Buy Retail Stocks at Wholesale Prices

Department-store stocks have lost one-fifth of their value in the past five years, while the overall stock market has nearly doubled.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

I’m constantly looking for unloved sectors, but in a bull market that just celebrated its eighth birthday, despised industries aren’t easy to find. Over the past five years, energy was down a bit and real estate was flat, but both have bounced back lately. In the past 12 months, the overwhelming majority of sectors tracked by Standard & Poor’s registered gains. One notable exception: department-store stocks.

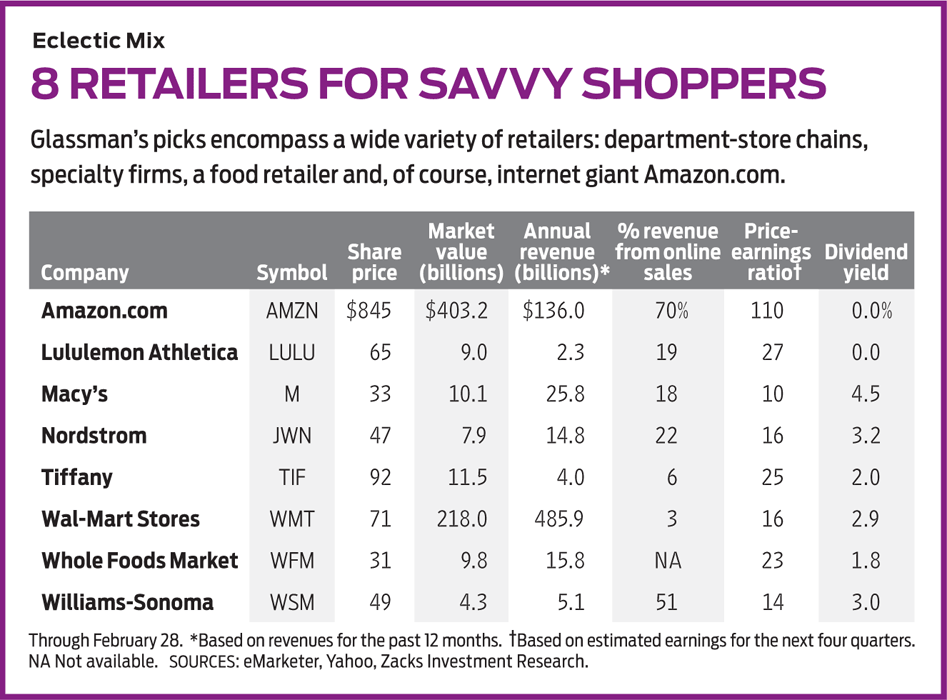

Shares of so-called multi-line retailers have lost one-fifth of their value in the past five years, according to research firm Morningstar, while Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, the large-company benchmark, has nearly doubled. Sears Holdings (symbol SHLD), once the proudest name in retailing, has fallen by more than half in the past 12 months. Specialty retailers have suffered, too. Sports Authority, Limited Stores and Wet Seal have all filed for bankruptcy protection. Other retailers, such as Barnes & Noble (BKS), with a market value of $713 million, are shadows of their former selves. Still others, including Bon-Ton Stores (BONT), down more than 90% since 2013, are on the brink of collapse. (All share prices and returns are as of February 28.)

Bargain hunter’s dream. This devastation is delightful for contrarian investors. The misery of retailers has given the sector such a bad name that perfectly decent companies are now on sale. A curious fact about human nature is that, as consumers, people will rush to buy items marked down 40% by a clothing shop or an airline, but, as investors, they will shun stocks that have fallen in price.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Retailers were hurt by the recession of 2007–09 and the sluggish economic growth that followed, with consumers paying off debt and unwilling, or unable, to borrow against the value of their homes. But the internet is the main reason many retailers have run aground.Consumers are moving from brick-and-mortar shops to cyberspace, and traditional stores are floundering. Nearly all are vulnerable, even sellers of clothing. “Department stores,” says a recent Value Line report, “banked on the fact that apparel needed to be tried on, a belief that’s now fading.” Millennials, especially, just don’t like shopping at the mall, so internet-based companies such as Bonobos (which is not publicly traded) let consumers try on clothes in a showroom, establish their sizes and then order only online. Other online retailers offer virtual dressing rooms, taking measurements by webcam. Returns are easy if the clothes don’t fit.

