What to Do If You Have to Retire Early

Life throws you a curveball, and you end up leaving the workforce earlier than planned. Here’s what to do next.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

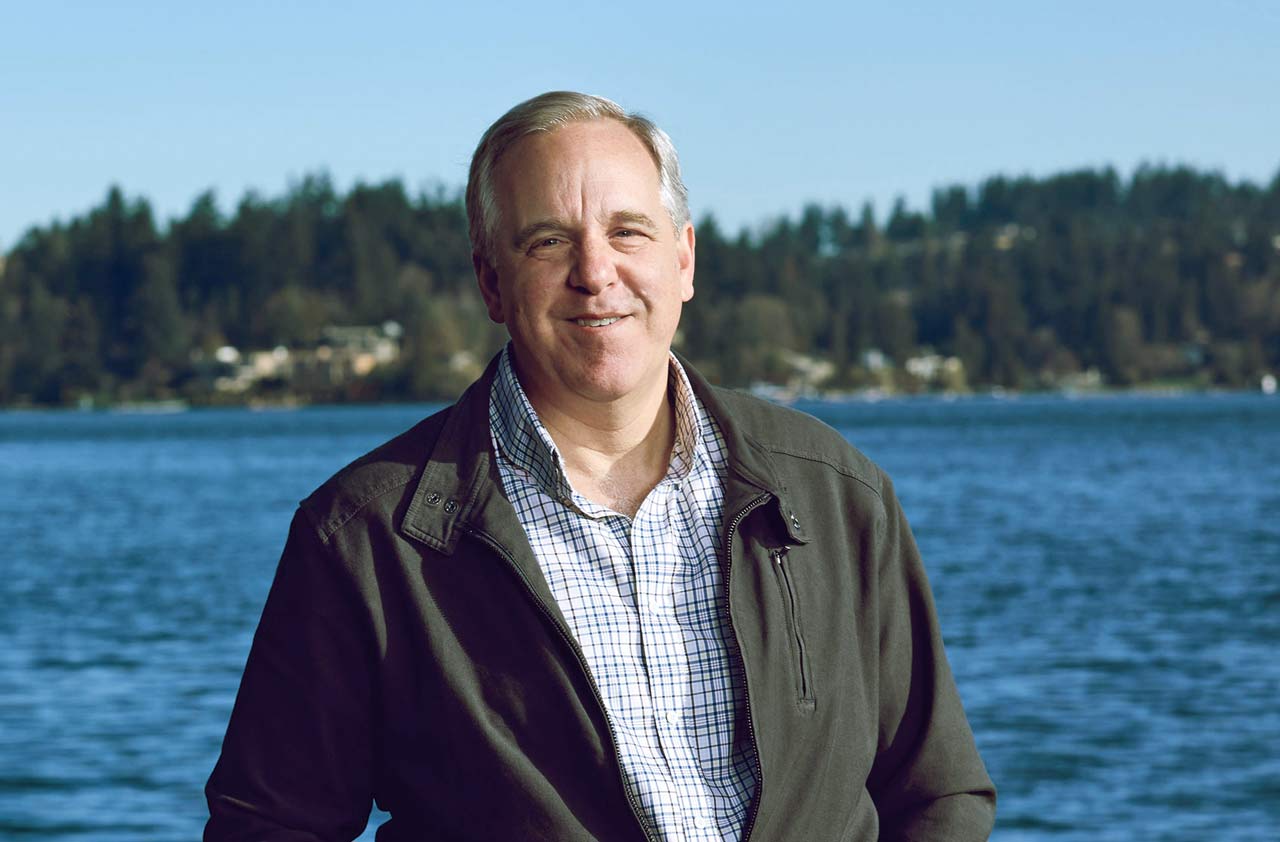

Early in his career, Drew Parker’s goal was to retire at age 57—or at least be financially prepared to quit working by then. But three years ago, at age 55, his retirement came sooner than expected when his employer, Nordstrom, restructured and offered him a buyout.

