Don’t Give Up on Energy Stocks

Remember the “peak oil” fears? Looks like we’ll be pulling oil and gas from the ground for decades to come.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Value hunters, who buy what other investors shun, are facing a tough decision these days. Although the rest of the market has been surging, energy stocks have collapsed. Is oil over? Or is this an incredible buying opportunity, like technology shares in 2002 or practically anything in 2009?

I’m an opportunist. But the extent of the carnage in the energy sector is important to understand. Most energy stocks are tied to the price of petroleum. In June 2014, West Texas Intermediate, the North American crude oil benchmark, was $107 a barrel. At the end of 2019, it was just $51 and change. Natural gas dropped over the same period, from $4.79 per thousand cubic feet to $1.84.

That is the main reason McDermott International, the venerable provider of oil and gas construction services (founded in 1923), filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in January of this year. The stock, which traded as high as $26 at the start of 2018, closed at 70 cents on January 21, when trading on the New York Stock Exchange was suspended.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Shares of offshore driller Noble have dropped 90% in less than two years. Range Resources, bleeding red ink, has suspended its dividend. Chevron recently took a $10 billion hit by writing down the value of its U.S. shale properties, which had once seemed so promising.

In 2008, energy accounted for 13% of the total market capitalization of Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, rivaling health care and technology; today, energy represents less than 4%. Energy Select Sector SPDR (symbol XLE), a popular exchange-traded fund that tracks the energy stocks in the S&P, has dropped an annual average of 3.2% over the past five years, compared with an annual gain of 12.4% for the index as a whole. (Prices and other data are as of January 31.)

This dismal performance is all the more remarkable because the ETF is dominated by giant integrated energy companies. The giants make money from operations both upstream (finding petroleum and getting it out of the ground or the ocean) and downstream (refining and selling it to consumers or turning it into chemicals). When oil prices fall, hurting the upstream business, so do prices for the raw material used in the downstream business.

Awash in oil and gas. Like the prices of other commodities, petroleum prices respond to supply and demand. Thanks to new technology, exploration and production companies can, at relatively low cost, extract oil and gas from pockets previously too hard or too expensive to reach. As a result, supply, especially in the United States, has risen sharply. Domestic oil production more than doubled from 2011 to 2019, and natural gas production has increased by more than one-third, according to Energy Information Administration data.

OPEC, the once-powerful oil cartel, has lost much of its punch to market forces as new sources outside the Middle East have been playing bigger roles. Four of the top five oil producers aren’t even members. (The biggest producers, in order, are the U.S., OPEC heavyweight Saudi Arabia, Russia, Canada and China.)

The notion of “peak oil,” which became fashionable 15 years ago, is now considered humorous. The key variable in supply is extraction. When oil prices rise, companies drill for more. As production increases, prices fall—which spurs drillers to shut down rigs, which causes prices to rise again, and so on.

This cycle is reflected in the rig count. The count was about 2,000 when oil prices were riding high in 2014. Then prices dropped, and rigs fell to about 400 in mid 2016, leading to another bump in prices. A recent Bloomberg headline said the “price collapse” has drillers “hitting the brakes.” Baker Hughes, the oil field services giant, reported at the end of January that 790 rigs were operating in the U.S.; a year earlier, the figure was 1,045.

Meanwhile, demand has been tempered by a sluggish global economy. The U.S. has been puttering along at about 2% growth for a decade now, and China’s growth rate has been slowing lately, hurt by trade friction and, most recently, the coronavirus outbreak.

In addition, concerns about climate change have led to a slow shift from petroleum to renewable energy, such as wind and solar, and an overall flat-lining of energy consumption due to conservation. Last year, Americans used less energy (in terms of BTUs, or British Thermal Units, a common measure) than a quarter-century ago. Our use of renewables has roughly doubled since 2002 (see Invest in the Planet).

Still, at this point, renewables are not a major threat to the incumbents. In 2018, fossil fuels (including coal) accounted for 80% of U.S. energy consumption; renewables, 11%; nuclear power, the rest. Electric cars are catching on, but natural gas and coal generate 62% of the electricity that makes them run; wind and solar, 8%; nuclear and hydro, nearly all the rest.

