Where to Invest in 2010

The long-term economic outlook remains gloomy, but stocks should still advance in the coming year.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

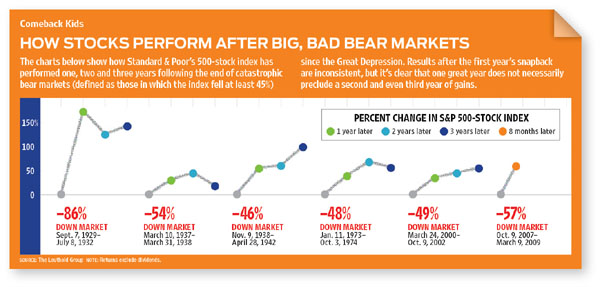

If you relish drama, 2009 had it all. In a cliffhanger, the very visible hand of government helped wrest the U.S. economy from the abyss. Following the longest and steepest recession since World War II, initial reports indicated gross domestic product grew 3.5% in the third quarter. Anticipating the end of the downturn, a nearly comatose stock market bottomed on March 9, then soared 60% in just seven months.

What’s in store for 2010? Recessions stemming from financial crises tend to be severe and are usually followed by relatively anemic economic recoveries. This time will be no exception, with one of the feeblest recoveries -- maybe 2% to 3% growth in GDP in 2010 -- to follow such a steep decline.

Moreover, Uncle Sam has extended enormous fiscal and monetary stimuli in order to stem the downward spiral. Low interest rates may benefit debtors, but they punish savers. Massive amounts of private-sector indebtedness have been shifted onto the shoulders of government -- and taxpayers. Eventually, the bill will come due.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The stock-market rally of 2009 had an artificial feel. It owed more to a sea of liquidity than to an improvement in the nation’s basic economic condition. When the Federal Reserve Board loosens monetary policy and short-term interest rates fall to zero, capital flows more quickly to risky assets, such as stocks and junk bonds, than it does to the real economy.

There may well be a day of reckoning for all the lingering structural imbalances, but we’re betting that it won’t come in 2010, a midterm election year. Somewhat surprisingly, then, this year may turn out to be a good one for the stock market.

With Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index selling in early November at about 15 times estimated 2010 earnings, the market’s price-earnings ratio is in line with the historical average. Driven by improving earnings in the new year and the prospect of more of the same in 2011, a broad index such as the S&P 500 could return about 10% over the next 12 months. In terms of the market’s best-known barometer, the Dow Jones industrial average could approach 11,000.

David Bianco, chief market strategist for Merrill Lynch, thinks earnings will be surprisingly strong given expectations of modest GDP growth. A weak dollar benefits many businesses, including resource producers. Industries such as technology, energy and materials now book more than half of their revenues overseas, where economic growth is stronger than at home. “The S&P 500 is beginning to outgrow the U.S.,” Bianco says.

Those scary deficits

But investors need to be aware of the many lurking risks. Let’s start with the federal budget deficit, which also intersects with currency, interest-rate and inflation risks. Goldman Sachs projects that outlays will exceed income by $1.6 trillion in the fiscal year that ends next September and by another $1.4 trillion the following year. Tax revenues at the federal level are running at only 60% of spending levels, and let’s not forget that nearly every state is running a deficit, too.

Those are frightening numbers, but just as scary is the domestic savings shortfall, which means that we must depend on the kindness of foreign strangers, such as the Chinese, Japanese and Russians, to purchase half of the Treasury bonds we sell at auction. Will they?

Maybe they will, but probably at the price of higher interest rates and a cheaper dollar. This is a high-stakes confidence game. Turner Investment’s David Kovacs says two nightmare scenarios for 2010 would be a foreign selloff of bonds and a Treasury-bond auction for which, figuratively speaking, no one showed up. Either would force the Fed to raise interest rates much sooner than it intended.

The fundamental problem is that we have massive budget deficits but artificially low interest rates. The Fed is keeping rates low to ease the strains of high unemployment, excessive consumer debt and a moribund residential real estate market, and to help ailing banks earn easy profits from the wide spreads between their cost of money and the interest rates they charge.

Economists at Goldman Sachs think that deflationary pressures in the economy are so potent that the Fed -- if left to its own devices -- will not start raising interest rates until 2011. Indeed, slashing debt is deflationary, and there are high levels of slack capacity in labor, real estate and industrial markets. For instance, rents -- which account for almost 40% of inflation calculations -- are declining.

Yet investors such as Rob Arnott, of Research Affiliates, are already fretting about looming risks of inflation and increased currency weakness as the government strains to reignite the economy. “It’s hard to imagine setting trillion-dollar bonfires in fiscal and monetary stimulus without triggering a pretty severe risk of inflation down the road,” says Arnott. He believes the Fed and the Treasury Department will encourage some inflation to ease the nation’s debt burden, while at the same time denying that they are doing so. He expects inflation, recently running at an annual rate of Ð1.3%, to top 3% by 2011.

