How Can I Estimate the Income I'll Need in Retirement?

It's an important question, and the answer starts with a simple rule of thumb. With a little personalization, this income replacement metric can be a useful tool.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

How much money do you make? That’s a fairly easy question.

OK, now how much money do you spend? That one’s a little tougher. What exactly counts as spending? Are we including taxes? If you’re paying down a mortgage, is the principal portion considered spending? What about your kid’s tuition payment from the 529 account?

As you can see, it’s usually easier to think about your money in terms of your income rather than your spending. That’s why your income replacement rate — the percentage of your preretirement income before taxes that you’ll need to support your lifestyle in retirement — can be a useful planning tool.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

This simple metric, which doesn’t require you to do any tricky tax calculations, may help you put your retirement finances into clearer context. The key to making this percentage useful is to estimate it with your specific financial situation in mind.

First, for a general rule of thumb, start with 75%

After analyzing many scenarios, we found that a 75% replacement rate may be a good starting point to consider for your income replacement rate. This means that if you make $100,000 shortly before retirement, you can start planning using the ballpark expectation that you’ll need about $75,000 a year to live on in retirement.

Why would you likely need less income in retirement than during your working years? Typically, it’s because:

- Most people spend less in retirement. (For more on that, read 10 Things You’ll Spend Less on in Retirement.)

- Some of your income during your working years went toward saving for retirement, which isn’t necessary anymore.

- Your taxes will likely be lower — especially payroll taxes, but probably income taxes as well.

The 75% income replacement rate ballpark figure is based on reducing your spending at retirement by 5% and saving 8% of your gross household income during your working years. We chose 8% because it’s about the average that people are saving in their retirement accounts.

Then tailor that rule of thumb to fit your own needs

There are several reasons the 75% starting point may not be right for you. First, the initial savings and spending assumptions may not be appropriate. For example, you may be saving closer to the 15% we recommend for retirement. Fortunately, our analysis found that this is a pretty easy adjustment to make. Every extra percentage point of savings beyond 8%, or spending reduction beyond 5%, reduces your income replacement rate by about 1 percentage point. Think of these adjustments as a nearly one-to-one ratio.

So, if you’re saving 12% of your income instead of the 8% we assumed, take your replacement rate of 75% and subtract 4 percentage points, resulting in a personally adjusted estimate of around 71%.

Next, the way you’ve saved for retirement also affects the replacement rate. The 75% starting point assumes all savings are pretax — like a traditional 401(k) or IRA. That’s a conservative assumption, since you’re fully taxed on those assets when you withdraw them. Saving with a Roth account, on the other hand, is after tax and can generate tax-free income, which means if you have a large proportion of your retirement savings in Roth accounts, your income replacement rate should be lower.

Third, your marital status and household income are two factors that affect Social Security benefits and your tax situation. Those two factors, in turn, affect your income replacement rate. The 75% starting point reflects a household earning around $100,000 to $150,000 before retirement.

