Why Is My Portfolio Lagging? Blame It on 2015

A portfolio without FANGs was doomed to have trouble last year.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

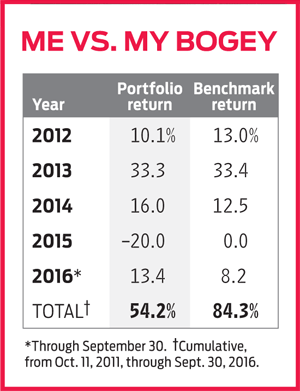

In my previous column, I acknowledged, with much chagrin, that my Practical Investing portfolio had badly lagged its benchmark, Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (symbol VTI), since I launched it in October 2011. However, the portfolio is trouncing its bogey so far in 2016, and for much of its history it has run neck and neck with the fund. And that made me wonder where—or when—I went wrong. So I decided to take a deeper dive into the portfolio’s performance.

What happened in 2015? In simple terms, a small group of large-company growth stocks performed spectacularly, masking the much weaker performance of the broad market. The most noteworthy of last year’s super-stocks were the FANGs: Facebook (which gained 34% in 2015), Amazon.com (118%), Netflix (135%) and Google (47%), now called Alphabet. I couldn’t bring myself to buy any of the FANGs. Nor did I own two other supernovas: interactive game developer Activision Blizzard (up 92%) or Nvidia Corp. (64%), a maker of graphics processors.

I’ve shied away from all of these stocks for two reasons: First, although all are great companies with superior prospects and are perfect for growth-oriented investors, their valuations are uncomfortably rich for a value investor like me. And I’ve avoided some of the FANGs specifically because of concerns that management doesn’t treat shareholders fairly. Alphabet, Amazon and Facebook have two-tier stock-ownership structures that seek to keep voting control of the companies in the hands of their founders. The scintillating gains of these stocks are proof positive that disenfranchising shareholders does not necessarily hurt results. However, I view firms with dual voting classes much as I do benevolent dictatorships: You don’t really know when things may become less benevolent. So I generally steer clear of them.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Unfortunately for me, few energy companies treat shareholders in similar fashion. So I had no grounds, on the basis of this corporate-governance issue, to avoid Chevron and Stone Energy, which I held in 2015. And I owned Dover Corp., an industrial firm that makes, among other things, oil drilling and production equipment. All three stocks plunged last year, along with oil prices, and have yet to fully recover.

I bought the stocks thinking that even if crude prices bounced around over the short term, oil is so vital to our economy that the companies would thrive over the long haul. I still believe that to be true. That said, I sold my Stone shares late last year because of my concern that the small producer could run out of cash. And I unloaded the other two this past summer because I realized that I was, at best, ambivalent about the recovery of oil prices and, more generally, about investing in companies tied to carbon-based energy.

Why? Even as my portfolio was struggling, I was spending $17,000 to put solar panels on my house. The math suggested that I wouldn’t break even for at least seven years—not exactly a brilliant return on my investment. Yet I bought the solar panels because I’d love to live in a world that relies on sustainable and nonpolluting sources of energy. It felt a little hypocritical to do that and still root for Chevron (Go, Big Oil!). I do think Chevron, the nation’s second-biggest energy company, will eventually come back. And the stock, at $103, yields a generous 4.2%. But I didn’t want to question my life goals every time I looked at the portfolio, so Chevron and Dover had to go. Sometimes investing is more about emotion than logic. This was one of those times.

See Also from Kiplinger: 10 Great Stocks for the Next 10 Years

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)State Taxes Living in one of these places could lower your 2025 investment taxes — especially if you invest in real estate.

-

The Final Countdown for Retirees with Investment Income

The Final Countdown for Retirees with Investment IncomeRetirement Tax Don’t assume Social Security withholding is enough. Some retirement income may require a quarterly estimated tax payment by the September 15 deadline.

-

How to Beef Up Your Portfolio Against Inflation

How to Beef Up Your Portfolio Against Inflationinvesting These sectors are better positioned to benefit from rising prices.

-

Taxable or Tax-Deferred Account: How to Pick

Taxable or Tax-Deferred Account: How to PickInvesting for Income Use our guide to decide which assets belong in a taxable account and which go into a tax-advantaged account.

-

Smart Investing in a Bear Market

Smart Investing in a Bear Marketinvesting Here's how to make the most of today’s dicey market.

-

How to Open a Stock Market Account

How to Open a Stock Market Accountinvesting Investing can be fun, but you need a brokerage account to do it. Fortunately, it’s easy to get started.

-

The Right Dividend Stock Fund for You

The Right Dividend Stock Fund for YouBecoming an Investor Dividend stock strategies come in many different flavors. Here's what to look for.

-

Alternative Investments for the Rest of Us

Alternative Investments for the Rest of UsFinancial Planning These portfolio diversifiers aren't just for the wealthy.