The Bears Are Wrong About the Economy

Don't sweat all the talk of gloom and doom; history proves that, in the long run, it doesn't pay to be a pessimist.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

In August 1979, Business Week magazine ran a cover story entitled "The Death of Equities," in which it declared that inflation had permanently crippled stocks as an investment. "For better or for worse," Business Week asserted, the U.S. "probably has to regard the death of equities as a near-permanent condition -- reversible some day, but not soon."

Yet just two months later, Paul Volcker, newly appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve, put the screws on inflation by sharply raising short-term interest rates and cutting back on growth of the money supply. The economy suffered two recessions in the next three years, but stocks held their value. In the summer of 1982, stocks kicked off the greatest bull market the world has ever seen. During the next 18 years, Standard & Poor's 500-stock index rose nearly 15-fold, or 19.9% per year, creating trillions of dollars in wealth for investors who owned stocks.

Pessimism is as rampant today as it was in 1979 and, once again, it is misplaced. The specter of inflation has been replaced by fear of a trio of other dire prospects: deflation and financial collapse, the long and painful unwinding of an economy that has gorged on borrowed money, and the prospect of millions of baby-boomers selling their stocks to finance an increasingly bleak future. Last June, for example, the Royal Bank of Scotland declared that the world economy was at the "cliff-edge," and predicted that a dramatic economic collapse would "destroy the world's worst cult -- the cult of the equity, which has no basis in fact, or history."

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Then we have Pimco's Bill Gross, manager of the world's largest bond fund, who, with Pimco chief executive Mohamed El-Erian, coined the term "new normal" to describe an economy characterized by slow growth, weakened consumers and meager stock returns. Further adding to the gloom are statements by Harry Dent, who in 1993 wrote The Great Boom Ahead, a book with an optimistic stock-market outlook based on demographic changes. Now Dent predicts that the impending retirement of the baby-boom generation will lead to a massive economic and financial bust.

But all these doomsayers exhibit the same shortsightedness that Business Week did three decades earlier. The Royal Bank of Scotland's claim that the "cult of the equity" has "no basis in fact" is just plain wrong. I documented the remarkable long-term returns in the U.S. stock market in Stocks for the Long Run. In Triumph of the Optimists, three British researchers calculated returns on stocks, bonds and government securities in 16 countries over the past century. Their conclusion was unambiguous: Stock returns beat bonds in every country by a wide margin.

Bill Gross's new normal is similarly shortsighted. Gross asserts that consumers, who account for the biggest chunk of economic growth, are burdened with debt and tapped out. As a result, he says, weak consumer spending will doom the economy to slow growth for many years. But long-term economic growth depends on productivity growth, not on the debt load of consumers. In fact, productivity growth has been accelerating over the past decade, averaging 2.7% per year, or 0.5 percentage point above its long-term average. In the past this growth has generated the income necessary to propel the economy forward, and it will do so again.

Finally, predictions warning that the wave of baby-boomers entering retirement will lead to the liquidation of stocks and a collapse of values are similarly flawed. Emerging economies account for 85% of the world's population. My research has found that rising incomes in Asia and elsewhere can generate enough savings to absorb the boomers' asset sales without significantly depressing prices.

History shows that pessimists, no matter how fashionable, have always been wrong about long-term prospects for the U.S. economy and the stock market. This time is no different.

Columnist Jeremy J. Siegel is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School and the author of Stocks for the Long Run and The Future for Investors.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

A Preview of the Fed Under Trump

A Preview of the Fed Under TrumpEconomic Forecasts John Taylor, a former Treasury official in the Bush administration, is a top candidate to replace Fed chair Janet Yellen.

-

Investors, Don't Fear Higher Rates

Investors, Don't Fear Higher Ratesinvesting Although interest rates will rise modestly in coming months, that should not derail the bull market.

-

Why Investors Shouldn't Be Afraid of Inflation

Why Investors Shouldn't Be Afraid of InflationEconomic Forecasts An inflation rate of 2% to 3% is good for stocks because it gives companies the power to raise prices, which helps boost profits.

-

A Positive Outlook for U.S. Interest Rates

A Positive Outlook for U.S. Interest RatesEconomic Forecasts Instead of the threat of deflation from weak growth and falling prices, the U.S. is facing the opposite: accelerating inflation.

-

Can the Fed Save the Stock Market?