And demand will continue to grow. In its outlook for 2020, the EIA predicted that energy use will keep rising for the next 30 years, though more slowly than GDP. Renewables will cut into the market share of nuclear and coal in generating electricity, but natural gas will hold its share steady at about three-eighths of the total.

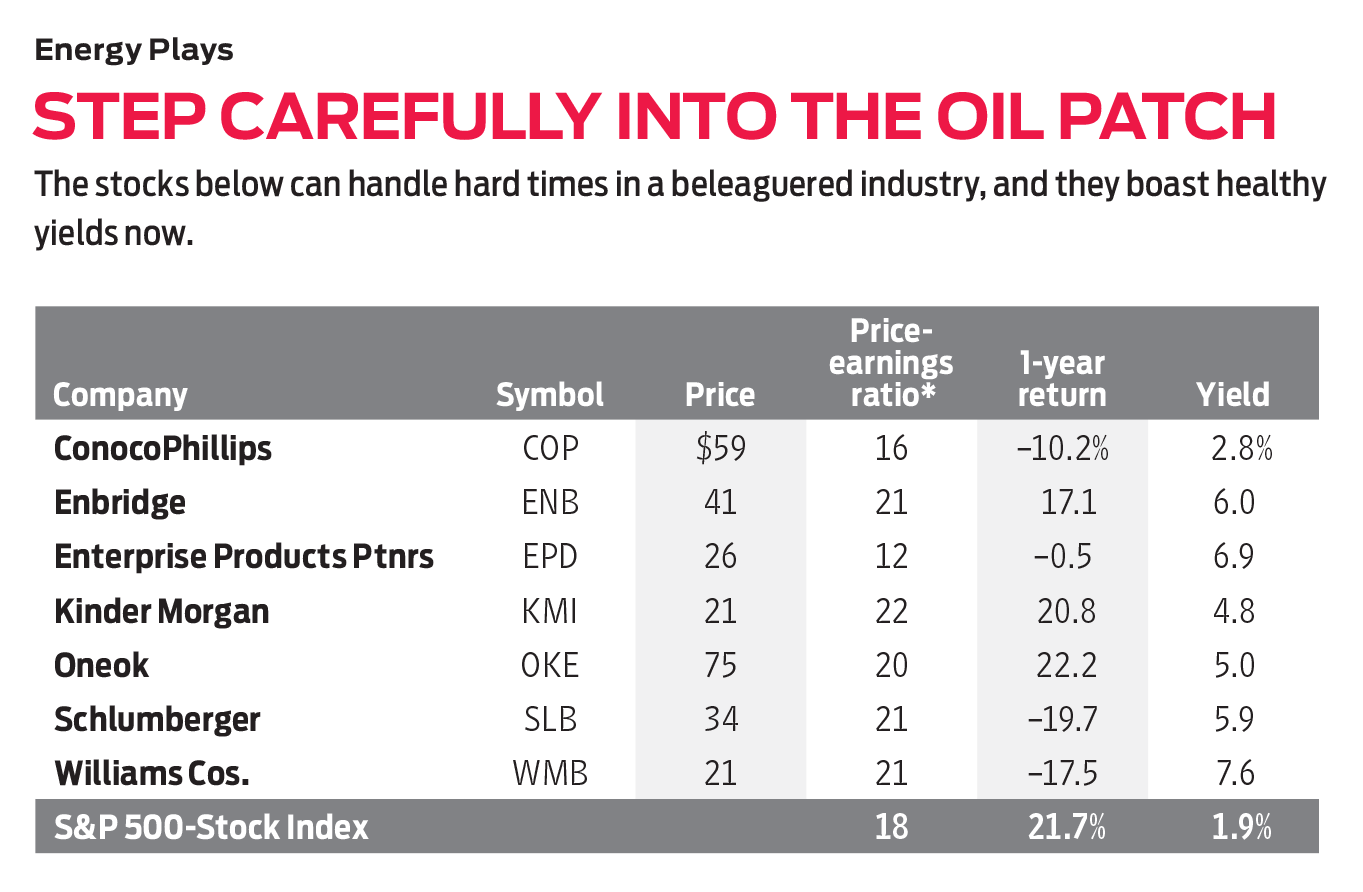

Take the plunge. Guessing the bottom of any cycle is dangerous, but I see significant opportunity in the oil patch. Bad times can be good for the most solid companies as weaker competitors cut back or fail. Schlumberger (SLB, $34), the best of the global oil service firms, trading above $100 a share in 2014, now yields 5.9%. If you believe, as I do, that oil isn’t over, then Schlumberger is an excellent bet. The same applies to ConocoPhillips (COP, $59), an E&P firm with extensive holdings and real staying power, yielding 2.8%.

To make less risky long-term investments, my strong advice is to focus on “midstream” companies, whose main business is gathering, storing and moving petroleum products around. These businesses can be hurt when oil prices fall and their customers suffer, but not nearly as much as E&P and service companies.

You have excellent choices, all of them substantial large caps. My favorite is Kinder Morgan (KMI, $21), which transports oil and gas through 83,000 miles of pipelines and 146 terminals. The stock lost half its value when crude prices crashed in 2015, and it still hasn’t recovered the loss; it yields a lovely 4.8%, nearly three times the rate of a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond.

Another good choice is The Williams Cos. (WMB, $21), which both operates pipelines and processes natural gas. The stock is down by one-third over the past two years, but analysts see revenues and profits rising briskly this year. Williams slashed its dividend in 2016 but has slowly been building it back, and the shares now yield a remarkable 7.6%. I also recommend Oneok (OKE, $75), which, like Williams, is based in Oklahoma and was founded more than a century ago. Shares returned nearly 50% in 2019, but analysts still expect earnings to increase more than 20% in 2020. The stock yields 5%.

Also recommended: Calgary-based Enbridge (ENB, $41), with a market cap of $86 billion and a yield of 6%, and Enterprise Products Partners (EPD, $26), a limited partnership that is a member of the Kiplinger Dividend 15, with a yield of 6.9%.

