Investors, Relax About Rising Interest Rates

Rates must go substantially higher before bonds can challenge the return on stocks.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

The bond market, like the canary in a coal mine, senses when there is a change in economic activity. From the beginning of February to mid March, the yield on the ten-year Treasury bond jumped by more than a half-percentage point, signaling that traders believe the Fed’s policy of keeping short-term interest rates at record low levels may be coming to an end. With strong payroll gains and glimmers of a revival in the housing market, the case for a sustained economic recovery is strong. That means it’s unlikely the Fed will be able to maintain its near-zero rates well into 2014, as it has indicated it would do in recent policy statements.

The bottom line is that long-term rates will rise and existing bond prices will fall when the Fed formally announces that it will raise short-term rates. The price of the ten-year Treasury bond fell by about 4.6% in February and March, wiping out more than two years’ worth of interest rate payments. And although rates have since moved back down, it is only a matter of time before they rise again. This will be bad news for all the investors who piled into bond funds -- especially Treasury bond funds -- over the past five years.

Many investors worry that rising rates will also spell the end of the recent bull market in stocks, which have risen nearly 30% from their lows of last October. But you can put those fears to rest. In the past three decades, the onset of higher Fed interest rates has caused stocks to stumble at first, but it has never ended their bull run.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

For example, when the Fed began to raise rates in February 1994 following the 1990-91 recession, the market fell 9% in the next two months. But stocks quickly recovered and entered one of the longest bull markets in history. By the time the charge was over in March 2000, Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index was two-and-one-half times higher than it was when the Fed began raising rates.

Similarly, the Fed started to raise interest rates at the end of June 2004, following the 2001 recession, and the market fell 7% through August. But stocks recovered and began a bull run that culminated in October 2007.

The conventional wisdom is that rising interest rates are bad for stocks. But the Fed would not raise rates unless it anticipated a stronger economy, and that’s good for corporate profits. It’s only when a long economic expansion causes firms to hit capacity and the labor market to tighten that the Fed is forced to raise rates decisively to slow economic activity. With current unemployment above 8% and factories operating at less than 80% of capacity, the U.S. economy is nowhere near that point.

A Costly Wait

Because the market has usually stumbled when the Fed begins raising rates, you might ask whether you should wait until the Fed signals an end to its low-interest-rate policy before getting into stocks. I would answer no. I believe the Fed will begin raising rates well before the end of 2014, but stocks could be much higher than they are today when that first rate hike occurs. So waiting could cost you an opportunity.