Can the Fed Save the Stock Market?Markets In retrospect, it was ill-timed for the Federal Reserve to start hiking short-term interest rates. But that can easily be fixed.

-

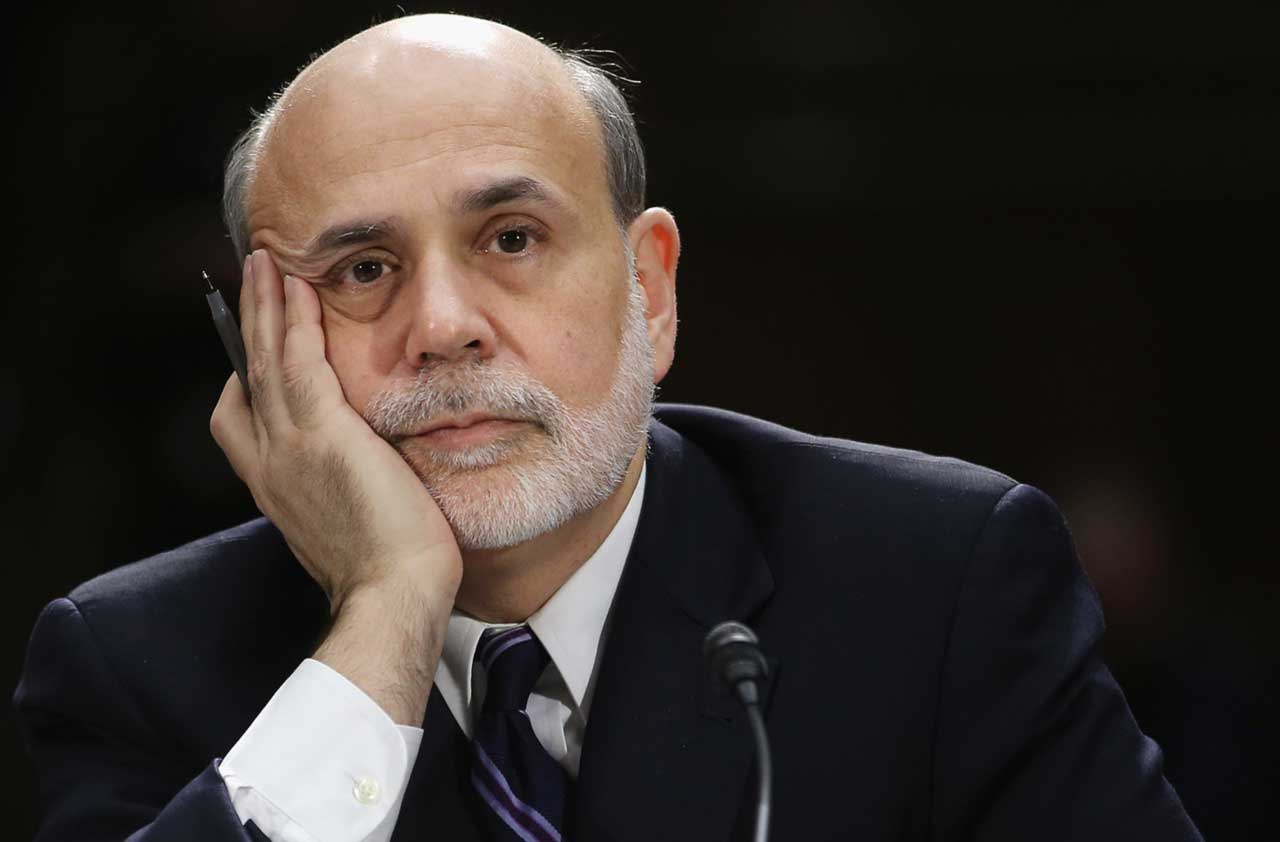

Bernanke's Ultimate Legacy

Bernanke's Ultimate Legacyinvesting The former Fed chairman's decisions in 2008 were an act of courage that averted an economic collapse far worse than we experienced.

-

Worries About China’s Economy Are Overblown

Worries About China’s Economy Are OverblownEconomic Forecasts Among the consequences of China's slowdown: lower commodity prices, which actually benefit the U.S.

-

Surviving the Greek Financial Crisis

Surviving the Greek Financial CrisisEconomic Forecasts Despite the recent friction, I believe the eurozone is stronger after putting down the Greek rebellion.