Parker, of Mercer Island, Wash., says he took the buyout because he believed it might be the last time the retailer offered severance packages with job cuts. He left Nordstrom, where he had worked for 16 years, with about six months’ salary and hunted for another job.

“I gave it a good effort, but I got almost no responses,” says Parker, who had been a merchandise financial manager, working with Nordstrom’s buyers. “In this area, the competition is tough, and at my age, it was much tougher.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Like Parker, many older workers find themselves suddenly retired—sometimes years ahead of their target date. According to a 2018 survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute, nearly one-third of workers predict they will remain in the workforce until age 70 or older, and only 10% expect to retire before 60. But in reality, only 7% of retirees surveyed stayed on the job until at least 70, and more than one-third had quit working before age 60. Many end up retiring early because of a job loss, a health problem or caregiving responsibilities.

“It happens more often than people realize,” says James Bayard, a certified financial planner in Baton Rouge, La. “Given that it does happen, everyone should have a preliminary plan for it.”

Take a deep breath. When retirement comes unexpectedly, the initial impulse is often to make drastic financial moves that could have adverse repercussions, financial planners say. For example, draining a 401(k) will trigger taxes and, depending on your age, early-withdrawal penalties.

If you work with a financial adviser, ask your planner to run the numbers to see where you stand and advise you of your options. If you’re a do-it-yourselfer, your first step should be to set up a budget based on your new circumstances. Review your sources of income, such as a pension, savings, severance or investments. Next, look at your expenses, how they’ll change now that you’re not working and whether you need to cut them. Online budgeting tools such as Mint.com and PersonalCapital.com can help.

In Parker’s case, his wife continues to work at Nordstrom as a business process manager. “The question was: Could we live on one salary when we had always lived on two?” he says. For them, the answer was yes. Some expenses disappeared or shrank. For instance, paying for yard maintenance and child care for the Parkers’ 12-year-old son was no longer necessary. Auto insurance became less expensive because one of the family’s cars was being driven less. Parker no longer saves for retirement, but his wife continues to, in addition to putting money aside each month in a 529 college-savings plan for their son.

Consider part-time work. Even if your full-time job is no more, consider finding a part-time gig to bring in some money. Every dollar you earn is one less that you’ll have to pull from savings and investments. “It might make the difference between what makes a plan work or not work,” says Steven Novack, a financial adviser in New York City. Some part-time jobs even come with benefits. Costco and Starbucks, for instance, offer part-timers health insurance and 401(k) plans with a company match.

For some people, a job loss can also be an opportunity to become your own boss. Parker markets a financial-planning tool called The Complete Retirement Planner. He had developed a spreadsheet to track his finances in retirement and show how they would change if, for example, he took Social Security early or his wife lost her job. Friends wanted to use it, too, so he added more scenarios to fit others and started selling it online in mid 2017.

Tap accounts to minimize taxes. If income from part-time work or a spouse’s job isn’t enough—and you’ve gone through your severance or emergency fund—you might have to start drawing down your investment or retirement accounts.

The standard advice is to minimize taxes by withdrawing money first from your taxable accounts, especially if your income is now low enough to qualify for tax-free capital gains. Gains on investments held for more than a year will be taxed for most investors at a rate of 0%, 15% or 20%. For 2019, the 0% rate will apply for taxpayers with taxable income up to $39,375 on individual returns and $78,750 on joint returns.

Next, tap your tax-deferred retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s or traditional IRAs. Withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income at rates ranging from 10% to 37%. Try to save Roth IRAs for last so your investments can grow tax-free as long as possible.

Avoid retirement-plan penalties. If you’re forced to retire before age 59½ and need to tap your savings, be mindful of early-withdrawal penalties—and strategies to avoid them. You can withdraw your contributions at any time from a Roth without a penalty. You can avoid taxes and a penalty on the earnings, too, as long as you have owned the Roth for five years and you’re at least 59½.