Few retailers have effectively adapted to this new world. Wal-Mart Stores (WMT, $71), the world’s largest retailer, sells only 3% of its goods online; Home Depot (HD) sells 6%; Best Buy (BBY), 12%; and Target (TGT), 4%. The Census Bureau reports that last year, e-commerce sales amounted to $395 billion, and just one company, Amazon.com (AMZN, $845)—a longtime recommendation of mine—accounted for $95 billion of the total, or nearly one-fourth. Amazon sells more online than the next 20 largest internet purveyors combined. It also has a rapidly growing cloud-computing business.

Gadgets and e-commerce. Although internet sales are growing swiftly, we are still in the early days. E-commerce accounts for only 8.1% of total retail sales, a figure that could easily hit 20% in the next 10 years. Which retailers are doing well on the internet besides Amazon? Williams-Sonoma (WSM, $49), for one. The company owns 241 stores that sell high-end kitchen products, plus another 202 Pottery Barn shops and about 200 outlets under other names. Still, Williams-Sonoma gleans half of its $5 billion in sales online—a big reason that annual revenues rose in each of the fiscal years from 2009 through 2015, with more growth expected when the final results are in for the fiscal year that ended in January 2017. The stock trades at a moderate price-earnings ratio of 14, based on analysts’ estimated earnings for the fiscal year that ends January 2018, and yields 3.0%.

Also strong in online sales is Nordstrom (JWN, $47), which collects about one-fifth of its revenues from its excellent internet site. The owner of 118 upscale department stores generated $14.8 billion in revenue in the fiscal year that ended in January 2017, marking the seventh straight year of sales gains. Nordstrom shares, which have dropped 41% since June 2015, are attractively priced and yield an above-average 3.2%.But the classic contrarian retailer is Macy’s (M, $33). There’s no doubt that the department-store chain, which also owns Bloomingdale’s, has been having problems, suffering eight straight quarters of sales declines at stores open for at least a year. (So-called same-store sales are an important barometer for retailers.) Earnings per share dropped 38% from the fiscal year ending in January 2016 to the year ending in January 2017, and 66 stores closed, with more shutting this year.

Nevertheless, Macy’s has a lot going for it, including strong online sales, which represent 18% of total revenues. With about 900 stores, Macy’s has the most powerful brand in retailing today, valuable real estate and a tantalizing dividend yield. The stock has fallen by more than half in eight months, so the dividend yield has jumped to 4.5%. Recent cost-cutting should pay off, and the stock’s P/E, based on expected earnings for the year ahead, is about 10. Macy’s is indeed risky, but it also provides a rare bull-market bargain.

If you invest in Macy’s, you are betting on profits increasing from cost-cutting and smart merchandising. But you can invest in stronger retailers, whose profits have been nearly flat but reliable. The best example is Wal-Mart, which has more than 10,000 stores around the world and more brick-and-mortar revenues than all U.S. e-commerce sales combined. Wal-Mart’s sales crept up 3% in the fiscal year that ended in January 2017—not bad for such a behemoth. But the big reason to buy the stock is its dividend, which has risen 44 years in a row and, at the current share price, produces a yield of 2.9%. Think of Wal-Mart, which has a gorgeous balance sheet, as an increasing annuity. In 2006, it was paying a dividend of 30 cents a year; today, it’s $2.04. One warning, though: Wal-Mart and other large retailers would suffer from tariffs or a border tax on imported goods from countries such as China and Mexico. That would boost prices for customers, and Wal-Mart might lose sales.

