How to Save for Retirement If You Don't Have a 401(k)

You may have options that are nearly as attractive—but you'll play by a different set of rules.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

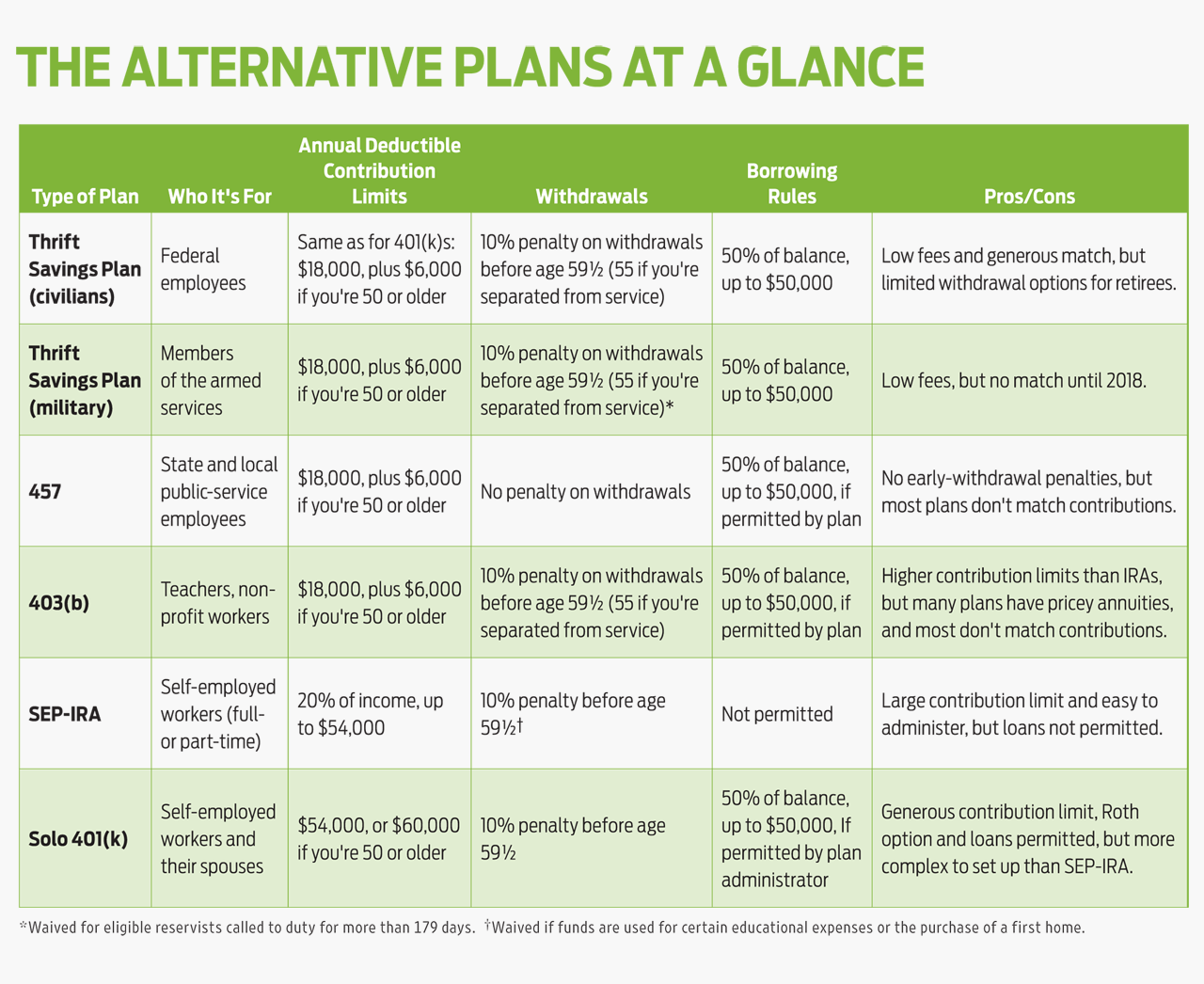

For millions of Americans, a 401(k) plan is an essential item in the employee playbook. As far as benefits go, vacation days are great and nobody objects to free parking, but a 401(k) plan could mean the difference between enjoying a comfortable retirement and never retiring at all. Yet a significant slice of the workforce doesn't have access to this savings tool. Their ranks include teachers, public-service workers, people who work for themselves, and employees of companies that don't offer a retirement savings plan. If you fall into one of those categories, you still have options, but the rules for saving and investing may vary.