Today, many of the vestiges of our epic credit and housing bubbles remain. The banking system, the lifeblood of our economy, is still convalescing. U.S. banks will have written down more than $1 trillion of bad loans by the end of 2010, projects the International Monetary Fund. Losses on commercial real estate loans are mounting. That will endanger numerous community and regional banks. Meanwhile, net lending by banks has declined sharply in recent months, and small enterprises, which depend heavily on bank credit, are having trouble securing loans. Banks seem more interested in rebuilding their balance sheets by borrowing cheap money and investing in Treasuries than in lending to small businesses.

Let’s not forget residential housing, the proximate trigger of the financial collapse. In recent months, housing prices have stabilized after a three-year downward spiral. But home prices may start declining again in 2010 if the government begins to ease some of the programs designed to prop up housing prices (see Glimmers of Light on Home Prices).

Amherst Securities calculates that seven million loans -- a truly staggering number -- are delinquent or in foreclosure, which creates a large overhang weighing on the market. And the meaning of delinquency has changed over the past decade. Amherst says that in 2005, before negative home equity entered our lexicon, two-thirds of delinquent loans were cured without resorting to foreclosure. Today, a loan delinquent for 60 days or more has a 95% chance of ending in foreclosure.

There is a silver lining for banks, however, in the process of clearing foreclosures, says Dave Ellison, manager of FBR Large Cap Financial fund. From the moment the homeowner stops paying his mortgage until foreclosure -- typically a span of more than a year -- banks receive no income from the property. But once a bank takes possession of a property, it regains value because the bank can sell the home to the highest bidder.

Falling housing values are at least partly to blame for the shift to thrift among U.S. consumers. Households are laboring to reduce heavy debts in a difficult environment of stagnant incomes, a poor job market and deflated net worth. “We think it will take three to five years for the consumer to fix his balance sheet,” says Charles de Vaulx, co-manager of IVA Worldwide Fund.

The jobs figures are awful -- a 10.2% unemployment rate at last report and more than seven million jobs lost during the recession. Economists at ING project that a return to full employment over the next five years would require 15 million new jobs, or 250,000 per month (from 1999 through 2008, the economy generated 50,000 new jobs monthly). That’s just not going to happen. Many of the jobs in bloated sectors, such as real estate, construction, finance and retail, are not returning anytime soon.

A focus on earnings

Clearly, the U.S. faces many long-term structural problems. But the stock market, which began its remarkable leap after investors concluded that economic Armageddon was no longer at hand, will advance as it responds to an improving earnings picture. And treading carefully amid the wreckage in the economy, investors can still find some alluring themes.

One idea is to invest in blue-chip companies with strong foreign sales. Mike Avery, co-manager of Ivy Asset Strategy, a global fund, hunts for “best in class” U.S. companies with strong overseas footprints. His U.S. multi-national holdings include Monsanto (symbol MON), Apple (AAPL) and Nike (NKE).

Channing Smith, co-manager of Capital Advisors, says he holds YUM Brands (YUM), which operates KFC and Pizza Hut restaurants, for its large and fast-growing China business. He gravitated toward Procter & Gamble (PG), which sells affordable necessities, such as diapers and razor blades, for similar reasons.

Information technology, an area in which the U.S. leads, also benefits from global economic recovery. Alan Gayle, senior investment strategist of SunTrust’s RidgeWorth Investments, says many tech giants have strong balance sheets with little debt and sport impressive profit margins. Stocks he likes include Adobe Systems (ADBE), Hewlett-Packard (HPQ) and Microsoft (MSFT).

Like the technology sector, the energy and materials industries generate the bulk of their sales abroad. But exports and overseas sales are only part of the story for these businesses. Commodities, such as oil and iron, are traded globally and priced in dollars, so if demand from emerging markets and a weak buck drive up prices, the natural-resources producers benefit.

Jerry Jordan, manager of Jordan Opportunity Fund, expects another onslaught of commodity-price inflation over the next couple of years -- particularly in areas that have little new capacity coming on-stream, such as oil and copper. He likes oil-equipment and energy-services companies, including National Oilwell Varco (NOV) and Halliburton (HAL).

Jordan is also a bull on agriculture, reasoning that the rapidly rising consumption of animal protein in emerging markets will boost demand for grain used to feed livestock. His main plays on food are through a pork producer in China and through PowerShares DB Agriculture (DBA), an exchange-traded fund that holds futures contracts on grains and sugar. Rich Howard, co-manager of Prospector Opportunity, favors DuPont (DD). The chemical giant has a large and growing seed-technology business that competes with Monsanto’s.

Like many others worried about the health of the U.S. dollar and other major currencies, Howard has become a gold bug. He’s allocated 10% of his portfolio to mining stocks, including Barrick Gold (ABX) and Newmont Mining (NEM).

