowl LX hype fades, some fans may be surprised to learn that sports betting tax rules have shifted.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into AMD Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into AMD Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayAdvanced Micro Devices stock is soaring thanks to AI, but as a buy-and-hold bet, it's been a market laggard.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into UPS Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into UPS Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayUnited Parcel Service stock has been a massive long-term laggard.

-

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second Term

How the Stock Market Performed in the First Year of Trump's Second TermSix months after President Donald Trump's inauguration, take a look at how the stock market has performed.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Lowe's Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Lowe's Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayLowe's stock has delivered disappointing returns recently, but it's been a great holding for truly patient investors.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into 3M Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into 3M Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayMMM stock has been a pit of despair for truly long-term shareholders.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Coca-Cola Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Coca-Cola Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayEven with its reliable dividend growth and generous stock buybacks, Coca-Cola has underperformed the broad market in the long term.

-

If You Put $1,000 into Qualcomm Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You Would Have Today

If You Put $1,000 into Qualcomm Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You Would Have TodayQualcomm stock has been a big disappointment for truly long-term investors.

-

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Home Depot Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have Today

If You'd Put $1,000 Into Home Depot Stock 20 Years Ago, Here's What You'd Have TodayHome Depot stock has been a buy-and-hold banger for truly long-term investors.