Target-Date Funds Reset Their Sights

Fund companies are tinkering with these one-stop retirement plans after their bear-market beating.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

From U.S. senators to government regulators to shell-shocked investors, everyone, it seems, is drawing a bead on target-date funds for producing such rotten results during the 2007-09 bear market. These funds were supposed to be simple solutions for retirement saving: You picked a fund with a date close to your anticipated retirement. As the date approached, the fund would adjust the bond portion of its portfolio to become more conservative and protect returns.

But that’s not exactly how it worked. Take 2010 funds, for example, which were designed for investors at or near retirement now. On average, those funds lost 34% of their value during the bear market. That was still better than the 55% drop in Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, but it was a big hit for investors in the critical first years of retirement.

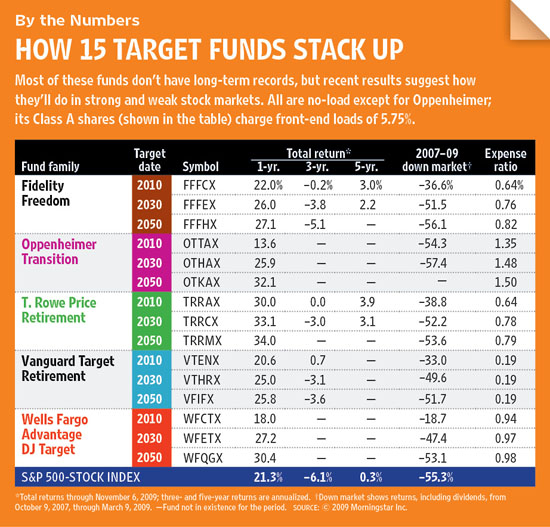

And because each family of target-date funds has its own mix of assets -- and follows its own so-called glide path when shifting to more-conservative investments -- fund performance varied considerably. For instance, the worst-performing 2010 fund, Oppenheimer Transition, had 66% of its portfolio in stocks, plus a big bond holding that tanked. As a result, it posted a decline of 54%. But Wells Fargo Advantage Dow Jones Target 2010 had just 25% of its assets in stocks. It lost only 19% during the same period (see the table below).

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Full disclosure

Those results prompted the U.S. Senate, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Labor to pile on with hearings investigating the use of target-date funds in retirement plans. Let us be upfront about where we stand: We have always liked target-date funds and still do, even when they invest aggressively (within reason) in stocks. Some lawmakers have pushed for regulators to establish asset-allocation guidelines for the funds. We disagree -- that’s a job for fund managers. But investors do need to know what’s in these funds and how best to manage them as part of their overall investments.

That’s especially true because target-date funds are popular default options in retirement plans. If you don’t choose your own investments in a 401(k) plan, for example, your employer may deposit your contributions into a target-date fund. Congress permitted this with the Pension Protection Act of 2006, and since then the number of plans that automatically funnel 401(k) contributions into target-date funds has more than doubled. According to Vanguard, one of the three largest providers of target-date funds as measured by assets, the percentage of plans it manages that use these funds as default options grew from 42% in 2005 to 87% in 2008. Fidelity, another top target-fund sponsor, experienced a similar pattern in the plans it manages.

And target-date funds may blossom into something even bigger because younger workers are more likely to own them. Casey Quirk, a consulting firm, projects that money in target-date funds will grow 11-fold, to $2.6 trillion, by 2018. The firm assumes that target funds will attract 80% of the new money going into retirement plans over the next decade. At the end of 2008, 43% of retirement-plan participants in their twenties owned these funds, up from 29% in 2007, reports TD Ameritrade. That compares with just 22% of savers in their sixties.

But many investors don’t understand how target-date funds work. A recent study by Envestnet Asset Management and Behavioral Research Associates found that only 16% of investors had even heard of target-date funds. Of that group, 62% thought they would be able to retire when the fund reached its target date, and 38% thought their fund had a guarantee.

Target funds were designed to be the only investment you’d need for retirement. But people rarely use them that way. Only 19% of investors put as much as 80% to 100% of their assets in a target-date fund, according to a survey by AllianceBernstein.

