A Roth Conversion Boosts Medicare Costs

Medicare beneficiaries who convert to a Roth IRA should plan for an unexpected cost: higher Part B premiums.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article was published in the January 2010 issue of Kiplinger's Retirement Report. To subscribe, click here.

Medicare beneficiaries who convert a traditional IRA to a Roth should plan for an unexpected cost: higher Part B premiums. If the conversion pushes your taxable income above a certain threshold, you'll pay an income-adjusted surcharge on Medicare premiums for a year or two.

A lot of attention is being paid to the fact that if you convert to a Roth in 2010, when the $100,000 income limit for conversions disappears, you'll have to pay income tax on the amount you convert. In 2010 only, you can delay reporting the conversion for one year, and then split the converted amount in half on your 2011 and 2012 returns, paying part of the tax in 2012 and part in 2013.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

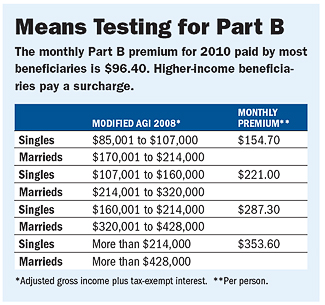

Less well-known is that the new conversion rules are running headlong into means-testing for Medicare beneficiaries. Since 2007, the Part B premium is calculated based on adjusted gross income. The 2010 premiums are based on taxable income in 2008. Income added as a result of a Roth conversion will be cranked into the Medicare Part B calculation.

Here's how it works. Let's say Mr. and Mrs. Green convert $500,000 in 2010. If they pay the entire tax bill in 2010, their Part B premium in 2012 would be at least $353.60 for each spouse each month -- a total of $8,486.40 for the year. That would compare with $2,313.60 the couple would pay if they didn't convert and paid the $96.40 monthly premium. (These calculations are based on the 2010 premiums; the 2012 premiums have not been determined yet.)

The higher premium would only be for one year. If the Greens' income returns to its preconversion level in 2011, the Social Security Administration would readjust the Part B premium downward for 2013.

Let's say Mr. and Mrs. Black took the delay-and-split route on their Roth conversion. They would convert the $500,000 in 2010. They would report $250,000 of income in 2011 and $250,000 in 2012.

In this case, the Blacks would then pay a higher Part B premium in 2013 and 2014. Because their income each year would be between $214,001 and $320,000, they each would pay a monthly premium of $221 -- a total of $5,304 a year.

The prospect of paying higher Part B premiums for a year is not likely to discourage F. Earl Morrison, 66, from converting about $200,000 in 2010. The size of the conversion, plus other taxable income, would require that he and his wife, Arlene, each pay a Part B premium of at least $287.30 a month in 2012.

Morrison has two possible goals for the conversion. The couple could use the converted amount in late retirement, after years of compounded tax-free growth recoups the tax hit in 2010. The Roth could also be left as a tax-free nest egg for their children.

Morrison figures that income-tax rates may rise in 2011, when President Bush's tax cuts are set to expire. If he's right, and he defers the conversion and splits the tax bill over 2011 and 2012, then his tax bill will be higher. "I think I will go ahead and pay taxes in 2010 and take a one-year hit on the Medicare Part B premium," says Morrison, a retired federal government auditor who lives in Clermont, Fla. "When faced with not-perfect information, you have to synthesize it the best you can."

Mark Luscombe, principal analyst for CCH, a provider of tax information, offers another twist, noting that not converting to a Roth could push up premiums for years to come. Why? Because payouts from a traditional IRA -- required once you reach age 70 1/2 -- are taxable income for purposes of the Medicare surcharge. After you take the hit in the year (or years) you report the Roth conversion income, any withdrawals from the Roth are tax-free.

For more authoritative guidance on retirement investing, slashing taxes and getting the best health care, click here for a FREE sample issue of Kiplinger's Retirement Report.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.

-

457 Contribution Limits for 2024

457 Contribution Limits for 2024retirement plans State and local government workers can contribute more to their 457 plans in 2024 than in 2023.

-

Roth 401(k) Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth 401(k) Contribution Limits for 2026retirement plans The Roth 401(k) contribution limit for 2026 has increased, and workers who are 50 and older can save even more.