How to Prepare Your Bond Portfolio for Rising Rates

The Fed has held rates artificially low for years. Bond investors need to prepare for their inevitable rise.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Since 2009, short- and long-term interest rates have hit historic lows. But why? Was the economy great? Was there a huge demand for bonds? Was there a fundamental reason for rates to be so low?

The simple answer to these questions is "no." In fact, just the opposite was true. But what does this mean to investors?

Simply put, interest is the cost of money, plus a premium for risk. If a solid company wants to borrow money, the interest rate would be low due to the low risk. But if your good-for-nothing brother-in-law wants to borrow money, if he can find anybody to loan it to him, the rate would be very high due to the high risk.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

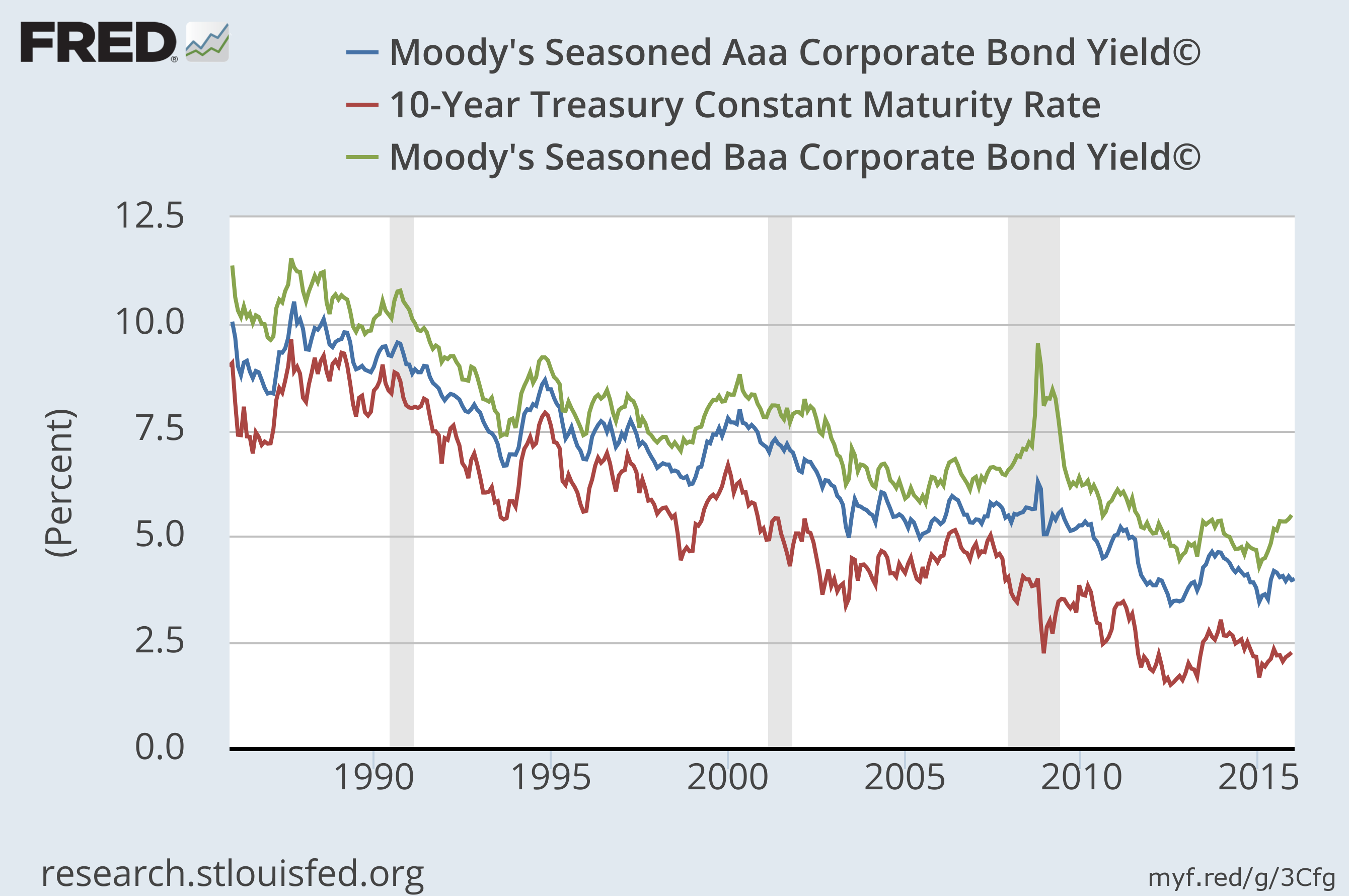

Generally, various interest rates move in tandem, but with a spread in between them to compensate for the risk. U.S. Treasuries generally are considered the lowest risk while junk bonds could be very high risk.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) controls short-term (ST) interest rates through the Fed Funds Rate. They raise rates to slow the economy and prevent inflation. They lower rates to give the economy a boost. Since 2009, they have been in boost mode, keeping ST rates near zero. Yet the economy has barely moved along.