Thrift Savings Plan

The Thrift Savings Plan—the federal government's version of a 401(k) plan—has almost 5 million participants. Nearly 90% of civilians who are covered by the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) participate in the TSP. Federal government workers can contribute up to $18,000 to their plans in 2017 ($24,000 if they’re 50 or older). Contributions to a traditional TSP are deducted from their paychecks before taxes and grow tax-deferred.

The TSP was designed to supplement a small government pension and Social Security. The government offers a calculator you can use to figure out how much to save, based on expected payments from your pension and Social Security, at www.tsp.gov/PlanningTools/Calculators.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Federal employees covered by FERS automatically receive a contribution of 1% of their pay, whether or not they contribute any of their own money. But if you stop there, you’ll leave a lot of money on the table. The government matches contributions dollar for dollar on up to 3% of basic pay, and 50 cents on the dollar for the next 2%. You can continue to contribute up to the maximum, but the government matches only 5% of your pay.

The TSP offers the lowest investment fees you’ll find anywhere: 0.029% a year. Its portfolio is made up of five index funds that invest in large companies, small companies, international firms, fixed-income investments and government securities. You can choose your own investment mix or invest in one of the lifecycle funds, which have diversified portfolios of index funds that gradually grow more conservative as you approach retirement.

As is the case with most large 401(k) plans, you can borrow half of your balance, up to $50,000. The TSP offers two types of loans: a general-purpose loan, which must be paid back in five years, and a residential loan, which must be used to buy or build a primary home and has a repayment plan of up to 15 years.

In 2012, the government added a Roth option to the TSP. As is the case with a Roth 401(k), contributions are after-tax but withdrawals are tax- and penalty-free as long as you’ve had the account for at least five years and are at least 59½ or older when you take the money out.

You can roll money from traditional IRAs and other employer-provided retirement plans into your plan, even after you’ve left your government job. Didi Dorsett of Alexandria, Va., who retired from the Navy in 2007, rolled her TSP into an IRA at the suggestion of a financial adviser and now regrets closing the account. Even leaving a small balance in the TSP would have given her the option of rolling other tax-deferred accounts into the plan, says Dorsett, who is training to become a certified financial planner (CFP). “The expense ratios are unbeatable, and they offer an incredibly sound selection of investments.”

Members of the uniformed services don’t currently receive a match, and their participation rate is much lower—about 45% as of August 2016. That’s unfortunate, says Audry Batiste, who became a CFP after retiring from the Air Force. Batiste served for 20 years, which makes him eligible for a pension, but many members of the military don’t stay in the service that long. Contributing to a TSP, he says, “is giving yourself some predictability and additional options” for retirement income. Batiste contributed to his TSP when he was in the service and still has money in the account. He opted against rolling it over to an IRA because he wanted to continue to take advantage of the plan’s low fees.

The main downside to the TSP is that its withdrawal options are not as flexible as those for IRAs and many large 401(k) plans. Participants are allowed only one partial withdrawal, in which they can take out as much as they want. After that, the only option is a full withdrawal using one or a combination of the following: a lump sum for the entire amount, an annuity, or a series of monthly payments that will be paid until the account is depleted. If you opt for monthly payments, you can change the amount of the payments only once a year.