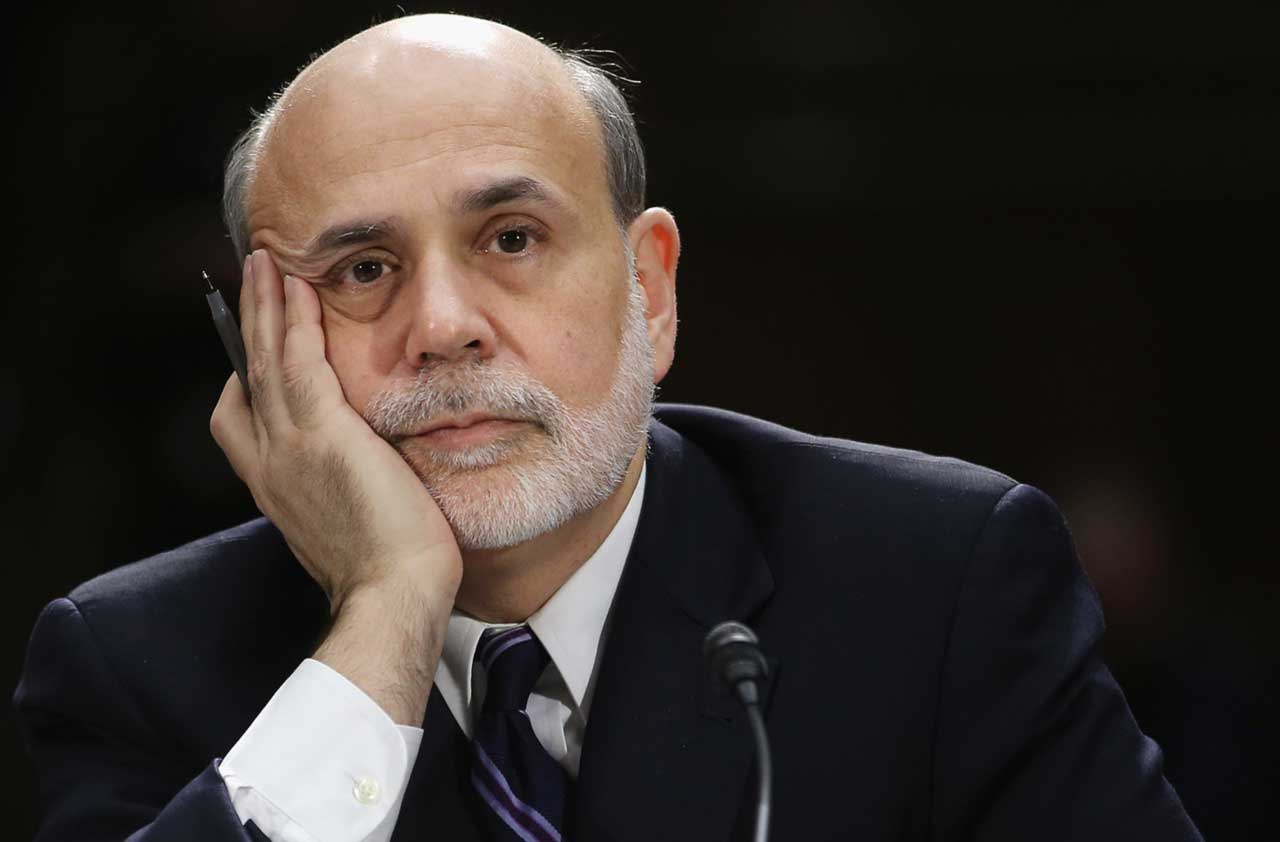

Furthermore, Fed chairman Ben Bernanke is committed to being more open about the Fed’s interest rate intentions than was his predecessor, Alan Greenspan. So Bernanke will likely indicate that the Fed is ready to shift gears well in advance of the first rate hike, giving the markets plenty of time to adjust.

Investors should view the increase in Treasury yields as a herald of better times to come, not as a development that will end the bull market in stocks. Today, U.S. stocks are trading at 13 times estimated 2012 earnings. That is well below the average of 19 that prevailed in low- and moderate-interest-rate environments over the past 50 years.

Columnist Jeremy J. Siegel is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and the author of Stocks for the Long Run and The Future for Investors.

ORDER NOW: Buy Kiplinger’s Mutual Funds 2012 special issue for in-depth guidance on the only investments you need.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

A Preview of the Fed Under Trump

A Preview of the Fed Under TrumpEconomic Forecasts John Taylor, a former Treasury official in the Bush administration, is a top candidate to replace Fed chair Janet Yellen.

-

Investors, Don't Fear Higher Rates

Investors, Don't Fear Higher Ratesinvesting Although interest rates will rise modestly in coming months, that should not derail the bull market.

-

Why Investors Shouldn't Be Afraid of Inflation

Why Investors Shouldn't Be Afraid of InflationEconomic Forecasts An inflation rate of 2% to 3% is good for stocks because it gives companies the power to raise prices, which helps boost profits.

-

A Positive Outlook for U.S. Interest Rates

A Positive Outlook for U.S. Interest RatesEconomic Forecasts Instead of the threat of deflation from weak growth and falling prices, the U.S. is facing the opposite: accelerating inflation.

-

Can the Fed Save the Stock Market?

Can the Fed Save the Stock Market?Markets In retrospect, it was ill-timed for the Federal Reserve to start hiking short-term interest rates. But that can easily be fixed.

-

Bernanke's Ultimate Legacy

Bernanke's Ultimate Legacyinvesting The former Fed chairman's decisions in 2008 were an act of courage that averted an economic collapse far worse than we experienced.

-

Worries About China’s Economy Are Overblown

Worries About China’s Economy Are OverblownEconomic Forecasts Among the consequences of China's slowdown: lower commodity prices, which actually benefit the U.S.

-

Surviving the Greek Financial Crisis

Surviving the Greek Financial CrisisEconomic Forecasts Despite the recent friction, I believe the eurozone is stronger after putting down the Greek rebellion.