So the Fed attacked long-term (LT) rates. Normally, LT rates are controlled by the markets. More buyers means rates go down; more sellers, rates go up. But the Fed stepped in and became the primary buyer of Treasury bonds through its quantitative easing programs. This added a huge amount of buying pressure, pushing LT rates artificially lower.

Yet the economy still didn't catch fire. Why?

The Fed's theory on low rates is that borrowers (corporate and individual) will want to borrow money if rates are low. This is true. Who doesn't want to pay lower rates on their debt? This borrowing would spur the economy onward as companies invested in upgrading equipment, expanding facilities and spending on inventory. Individuals would buy more homes, spend more on credit cards and keep the retail side humming. The Fed would get the result it was looking for: self-sustained economic growth.

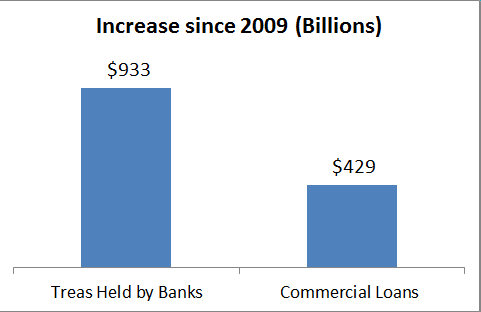

What they failed to realize was that lenders do not want to lend when rates are low. Lenders have to be compensated for the risks they take. This rate is normally determined by the market. But since the Fed has forced long-term and short-term rates artificially low, lenders are not being compensated properly for the risk they are taking making loans. So instead of making loans to companies, many banks have found other things to do with their money. Below is a chart comparing some of what banks have done with their money since 2009.

According to Federal Reserve Data, banks have loaned $429 billion in net new commercial loans (that might be given to businesses for factory expansions or new equipment, for example). But they have loaned more than double that number, $933 billion, to the government by buying Treasury bonds. It appears that banks have determined that the low rates and low risk they get from Treasury bonds is a better bet than making loans. How much more economic growth might there have been if banks had been making loans instead of buying Treasuries?

Ironically, rates need to rise substantially for lenders to start lending again. It may seem counterintuitive, but if the Fed wants economic growth, rates need to be much higher. Unfortunately, to get to the point of rates being high enough for lenders to be properly compensated, the bond market would likely have to go through a severe bear market.

Instead, the Fed is kicking the tires on negative interest rates. Janet Yellen, the Fed chair, discussed the possibility at her recent Congressional testimony. Yes, the thinking seems to be: "Zero interest rates didn't get the economy going, but maybe negative interest rates will!"

Japan went negative a few months ago, and several countries in Europe and the Eurozone are already negative, too. In those countries, banks charge a fee for savings and checking accounts instead of paying interest. Some short-term investments do not earn any interest.