Lynn Alsup, 66, of Lee’s Summit, Mo., uses the monthly payment option to supplement his other retirement income. Alsup, an electrical engineer, started contributing to the TSP as soon as he was hired by the federal government in 1992. Alsup says his regular contributions to the TSP, combined with savings from a former employer’s 401(k) plan, allowed him to retire at age 57. Despite the withdrawal limitations, he says the TSP’s expenses are so low “that it doesn’t make any sense to do anything else with it.” If you want more flexibility to take distributions after you retire, you’ll probably need to roll at least some of your savings into an IRA. The agency’s board has proposed more-liberal withdrawal rules, but any changes will require an act of Congress.

457 Plans

These plans are typically offered to employees of state and local governments. They resemble private-sector 401(k) plans in many respects, but there are some key differences—both good and bad.

As with 401(k) plans, participants in 457 plans have pretax contributions deducted from their paychecks. The contribution limits are the same as they are for 401(k) plans. In 2017, workers can contribute up to $18,000 ($24,000 if they’re 50 or older). More than half of large 457 plans allow participants to borrow from their accounts.

Unlike the majority of large-company 401(k) plans and the civilian side of TSP, however, most 457 plans don’t match employee contributions. Public-sector employees are also more likely to receive a traditional pension than private-sector workers, and those two factors may explain why only about 55% of public-sector employees with access to a 457 plan contribute, compared with more than three-fourths of those who have access to plans that offer a match.

But even if you’re confident you’ll receive a pension when you retire, you might still want to fund a 457 plan because it offers important benefits that could pay for health care and other big expenses in retirement. First, you can withdraw funds from a 457 plan at any time without paying a 10% penalty, although you’ll still have to pay income taxes on withdrawals. (Participants in 401(k) plans must wait until age 55 to take penalty-free withdrawals, assuming they have left their job, and IRA owners must wait until they’re 59½.) To take advantage of this feature, avoid rolling your plan into an IRA when you leave your job.

A 457 plan also offers a way to supercharge your savings during the final years of your public-service career. Instead of making catch-up contributions, workers who are within three years of their “normal retirement age”—typically the age at which they collect their full pensions—can double the $18,000 maximum contribution for three years, as long as they haven’t maxed out on contributions in the past. Three years of $36,000 contributions would allow you to shovel up to $108,000 into your plan.

Although 457 plans aren’t covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), which requires plan sponsors to act in the best interests of participants, most 457 plans follow ERISA guidelines, says Gregory Dyson, senior vice president for the ICMA-RC, which provides financial services to public-sector retirement plans. As with any savings program, it’s important to pay attention to your plan’s investment options, particularly fund expenses and administrative fees. In recent years, plan administrators have moved toward using a single investment provider, which has lowered costs, says Dyson.

For example, in 2009, administrators for the MO Deferred Comp 457 plan for Missouri public employees replaced the plan’s more than 30 funds with a portfolio of target-date funds managed by AllianceBernstein. The plan also offers a self-directed brokerage option, but only about 1.3% of participants use it, says Cindy Rehmeier, manager of the plan. Missouri state employees are automatically enrolled in the plan at a 1% contribution rate and must opt out if they don’t want to participate. That accounts for the plan’s higher-than-average 74% participation rate, Rehmeier says.

403(b) Plans

These plans, typically offered to teachers and employees of nonprofit hospitals and health care organizations, have the same tax benefits and contribution maximums as 401(k) plans. But there the similarities end. As with 457 plans, 403(b) plans offered by schools, local governments and churches aren’t covered by ERISA. Some large nonprofit employers adhere to ERISA standards, but most public school districts are reluctant to get in the business of vetting retirement plans. Rather, they turn the job over to insurance and mutual fund sales representatives, who may promote investments that generate the highest commissions rather than the highest returns.

That leaves participants with a mix of high-cost annuities and other insurance products. On average, variable annuities charge 2.25% annually, compared with 1.4% for mutual funds and 0.18% for no-load index funds. Over 35 years, assuming a $250 monthly contribution and a 6% average annual return, an employee who invested in a variable annuity would end up with a balance of $214,429, compared with $255,712 for the mutual fund and $331,820 for the no-load index fund. An analysis by Aon, a retirement consultant, estimates that 403(b) plan participants lose a total of nearly $10 billion in excessive fees.