You can also profit from more domestically oriented stocks. Smith believes that companies such as Wal-Mart Stores (WMT) and PetSmart (PETM) will benefit from the new frugality of U.S. consumers (see What’s in Store for the Next Decade). He recently purchased shares of CarMax (KMX), the largest used-car retailer in the U.S. With just 2% of the national market, the company has plenty of room to expand.

Health care is a huge and growing domestic industry that’s difficult to ignore. But uncertainty about the direction of health-care reform makes investing tricky. Smith favors companies that will benefit from cost reduction and expanded insurance coverage, such as Quest Diagnostics (DGX), which provides testing services, and McKesson (MCK), a leading drug distributor. He’s also bullish on Abbott Laboratories (ABT), a diversified, steady grower that he considers undervalued.

You can, of course, invest in themes such as these through diversified funds. For instance, Fidelity Contrafund (FCNTX) and Selected American Shares (SLASX) are both stuffed with large, blue-chip U.S. companies with sturdy foreign franchises. For a fund tilted more toward tech and health stocks, consider Primecap Odyssey Growth (POGRX).

If you expect prices of oil, gold, grains and other stuff to continue to rise, you can invest through a fund such as Pimco CommodityRealReturn Strategy (PCRDX), which seeks to track commodity futures prices. Or you can buy into a fund such as T. Rowe Price New Era (PRNEX), which invests in stocks of natural-resources companies.

If all of the many risks out there scare you, then take a look at FPA Crescent (FPACX), which has the ability to sell stocks short (that is, bet on their share prices to fall) and to invest in bonds and bank loans. Crescent has a long history of enjoying most of the gains of bull markets and protecting capital during tough times.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Andrew Tanzer is an editorial consultant and investment writer. After working as a journalist for 25 years at magazines that included Forbes and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance, he served as a senior research analyst and investment writer at a leading New York-based financial advisor. Andrew currently writes for several large hedge and mutual funds, private wealth advisors, and a major bank. He earned a BA in East Asian Studies from Wesleyan University, an MS in Journalism from the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, and holds both CFA and CFP® designations.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

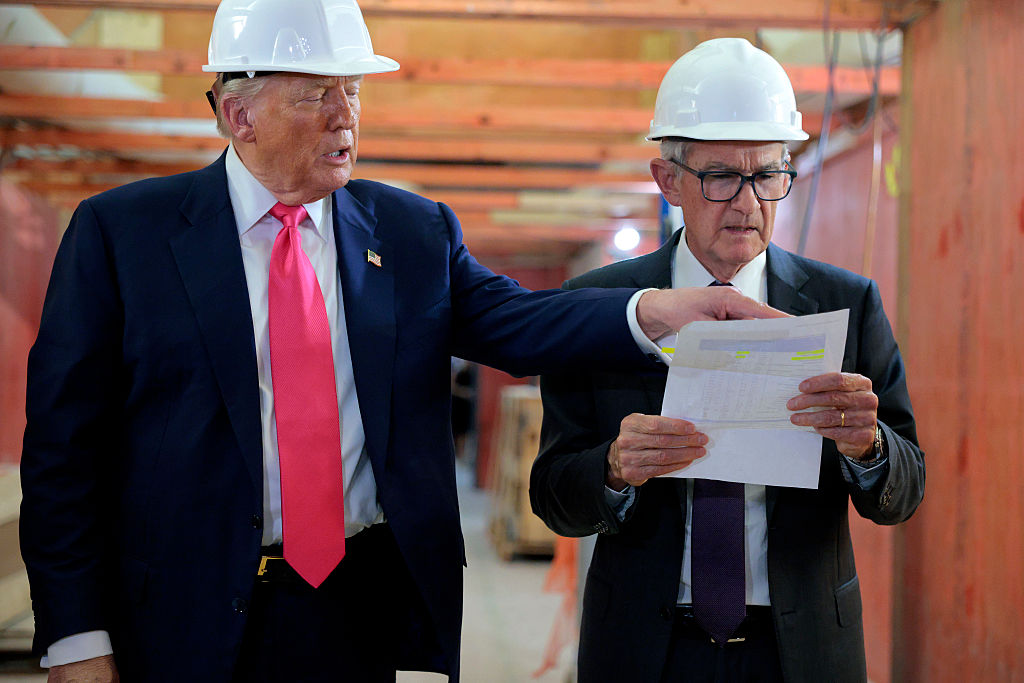

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.

-

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising Prices

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising PricesThe November CPI report came in lighter than expected, but the delayed data give an incomplete picture of inflation, say economists.

-

The Delayed November Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed and Rate Cuts

The Delayed November Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed and Rate CutsThe November jobs report came in higher than expected, although it still shows plenty of signs of weakness in the labor market.

-

December Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

December Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe December Fed meeting is one of the last key economic events of 2025, with Wall Street closely watching what Chair Powell & Co. will do about interest rates.