Grocers are retailers, too, and a contrarian choice that merits attention is Whole Foods Market (WFM, $31). The largest natural-foods grocer in the country has suffered, with five straight quarters of same-store sales declines, as traditional chains have increased their offerings of organics. The shares are down by half since October 2013, but the company has a strong balance sheet, and it continues to add stores. This is one of those “faith-based” investments that I like. No one can know when Whole Foods will turn around, but it has a powerful name and loyal customers, and I have faith that it will make a comeback. Meanwhile, you can own it for the price you would have paid in 2005.

And two more: Lululemon Athletica (LULU, $65), designer and retailer of yoga-style casual clothing, is more expensive than the others here, trading at 27 times estimated year-ahead earnings. But it’s still a bargain when you consider that Lululemon’s sales and earnings are projected to rise at an annual average of 16% for the next three years, according to Zacks Investment Research. And Tiffany (TIF, $92), whose jewelry sales have suffered from a weak global economy, represents a great wager on a revival.

All of the companies I have recommended should be able to navigate the tricky currents of e-commerce. A smart strategy is to invest in two or three of these stocks.

James K. Glassman, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, is the author, most recently, of Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. Of the stocks mentioned, he owns Amazon.com.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Look Out for These Gold Bar Scams as Prices Surge

Look Out for These Gold Bar Scams as Prices SurgeFraudsters impersonating government agents are convincing victims to convert savings into gold — and handing it over in courier scams costing Americans millions.

-

How to Turn Your 401(k) Into A Real Estate Empire

How to Turn Your 401(k) Into A Real Estate EmpireTapping your 401(k) to purchase investment properties is risky, but it could deliver valuable rental income in your golden years.

-

My First $1 Million: Retired Nuclear Plant Supervisor, 68

My First $1 Million: Retired Nuclear Plant Supervisor, 68Ever wonder how someone who's made a million dollars or more did it? Kiplinger's My First $1 Million series uncovers the answers.

-

Cooler Inflation Supports a Relief Rally: Stock Market Today

Cooler Inflation Supports a Relief Rally: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators welcome much-better-than-hoped-for core CPI data on top of optimism-renewing AI earnings.

-

Stocks Slip as Job Growth Stalls: Stock Market Today

Stocks Slip as Job Growth Stalls: Stock Market TodayThe August jobs report came in much weaker than expected, while the unemployment rate ticked higher.

-

Stock Market Today: Dow Sinks 715 Points as Inflation Unrest Grows

Stock Market Today: Dow Sinks 715 Points as Inflation Unrest GrowsInflation worries are showing up in both hard and soft data.

-

Stock Market Today: Markets Celebrate Trump's Tariff Détente

Stock Market Today: Markets Celebrate Trump's Tariff DétenteConsumer discretionary stocks led 10 of the 11 S&P 500 sector groups well into the green.

-

Stock Market Today: Nasdaq Nabs New High After Jobs Data

Stock Market Today: Nasdaq Nabs New High After Jobs DataThe S&P 500 also closed at its highest level ever, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average was pressured by another down day for UnitedHealth stock.

-

Lululemon Jumps to the Top of the S&P 500 After Earnings. Here's Why

Lululemon Jumps to the Top of the S&P 500 After Earnings. Here's WhyLululemon stock is soaring Friday after the athletic apparel retailer's beat-and-raise quarter.

-

Lululemon Stock's Price Troubles Continue After Earnings

Lululemon Stock's Price Troubles Continue After EarningsLululemon stock is lower Friday after the company's second-quarter revenue came up short and it cut its full-year outlook.

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Struggle After May Jobs Report

Stock Market Today: Stocks Struggle After May Jobs ReportWhile the main indexes made modest moves after this morning's hotter-than-expected payrolls data, GameStop took a notable dive.