Some of the investment products sold to public school employees also have surrender charges that make it prohibitively expensive to switch to a less costly provider, says Dave Grant, a Chicago-based CFP who provides financial advice to teachers (he’s also married to one). Grant says one of his clients had to pay $1,000 in surrender charges to get out of an annuity-filled 403(b) plan that had a balance of just $14,000.

A similar experience early in Steve Schullo’s teaching career turned him into an activist for 403(b) plan reform. In 1994, Schullo exchanged high-cost annuities for no-load mutual funds, paying $6,000 in surrender charges. Despite the early setback, Schullo, 69, now retired from the Los Angeles school system, and his partner, a teacher who died in 2015, managed to save enough in their retirement plans to retire early with no debt.

If you’re offered a 403(b) plan, scrutinize the choices available to you. Some lists provided by public school districts include mutual funds with reasonable fees. In that case, it’s worth taking advantage of the tax-deferred growth and high contribution limits available from a 403(b) plan. Unfortunately, the low-expense funds are often mixed in with a smorgasbord of pricey products, says Schullo. “You almost have to be a private eye,” he says. “There are options, but teachers don’t know about them.”

Some school districts offer both a 403(b) plan and a 457 plan, and you can invest up to the maximum in both. If you have that option and the 457 plan is superior, max it out first. Another alternative for teachers with lackluster 403(b) plans is a Roth IRA. In 2017, you can contribute up to $5,500, or $6,500 if you’re 50 or older, to a Roth. You can withdraw the money tax-free after age 59½, and you can tap contributions without paying taxes or penalties at any time.

On Your Own

About 35% of the U.S. workforce (some 55 million people) work for themselves, according to a survey by the Freelancers Union and Upwork, a website for freelancers. Whether you’re self-employed by preference or necessity, saving for retirement is a challenge. You can’t rely on your employer to deduct contributions from your paycheck or motivate you to contribute by offering a match. Plus, when you’re starting out, you may be inclined to plow all of your income back into the business. But putting aside some funds for retirement isn’t just a smart long-term strategy. It can also reduce the taxes you’ll pay on your hard-earned income.

SEP-IRA. This plan lets you set aside up to 20% of your self-employment income—even if you only have a side gig—up to $54,000 in 2017. All of that money will be sheltered from the tax man (although you’ll be taxed on withdrawals when you take it out). Most brokerage firms, banks and mutual fund companies offer SEPs, and you can usually invest in the same mutual funds, bonds and other investments available to the firm’s IRA investors.

SEP-IRAs are easy to set up and track, but you can’t borrow from your stash. You have until the tax deadline of April 17, 2017, to set up and contribute to a SEP for 2016, or October 16, 2017, if you file for an extension.

Solo 401(k) plan. Designed for self-employed people who have no employees other than their spouse, it allows you to sock away a lot more money for retirement than a SEP-IRA. You can contribute both as an employer and an employee, up to a maximum of $54,000, or $60,000 if you’re 50 or older.

You can borrow from your solo 401(k) if the provider allows it (not all do)—in most cases, up to 50% of the balance. You can also invest some or all of the employee contribution (up to $18,000 plus catch-up contributions of up to $6,000) in a solo Roth 401(k), if your provider offers that option. Contributions to a solo Roth are after-tax, but once you retire, withdrawals are tax-free. And unlike with Roth IRAs, there are no income restrictions on contributions to a Roth 401(k).

In the past, solo 401(k) plans were often burdened with high fees, but that’s no longer the case. Financial firms such as Fidelity Investments and Vanguard Group offer solo 401(k) plans with low (or no) set-up costs and administrative fees.

No Plan From the Boss?

The disappearance of private-sector pensions has left most workers with no choice but to save on their own. Even those starting out have gotten the memo: Start saving as soon as possible and let the magic of compounding pave the way for a comfortable old age. But what if your employer doesn’t offer a retirement plan?

