Is the Bull Market Over?

With today's low interest rates, it makes sense that price-earnings ratios should be higher than average.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

My friend Robert Shiller recently accepted a well-deserved Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his work on understanding volatility in the financial markets. Shiller has also devised an indicator for determining whether the stock market is cheap or expensive called the CAPE ratio, short for cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio.

In calculating the market’s P/E, the standard practice is to divide the price of Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index by either the previous 12 months’ earnings for the companies in the index or analysts’ estimates of earnings over the next 12 months. But the CAPE ratio substitutes the index’s average earnings over the preceding ten years. Shiller’s rationale: Using a long-term average of past earnings reduces the likelihood that the peaks and troughs of the business cycle will lead to the use of abnormally high or low earnings in calculating the P/E.

Over time, the CAPE ratio has proved to be an accurate predictor of stock returns. Forecasts generated by the CAPE ratio have generally been very similar to those resulting from standard P/E methodology. For example, in early 2000 at the top of the tech bubble, both ratios indicated that the stock market was overvalued.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

But in recent years, predictions based on each of these two ratios have diverged. The CAPE ratio recently stood more than 50% above its long-term average and presented a bearish picture of future stock returns. Traditional P/E calculations using current and forecast earnings, however, showed that the market is trading close to its average historical valuation. Which is correct?

A record fall-off. My studies indicate one reason that the CAPE ratio appears to be so bearish. Reported earnings of the S&P 500 (used by Shiller to calculate the CAPE ratio) fell a record 92% in the 12 months ended in March 2009. In fact, in the fourth quarter of 2008, S&P 500 earnings were negative for the first time in the history of the index. This sharply reduced the ten-year average and set the CAPE ratio well above its historical level. It won’t be until 2020 that the earnings depression caused by the Great Recession is no longer reflected in the ten-year average, restoring the CAPE to more-normal levels.

A more significant explanation is that over the past two decades, the method of computing the S&P 500’s reported earnings series has changed dramatically. Firms are now required to write down assets that have lost value and include those losses in reported earnings, regardless of whether the asset was sold. But firms cannot “write up” appreciated assets unless they are sold. As a result, earnings declines in the 2001 recession, and particularly in the most recent downturn, were much more severe than in any previous economic contraction.

In contrast to the S&P earnings series, corporate profits as measured by the National Income and Product Accounts did not turn negative in the fourth quarter of 2008. Furthermore, the maximum decline in 12-month earnings was 22% instead of 92%. When NIPA profits are substituted for S&P reported earnings, the CAPE ratio is only about 10% to 15% above its long-term average—not statistically meaningful.

None of this should detract from CAPE’s attractiveness. But it’s important to use a data series that has been consistently generated over the years, such as the NIPA figures. Even when the data has been collected consistently, investors should be mindful that the correct P/E for the market is not necessarily its long-term average. For instance, with today’s low interest rates, it makes sense that P/Es should be higher than average. I believe the current bull market is not over, and any correction will prove to be a buying opportunity.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

A Preview of the Fed Under Trump

A Preview of the Fed Under TrumpEconomic Forecasts John Taylor, a former Treasury official in the Bush administration, is a top candidate to replace Fed chair Janet Yellen.

-

Investors, Don't Fear Higher Rates

Investors, Don't Fear Higher Ratesinvesting Although interest rates will rise modestly in coming months, that should not derail the bull market.

-

Why Investors Shouldn't Be Afraid of Inflation

Why Investors Shouldn't Be Afraid of InflationEconomic Forecasts An inflation rate of 2% to 3% is good for stocks because it gives companies the power to raise prices, which helps boost profits.

-

A Positive Outlook for U.S. Interest Rates

A Positive Outlook for U.S. Interest RatesEconomic Forecasts Instead of the threat of deflation from weak growth and falling prices, the U.S. is facing the opposite: accelerating inflation.

-

Can the Fed Save the Stock Market?

Can the Fed Save the Stock Market?Markets In retrospect, it was ill-timed for the Federal Reserve to start hiking short-term interest rates. But that can easily be fixed.