And there’s another sticking point: A fund’s glide path doesn’t necessarily stop when you expect it to stop. Instead of ending in, say, 2010 or 2030, all of the major target-date funds continue to increase their bond allocations decades after the target date. “If it’s a 2030 fund, the glide path should end in 2030,” says Michael Case Smith, target-date portfolio manager at investment firm Avatar Associates. Fees also remain a concern. Some sponsors charge a management fee on top of expenses levied by the underlying funds in the target-date portfolios.

The right balance

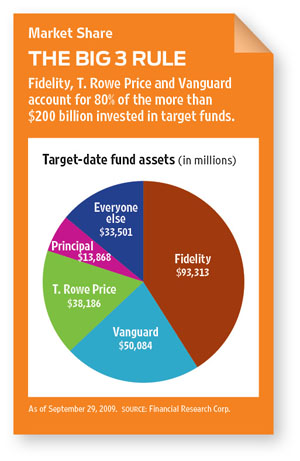

Nearly 50 fund sponsors offer target-date funds, but three dominate the business. Funds from Fidelity, T. Rowe Price and Vanguard account for 80% of the $229 billion invested in target-date funds as of September 2009, according to Financial Research Corp. These three sponsors generally provide diversified portfolios with low fees. But there are significant differences among the trio:

T. Rowe Price: Most aggressive. Managers at T. Rowe Price are unabashed about investing heavily in stocks to guard against the risk that investors will run out of money in retirement. The company’s target-date funds hold as many as 17 other Price funds -- including Kiplinger 25 members T. Rowe Price Mid-Cap Growth and T. Rowe Price Emerging Markets Stock. Funds that are furthest from their targets start out with 90% of their assets in stocks. They continue to hold about 60% in stocks when they hit their mark.

By comparison, Fidelity and Vanguard funds have 50% of their assets in stocks at their target date. Even 30 years after the target date, the Price funds still have a 20% stake in stocks. Meanwhile, Vanguard reduces its stock holdings to 30% after eight years; Fidelity’s timetable is 15 years.

Those numbers actually understate the aggressiveness of some target-date funds. T. Rowe Price’s 2010 fund holds 16% of its assets in high-yield, or junk, bonds, which are similar to stocks in terms of risk (Fidelity’s 2010 fund has a 20% stake in junk).

T. Rowe Price has no plans to change its strategy. Even though its 2010 fund fell 39% in the bear market, the fund had recovered most of that ground as of November 6. “We are staying the course,” says Jerome Clark, manager of T. Rowe Price’s retirement funds. “Having a higher stock allocation, even in retirement, defends against inflation and the risk that you’ll outlive your money.”

Vanguard: Lowest fees. We agree that stocks will perform well over a long period of time, and that’s why T. Rowe Price’s target-date funds are among our favorites. But what if you don’t want more than 70% of your assets in risky investments when you’re ready to retire? In that case, Vanguard funds are a solid choice.

Vanguard Target Retirement funds use a portfolio of five index funds plus actively managed money-market and Treasury inflation-protected securities funds (but no junk bonds). “It was the funds’ broad diversification that enabled them to avoid the worst of the market losses,” says John Ameriks, head of investment counseling and research at Vanguard. The 2010 fund lost 33% in the bear market and returned 0.7% annualized over the past three years through November 6.

And expenses are rock-bottom. The funds charge an annual fee of 0.18% or 0.19%, the lowest in the category.

Fidelity: In the middle. Fidelity’s Freedom funds, which debuted in 1996, are the largest family of target-date funds as measured by assets. They invest in a portfolio of Fidelity funds (but not Kiplinger 25 members Contrafund and Low-Priced Stock). Stacked up against T. Rowe Price and Vanguard, the Freedom funds are in the middle -- not quite as aggressive as T. Rowe Price nor as cheap as Vanguard, but still attractive. The Fidelity 2010 fund lost 37% in the bear market but gained 3% annualized over the past five years through November 6. Fidelity also offers Fidelity Advisor funds sold through advisers, but they’re more expensive than the Freedom funds and their track records aren’t as good.

Some target-fund sponsors are trying completely different strategies. Putnam, for example, uses an “absolute return” approach in its ten Retirement-Ready funds. That means that over three-year periods the funds will try to generate returns that average one, three, five or seven percentage points per year above the inflation rate. But those returns aren’t guaranteed. With annual expenses between 1.25% and 1.34% and short track records, it remains to be seen whether the Putnam funds can deliver.