That’s the dilemma facing more than 55 million employees, most of whom work for small businesses, says David John, senior strategic policy adviser for AARP’s Public Policy Institute. “If you work for an employer that has more than 100 employees, the odds are very high you’ll have a workplace retirement plan,” he says. “If you work for a smaller employer, the odds are very high that you won’t.” Cost is a major reason, John says. Small businesses are usually too busy trying to keep their businesses afloat to deal with the complexities of setting up a workplace retirement plan, and some business owners worry about legal liability, he says.

Most of these employees must rely on IRAs to save for retirement. Contributions to a traditional IRA are deductible if your employer doesn’t provide a retirement savings plan or pension. Roth contributions aren’t deductible, but you can withdraw the money tax-free after age 59½, and you can tap contributions at any time without paying taxes or penalties. But IRA contribution limits aren’t nearly as generous as those for employer-sponsored retirement plans. You can invest up to $5,500 in a traditional or Roth IRA in 2017 ($6,500 if you’re 50 or older).

Filling the gap. State lawmakers are trying to close the gap. Eight states have enacted state-sponsored plans for employees who don’t have a retirement plan at work, and more than a dozen others are considering similar plans as a way to encourage workers who aren’t saving to at least establish an IRA. The states are expected to begin launching the plans in 2017.

California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland and Oregon will require small businesses to offer payroll deduction into state-sponsored IRAs. Employees are automatically enrolled and must opt out if they don’t want to participate. Massachusetts has a state-sponsored plan for employees of nonprofit organizations. New Jersey and Washington have programs that provide a marketplace for small businesses that want to offer a retirement plan. Participation by small businesses and enrollment by their employees will be voluntary.

The plans have the same limits as an IRA you establish on your own: Contributions max out at $5,500 in 2017, or $6,500 for workers 50 and older. That’s much lower than the amount employees can contribute to a traditional 401(k). But research shows that very few people contribute to an IRA on their own (most existing IRAs are rollovers from employer-sponsored plans), so it’s a start, John says.

Thrift Savings Plan: More Perks for the Military

Members of the uniformed services who invest in the Thrift Savings Plan don’t currently receive a match for contributions. But starting in 2018, new members of the military will receive the same match that civilian employees receive, says Kim Weaver, a spokesperson for the TSP. Existing members of the military with 12 years or less of service will have the option of receiving matching contributions in exchange for a reduction in their pension.

However, some servicemen and servicewomen get a deal not available to any other federal employee: Income earned when serving in a designated combat zone is excluded from federal tax. If they invest that money in the Roth TSP option, withdrawals won’t be taxed, either—so they’ll never pay taxes on contributions or earnings. “It’s a great deal that a lot of deployed service members don’t know about,” says Russell Robertson, a retired Army colonel and certified financial planner in Springfield, Va.

Battling for a Better 403(b)

Last year, St. Louis attorney Jerome Schlichter filed class-action lawsuits against eight colleges and universities, charging that participants in their 403(b) plans have paid millions of dollars in excessive fees. Many of the plans offer retail share classes of mutual funds, even though less costly institutional share classes are easily available for large retirement plans, Schlichter says. In addition, he says, the plans offer a “dizzying array” of investment options, which drives up costs and hinders investment returns. “When you have a large number of options, it causes decision paralysis,” he says. The suits also charge that the schools imposed improper fees for record-keeping and administrative services.

Scott Dauenhauer, a certified financial planner in Murrieta, Calif., who writes “The Teacher’s Advocate” blog, says the college and university plans singled out by the lawsuits are vastly superior to most 403(b) plans offered to primary and secondary school teachers. If K–12 educators had access to funds offered by TIAA, Vanguard and Fidelity, as is the case with many college professors, he says, “I don’t think there’d be a need for people like me to advocate on behalf of teachers.”

TAKE OUR QUIZ: Are You Saving Enough for Retirement?

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.