The energy sector is in a transition, but oil and gas are far from dead. The fact is, if you want your portfolio to reflect the U.S. and global economies, then you need energy.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. He owns none of the stocks mentioned in this column. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

Dow Rises 313 Points to Begin a Big Week: Stock Market Today

Dow Rises 313 Points to Begin a Big Week: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 is within 50 points of crossing 7,000 for the first time, and Papa Dow is lurking just below its own new all-time high.

-

DexCom, GE, SLB: Why Experts Rate These Stocks at Strong Buy

DexCom, GE, SLB: Why Experts Rate These Stocks at Strong BuyWall Street gives these three diverse names Strong Buy recommendations with high potential upside.

-

The Best Energy Stocks to Buy

The Best Energy Stocks to BuyEnergy stocks can expose investors to volatile oil and gas prices. Here's how to find the best energy stocks to buy now.

-

SLB Stock Jumps on Earnings, Dividend Hike and Buyback News

SLB Stock Jumps on Earnings, Dividend Hike and Buyback NewsSLB stock is soaring Friday after the energy firm reported strong fourth-quarter earnings and unveiled several shareholder-friendly initiatives.

-

Investing Moves to Make at the Start of the Year

Investing Moves to Make at the Start of the YearAfter another big year for stocks in 2024, investors may want to diversify in 2025. Here are five portfolio moves to make at the start of the year.

-

Stock Market Today: Markets Mark Time Ahead of Tech Earnings, Fed

Stock Market Today: Markets Mark Time Ahead of Tech Earnings, FedStocks searched for direction ahead of mega-cap tech quarterly reports and tomorrow's rate decision.

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Swing Lower as Oil Prices Retreat

Stock Market Today: Stocks Swing Lower as Oil Prices RetreatA bad-news-is-good-news jobs report sent the main indexes higher at the open, but they didn't stay there for long.

-

Stock Market Today: P&G Earnings Headline Quiet Day for Stocks

Stock Market Today: P&G Earnings Headline Quiet Day for StocksWhile the major indexes failed to make big moves today, consumer staples giant Procter & Gamble popped after earnings.