If you pull money out of a 401(k) or traditional IRA before age 59½, you could be subject to a 10% early-withdrawal penalty. But with a 401(k), if you leave your job in or after the year you turn 55, you won’t pay a penalty for early withdrawals from the 401(k) associated with that job. This option disappears once you roll the 401(k) into a traditional IRA, says Scott Bishop, a CFP in Houston.

Drawing money from a traditional IRA before age 59½ can trigger a 10% penalty and should be a last resort. But some early retirees in need of money may have no other option. You can avoid the penalty by using the so-called 72(t) rule, in which you agree to take out “substantially equal periodic payments” from the IRA for five years or until you turn 59½, whichever is longer. The IRS offers three methods—amortization, annuitization and required minimum distribution—to calculate your payments based on your account balance and life expectancy. Your payments are locked in once you start, although the IRS permits a one-time switch from the amortization or annuitization method to the required minimum distribution calculation if, for example, you want to reduce the size of your withdrawals.

“You have to look at the 72(t) very carefully before you do it,” says Bishop. If you violate the rules, you will owe a retroactive 10% penalty on your withdrawals. To give yourself more flexibility, Bishop recommends splitting a large IRA into at least two accounts (more if the balance is very large). You can start your 72(t) payments from one IRA, and if you later need extra income, you can start 72(t) payments on another, he says.

Review your portfolio. An early retirement can throw your mix of stocks, bonds and cash out of whack. You might have been investing heavily in stocks, figuring you wouldn’t need that money for 10 years or so. But if you must start drawing from your portfolio early, you’ll need to invest the money you’ll be spending in the next year or two more conservatively, so it won’t be at risk if the stock market tumbles, says Rand Spero, a CFP in Lexington, Mass. He suggests parking cash you’ll need in the next few months in a money market account from an FDIC-insured online bank that pays a healthy interest rate and investing money needed in a year or two in short-term CDs and U.S. Treasuries. But don’t get too conservative with your portfolio. You’ll still need the growth that stocks provide to keep up with inflation for decades.

Take Social Security sooner or later? If you have no other sources of income, you may have to apply for Social Security retirement benefits as early as possible, at age 62. (Taking benefits at 62 also makes sense if you are in poor health and don’t expect to live for decades in retirement.) However, your benefits will be reduced by as much as 30% compared with what you would have received if you waited until your full retirement age—which is 66 to 67 for workers now in their fifties and early sixties.

If longevity is in your genes or you’re married, delaying Social Security can provide generous long-term rewards. For every year you delay Social Security beyond your full retirement age, your benefit grows by 8% until age 70. That’s likely a higher return than you’d earn from an investment portfolio, says Mark Fonville, a CFP in Williamsburg, Va. And for couples, having the higher earner delay Social Security until age 70 ensures that the survivor will get the largest possible benefit.

Cover health care. If you lost your insurance along with your job, you’ll need to find coverage until age 65, when you’re eligible for Medicare.

If you’re married, you might be eligible to join your spouse’s workplace plan. Or you can maintain coverage under COBRA, the federal law that allows you to stay on your employer’s plan for up to 18 months after leaving your job. But you must pay your share and the employer’s share of the premiums, which can be steep.

You might find a better deal through your state’s health care exchange (see healthcare.gov for links to state exchanges). You don’t have to wait for open enrollment if you lost your job. Generally, if you don’t have access to a workplace plan (including a spouse’s), you may also qualify for a subsidy that could reduce your premiums by thousands of dollars annually.

To get the subsidy, you must fall within certain income limits—a threshold that you’re more likely to meet if you’re not collecting a paycheck. For 2019, you can receive a subsidy if your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) is up to $48,560 for singles, $65,840 for a couple and $100,400 for a family of four. Go to the Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator at kff.org to see if you qualify for the subsidy and the estimated subsidy amount.

