Income Investors, Don't Fret About Higher Interest Rates

Much of your portfolio's performance will depend on the kinds of bonds you own and their maturities, which should be a lot less than 10 years.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

The vast majority of investing seers were betting their right arms one year ago that interest rates would rise enough in 2014 to inflict severe pain on holders of bonds and other income-oriented investments. That was an epic misjudgment, and we’re glad to say that you read no such dire warning here.

SEE ALSO:

Hedge Against Higher Rates with Bank Stocks

p>

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

As it turned out, 2014 was wonderful for holders of bonds and other income investments. Over the past year, the yield of the benchmark 10-year Treasury bond dropped from 2.6% to 2.3%. Because bond prices move opposite to interest rates, long-term government debt returned 13.1% over the past year (returns and yields are through October 31). Municipals went wild, propelled by improved credit quality and tight supply; they returned 12.6%. Real estate investment trusts and utilities also performed spectacularly. Energy income securities prospered until oil prices slumped. Junk bonds essentially earned their coupons, returning 5.9%.

For the coming year, expect interest rates to rise slightly and returns to moderate. But there’s no need to panic. The near-absence of inflation, the powerful dollar and fair U.S. growth juxtaposed against economic weakness and disorder almost everywhere else keeps U.S. income investors in a sweet spot. “The basic story is that the U.S. economy is better than any in the world, so U.S. financial assets should do better than any others,” says Krishna Memani, chief of fixed income for Oppenheimer Funds and one of the few pros who got 2014 right.

You might think that a revived U.S. economy would send rates here soaring. But instead of jacking up borrowing costs, a healthy U.S. attracts cash from all over the world, helping to restrain rates. Foreigners are gorging on Treasury debt with little regard to yield, figuring that getting paid in a robust currency from a stable country is a safer and potentially more rewarding bet than investing at home.

At the same time, other anti-bond arguments keep falling apart. Investors seem unconcerned that the Federal Reserve has voted to end its massive bond-buying program. As for lifting short-term rates, the next step in returning to a more normal monetary policy, it’s unlikely that the Fed will do anything until summer at the earliest.

Rate outlook. I grant that as yields have come down, the risk of owning bonds has gone up. For a look at what you might lose if rates reversed course, I commend to you What Will Higher Rates Do to the Kip 25 Bond Funds?. Figure on 10-year Treasuries yielding between 2.25% and 3.25% over the coming year. Given that rates are near the bottom of that range, you would probably lose money if you bought a long-term bond today and sold it in 2015. But much of your portfolio’s performance will depend on the kinds of bonds you own and their maturities, which should be a lot less than 10 years. I favor middle-of-the-road bond funds—such as Fidelity Total Bond (FTBFX), a member of the Kip 25—and medium-maturity municipal bonds, as well as REITs for more aggressive investors.

I close with another dose of reassurance: If the Fed were to embark on a vigorous rate-hiking campaign, such a move would surely crush any inflation anxiety. That, in turn, would lessen the likelihood of long-term rates rising significantly. This is the pattern Memani expects. So does the team at Metropolitan West funds, where the talk is of a “flatter yield curve over time.” In plain English, that means you would finally earn more on CDs, money market funds and short-term debt. But you wouldn’t lose all that much on long-term government and corporate bonds.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Kosnett is the editor of Kiplinger Investing for Income and writes the "Cash in Hand" column for Kiplinger Personal Finance. He is an income-investing expert who covers bonds, real estate investment trusts, oil and gas income deals, dividend stocks and anything else that pays interest and dividends. He joined Kiplinger in 1981 after six years in newspapers, including the Baltimore Sun. He is a 1976 journalism graduate from the Medill School at Northwestern University and completed an executive program at the Carnegie-Mellon University business school in 1978.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

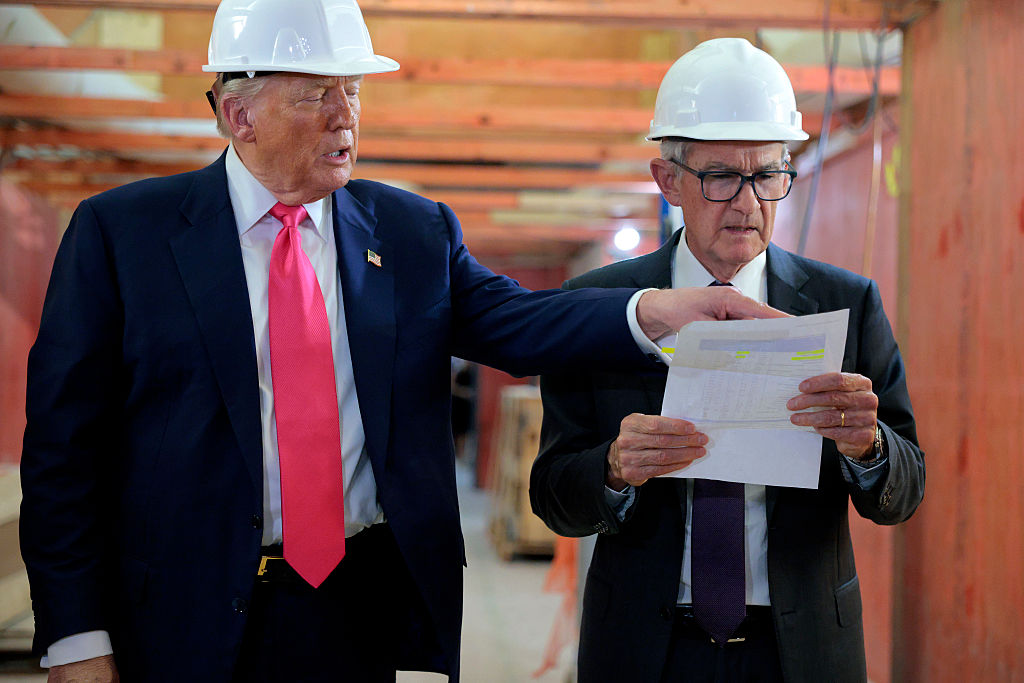

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.

-

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising Prices

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising PricesThe November CPI report came in lighter than expected, but the delayed data give an incomplete picture of inflation, say economists.

-

The Delayed November Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed and Rate Cuts

The Delayed November Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed and Rate CutsThe November jobs report came in higher than expected, although it still shows plenty of signs of weakness in the labor market.

-

December Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

December Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe December Fed meeting is one of the last key economic events of 2025, with Wall Street closely watching what Chair Powell & Co. will do about interest rates.