Schwab, on the other hand, has ramped up the stock portion of its 2040 fund from 79% to 91%, while scaling back stocks in its 2010 fund from 52% to 43%. “We really needed to reduce stock exposure in the years approaching the target date because that’s when our clients are most vulnerable,” says Daniel Kern, portfolio manager of the Schwab Target funds. “They have the most money at risk, limited earning power remaining in their careers and the highest level of anxiety.”

What you can do

When the dust settles, expect to see more disclosure about how funds invest after they hit their target date. Also, more firms will experiment with guarantees. For instance, Prudential offers products that allow retirement-plan participants to invest in target-date funds with guaranteed minimums of lifetime income. Prudential’s guarantee comes with a 1% annual fee in addition to the 0.59% expense ratio the target-date funds charge. Other firms, such as AllianceBernstein, are developing similar products.

But even these aren’t perfect. “With guaranteed options, there are concerns over cost and portability,” says Eric Endress, an analyst with CBIZ Financial Solutions who reviews target-date funds for plan sponsors. Guarantees cost more. Plus, most investors move their assets out of employer plans once they retire, so they end up paying for income guarantees they don’t use. Investors would also lose the guarantee if they rolled their accounts over to another firm.

In the meantime, you can ease your mind about your target-date fund by peeking under the hood. Morningstar now rates 20 families of target-date funds, and its Instant X-Ray tool gives you a clear view of your holdings and how much you have in stocks and bonds. In addition, the major fund sponsors provide details about their glide paths and asset allocations on their Web sites. And at www.djindexes.com, you can compare target funds’ performance against that of the Dow Jones Target Date indexes for free.

It’s also possible to cut the risk of your target-date fund by moving 10% of your retirement contributions into a high-quality bond fund or a stable-value fund, if your company retirement plan offers one (see Stable Funds in Chaotic Times). That’s not a bad move if you are within ten years of retirement and want less volatility. But you have to strike a balance between the risk of losing your principal and the risk of running out of money before your retirement ends.

Bottom line: All the fuss over target-date funds will mean little to most investors. As the markets recover, the debate sounds a lot like Monday-morning quarterbacking. Know what’s in your target fund and view it in the context of your overall assets. If you want to make drastic alterations to your fund, best to find another target fund that suits you. Or roll up your sleeves and build a portfolio of no-load funds from scratch.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Clients

Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Clientswealth management These banks welcome customers who keep high balances in deposit and investment accounts, showering them with fee breaks and access to financial-planning services.

-

Stock Market Holidays in 2026: NYSE, NASDAQ and Wall Street Holidays

Stock Market Holidays in 2026: NYSE, NASDAQ and Wall Street HolidaysMarkets When are the stock market holidays? Here, we look at which days the NYSE, Nasdaq and bond markets are off in 2026.

-

Stock Market Trading Hours: What Time Is the Stock Market Open Today?

Stock Market Trading Hours: What Time Is the Stock Market Open Today?Markets When does the market open? While the stock market has regular hours, trading doesn't necessarily stop when the major exchanges close.

-

Bogleheads Stay the Course

Bogleheads Stay the CourseBears and market volatility don’t scare these die-hard Vanguard investors.

-

The Current I-Bond Rate Is Mildly Attractive. Here's Why.

The Current I-Bond Rate Is Mildly Attractive. Here's Why.Investing for Income The current I-bond rate is active until April 2026 and presents an attractive value, if not as attractive as in the recent past.

-

What Are I-Bonds? Inflation Made Them Popular. What Now?

What Are I-Bonds? Inflation Made Them Popular. What Now?savings bonds Inflation has made Series I savings bonds, known as I-bonds, enormously popular with risk-averse investors. How do they work?

-

This New Sustainable ETF’s Pitch? Give Back Profits.

This New Sustainable ETF’s Pitch? Give Back Profits.investing Newday’s ETF partners with UNICEF and other groups.

-

As the Market Falls, New Retirees Need a Plan

As the Market Falls, New Retirees Need a Planretirement If you’re in the early stages of your retirement, you’re likely in a rough spot watching your portfolio shrink. We have some strategies to make the best of things.