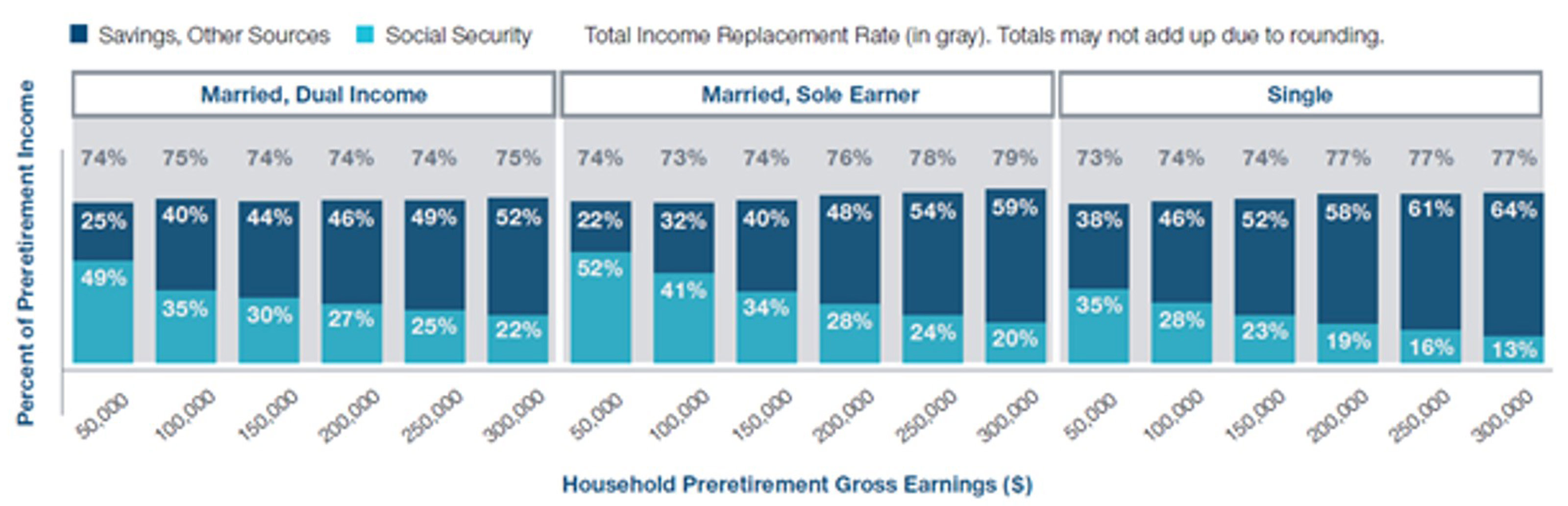

To sum it all up, you can check the chart below for a good starting point, then make some adjustments based on the parameters above.

Source: T. Rowe Price, Income Replacement in Retirement.

Assumptions: The household’s income and spending keep pace with inflation until retirement, and then spending is reduced by 5%. Spouses are the same age, and “dual income” means that the one spouse generates 75% of the income that the other spouse earns. Federal taxes are based on rates as of January 1, 2022. While rates are scheduled to revert to pre-2018 levels after 2025, those rates are not reflected in these calculations. The household uses the standard deduction, files jointly (if married), and is not affected by alternative minimum tax or any tax credits. The household saves 8% of its gross income, all pretax. Federal income tax in retirement assumes all income is taxed at ordinary rates and reflects the phase-in of Social Security benefit taxation. State taxes are a flat 4% of income after pretax savings and are not assessed on Social Security income. Social Security benefits are based on the SSA.gov Quick Calculator (claiming at full retirement age), which includes an assumed earnings history pattern.

Now you can use the replacement rate to help you plan

You’ll notice that the chart breaks down the replacement rate into income sources. Understanding the income you’ll need from sources other than Social Security can help you estimate a savings level to aim for before you retire.

At higher income levels, the net effect is that Social Security benefits make up a much smaller percentage of the total income replacement rate — meaning more savings or other income sources would be needed to fund retirement.

A practical example

Suppose you’re single and earn $100,000 a year before taxes. To keep it simple, let’s say our assumptions seem mostly reasonable to you. Based on the graph above, you should plan to replace around 74%, or $74,000, of that income. Let’s then assume you expect $28,000 of annual Social Security benefits, in which case you’ll need about $46,000 of gross income from other sources.

To find out how much you might need to save for retirement, you can work backward from there. If you’re comfortable with a 4% initial withdrawal rate on your assets, then you should aim for a $1.15 million nest egg. (To arrive at that figure, we took $46,000 and divided by 0.04.) That’s in today’s dollars, so you’ll want to bump that up for inflation, especially if you’re a long way from retirement.

Another way to think of it — for this example — is to aim to save an amount equal to about 11.5 times your income just before retirement: $100,000 times 11.5 equals $1.15 million. We recommend that most people consider a target of between seven and 13.5 times their ending salary.

The replacement rate is just the beginning

There’s no “right” number that works for everyone, and your situation can change over time. As you approach retirement, it will be important for you to assess your spending needs more carefully. But for someone several years from retirement, the income replacement rate — which is based on estimated spending — can be a helpful guide.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Roger Young is Vice President and senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price Associates in Owings Mills, Md. Roger draws upon his previous experience as a financial adviser to share practical insights on retirement and personal finance topics of interest to individuals and advisers. He has master's degrees from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Maryland, as well as a BBA in accounting from Loyola College (Md.).

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're Rich

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're RichSome frugal habits are worth it, no matter what tax bracket you're in.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.

-

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look Like

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look LikeThis is when you should be shifting your focus from growing your portfolio to designing an income and tax strategy that aligns your resources with your purpose.

-

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your Stress

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your StressTo be confident about retirement, consider building a safety net by dividing assets into distinct layers and establishing a regular review process. Here's how.

-

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)The key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)Couples who talk openly about finances, including estate planning, are more likely to head into retirement joyfully. How can you get the conversation going?

-

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan: Don't Leave Your Best Friend to Chance

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan: Don't Leave Your Best Friend to ChanceAdding a pet trust to your estate plan can ensure your pets are properly looked after when you're no longer able to care for them. This is how to go about it.

-

Want to Avoid Leaving Chaos in Your Wake? Don't Leave Behind an Outdated Estate Plan

Want to Avoid Leaving Chaos in Your Wake? Don't Leave Behind an Outdated Estate PlanAn outdated or incomplete estate plan could cause confusion for those handling your affairs at a difficult time. This guide highlights what to update and when.

-

I'm a Financial Adviser: This Is Why I Became an Advocate for Fee-Only Financial Advice

I'm a Financial Adviser: This Is Why I Became an Advocate for Fee-Only Financial AdviceCan financial advisers who earn commissions on product sales give clients the best advice? For one professional, changing track was the clear choice.