If your household income is slightly over the threshold, you may be able to reduce it so you can qualify for the subsidy. Contributing to a health savings account or boosting contributions to a working spouse’s 401(k) can reduce modified adjusted gross income. The amount you withdraw from tax-deferred accounts matters, too—even a small reduction in withdrawals could make you eligible for the subsidy. Another option, particularly if you don’t qualify for a subsidy, is to shop for a policy through an online broker or buy directly from the insurer.

See if you qualify for disability. If you must retire because of a disability, you may be eligible for Social Security disability insurance, which will provide a monthly check to you. To qualify, you must have a medical condition that will keep you from doing basic work activities for at least a year. In most cases, you must have worked five out of the past 10 years before your disability began and stayed long enough in jobs in which you paid into the Social Security system. You can apply online at SSA.gov.

Your initial application may be denied, but you can appeal. Bishop, the Houston CFP, says the application he filed on behalf of his father, a hospital administrator who suffered a stroke at age 58, was denied, so he hired an elder-law attorney to appeal. That worked, and Bishop now advises others to seek professional help either to handle the initial application or the appeal.

Generally, once you’ve received Social Security disability for two years, you’ll qualify for Medicare, even if you’re younger than age 65.

Downsize. If you need to make bigger cuts to your living expenses, consider moving to a smaller place—or even to a cheaper state.

That’s what Lydia and Chuck Jenkins of New Bern, N.C., did after both of them retired because their jobs had been eliminated. Chuck, 65, lost his job as a network engineer for a telecommunications company in 2016. Lydia, 64, worked in human resources at a biotech company until early this year, when her position was replaced by an automated system. In February, the couple relocated from Thurmont, Md., to North Carolina. They now live in a three-bedroom house that’s about half the size of their Maryland house, but their mortgage is less than one-third of their old payment. Plus, taxes are lower in North Carolina, Chuck says (see Kiplinger's Retiree Tax Map for the most and least tax-friendly states for retirees).

Lump sum or annuity?

If you leave an employer that provides a traditional pension, you’ll likely be asked if you want to take it in a lump sum or as an annuity that will pay you an income for life.

There are advantages and risks to both options, says David Kudla, founder of Mainstay Capital Management in Grand Blanc, Mich. The advantage of rolling a lump sum into an IRA, he says, is that you’ll be able to decide when to withdraw money and control taxes on those withdrawals. You can leave a lump sum to heirs if you’re in poor health and unlikely to collect many pension checks. You may also be able to invest the money to keep up with inflation; most pensions don’t have cost-of-living increases, and your purchasing power decreases over time. Plus, if your employer fails and its pension is taken over by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., which insures private pensions, the PBGC may not cover the full pension you’re due, Kudla says. (The PBGC’s maximum annual benefit for plans it takes over in 2019 is $43,742 for a 60-year-old, or $39,368 with a survivor benefit.)

But traditional pensions are disappearing, and their value shouldn’t be underestimated. For example, suppose you were offered a pension that paid a $1,490 monthly benefit for life for a 60-year-old man, or $1,445 for a woman. To buy an annuity that paid the same amount, you would need $300,000, according to immediateannuities.com.

With the annuity option, you also have the ability to choose survivor benefits, so if you die before your spouse does, he or she will continue to receive a check. And taking a lump sum puts all of the investment risk on you. How confident are you that you will be able to successfully invest that money throughout retirement? A 2017 MetLife study found that 20% of workers electing to take a lump sum depleted the cash in 5½ years. “There is a behavioral benefit” to a monthly pension check, says Mark Fonville, a certified financial planner in Williamsburg, Va. “It can be immensely liberating, knowing every morning that you wake up, you’re going to get your payment.”

If you’re unsure which option is best for you, have a financial professional run the numbers and the scenarios for you.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you may be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in Retirement

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in RetirementMaking Your Money Last Here's why you might regret an RV in retirement. RV-savvy retirees talk about the downsides of spending retirement in a motorhome, travel trailer, fifth wheel, or other recreational vehicle.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Moves

Estate Planning Checklist: 13 Smart Movesretirement Follow this estate planning checklist for you (and your heirs) to hold on to more of your hard-earned money.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.