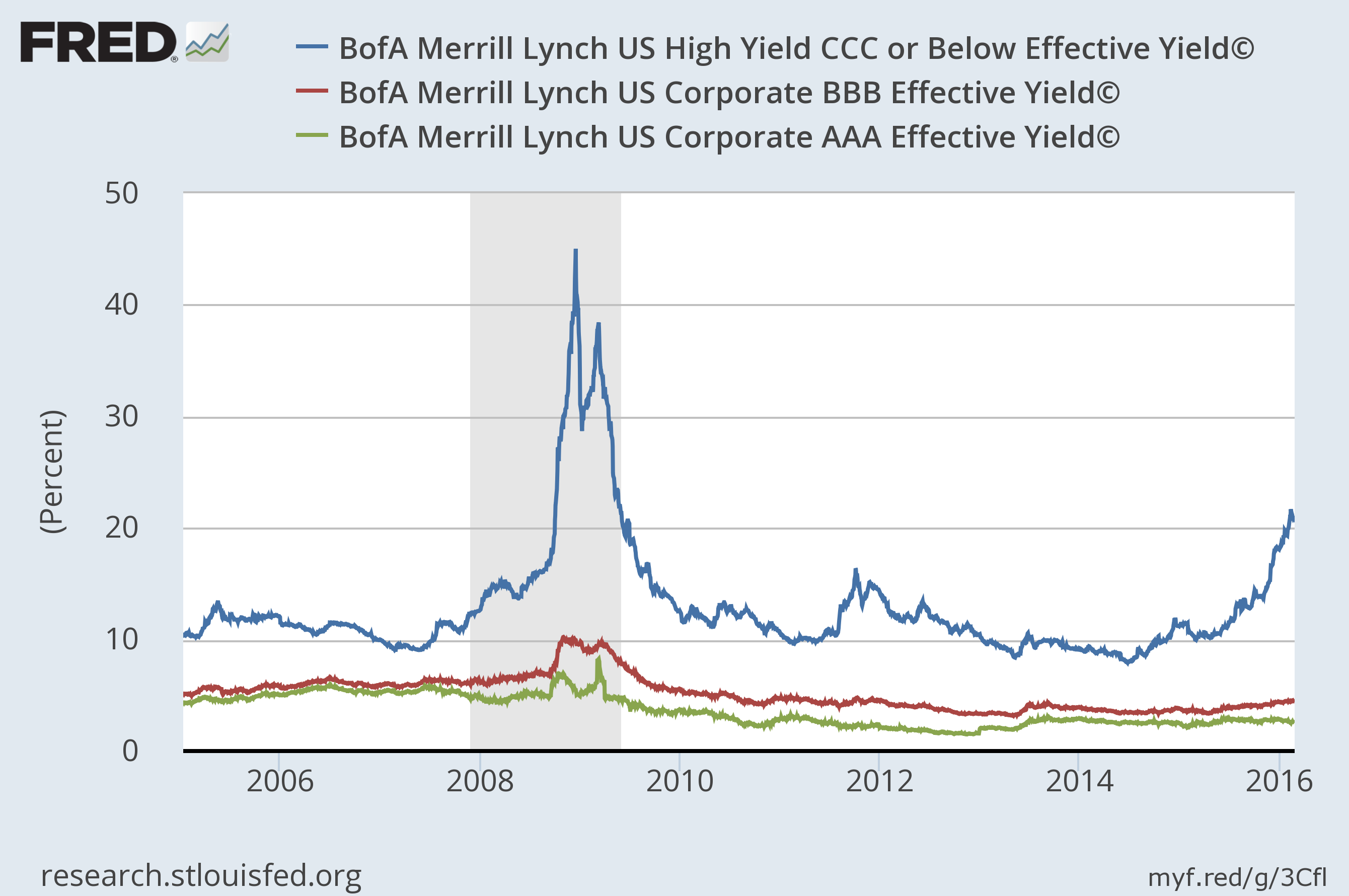

However, negative interest rates in the U.S. may accidentally push some rates higher. As you can see in the chart below, rates on lower-quality corporate bonds are rising while rates on higher-quality bonds are declining. This is a rare occurrence.

The last time rates on low-quality (CCC-rated) bonds rose the way they are moving today was during the 2008 collapse. It is our belief that if ST rates go negative, the link between bond markets could break. Rates on high-quality bonds, including Treasuries, could continue drifting lower while rates on low-quality corporates could head much higher.

Even worse, since rates on low-quality corporates are already rising, if the economy does slow further, better-quality corporates could come under pressure as well. A unique situation could arise in which the Treasury bond market is stable while the corporate bond market falls into a bear market.

So what does this mean? Rates have been held artificially low for years. Bond prices therefore are artificially high. Eventually, rates will rise to historical norms, and bond prices will fall. Whether that happens quickly or slowly is anybody's guess. Throw in the potential for negative short-term rates, and the bond markets could be a real mess.

This current Fed hasn't shown that it fully understands the ramifications of its actions. Its zero interest rate policy has painted it into a corner from which it seems unable to escape. Somebody once said, "If you find yourself in a hole, stop digging." The Fed doesn't understand that and may want to keep digging with negative rates.

What should investors do about all this? Look at your bond holdings, especially within your mutual funds. Determine the types of bonds you hold, the risks involved with and if you are comfortable with those risks. As the bond market reacts to rising rates and declining profits in the oil patch, high-yielding bonds with low ratings could be the worst risks.

Bond corrections can happen fast, so reducing risks while prices are still high is a good idea. Forget that what you shift into may have a lower yield currently. At this point, bond investors should be concerned more about the return of their money than the return on their money.

See Also: The Truth About the Last Bull Market

(Editor's Note: For a different take on bonds, read Kiplinger's Investing for Income editor Jeff Kosnett's recent column, Focus on Quality, Not the Fed.)

John Riley, registered Research Analyst and the Chief Investment Strategist at CIS, has been defending his clients from the surprises Wall Street misses since 1999.

Disclosure: Third party posts do not reflect the views of Cantella & Co Inc. or Cornerstone Investment Services, LLC. Any links to third party sites are believed to be reliable but have not been independently reviewed by Cantella & Co. Inc or Cornerstone Investment Services, LLC. Securities offered through Cantella & Co., Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. Advisory Services offered through Cornerstone Investment Services, LLC's RIA. Please refer to my website for states in which I am registered.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

In 1999, John Riley established Cornerstone Investment Services to offer investors an alternative to Wall Street. He is unique among financial advisers for having passed the Series 86 and 87 exams to become a registered Research Analyst. Since breaking free of the crowd, John has been able to manage clients' money in a way that prepares them for the trends he sees in the markets and the surprises Wall Street misses.