-

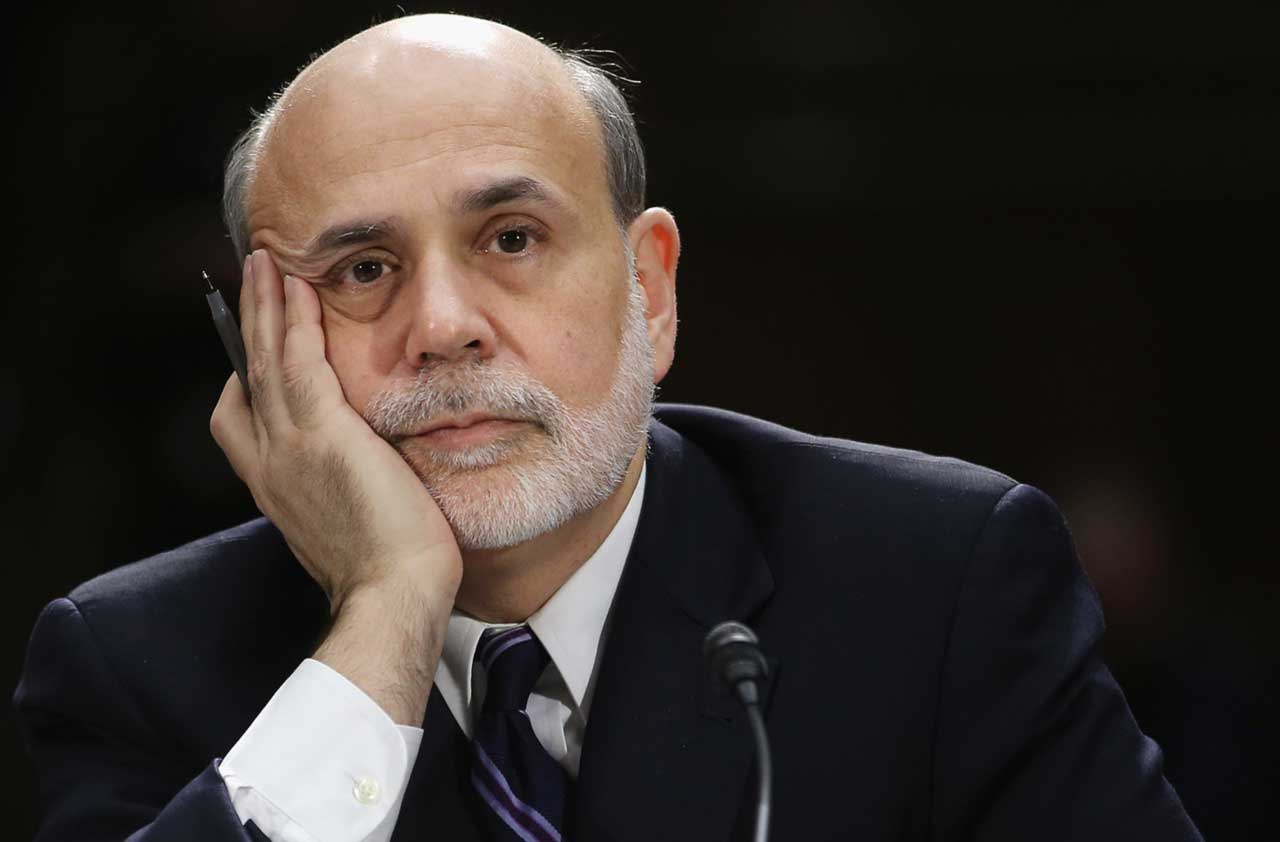

Bernanke's Ultimate Legacy

Bernanke's Ultimate Legacyinvesting The former Fed chairman's decisions in 2008 were an act of courage that averted an economic collapse far worse than we experienced.

-

Worries About China’s Economy Are Overblown

Worries About China’s Economy Are OverblownEconomic Forecasts Among the consequences of China's slowdown: lower commodity prices, which actually benefit the U.S.

-

Surviving the Greek Financial Crisis

Surviving the Greek Financial CrisisEconomic Forecasts Despite the recent friction, I believe the eurozone is stronger after putting down the Greek rebellion.