Put Your Pension to Work

How you decide to take this endangered asset may be crucial to a secure retirement.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Fretting about how to manage your pension is like complaining about the cost of winterizing your beach house. Lots of people would love to have your problem.

Only about 18% of private-industry workers have a defined-benefit pension. Less than one-fourth of Fortune 500 companies offered a defined-benefit plan to new employees at the end of 2013, down from 60% in 1998, according to Towers Watson, the human resources consulting firm. The number is much larger for public-sector workers; about 80% of them have a traditional pension.

If you're eligible for a traditional pension, you'll be faced with important decisions that could affect your financial security, and they're usually irrevocable. That means when you retire, you'll need to do more than turn in your security badge and wait for the monthly checks to roll in.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Backing away from defined benefits

The move away from traditional pensions reflects several trends. Employees are living longer, which increases the cost of providing a lifetime monthly payment. Low interest rates have reduced pension funds' investment returns, requiring companies to put more money into their plans to avoid a shortfall. Government regulations designed to protect pension participants have increased the cost of offering and maintaining defined-benefit plans. Finally, companies used to view pensions as a way to attract and retain good employees. But these days, a benefit that rewards longevity is a lot less valuable because workers change jobs every 4.6 years, on average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Even if you're among the minority of private-sector workers covered by a pension, you're not immune from efforts to reduce pension costs. AT&T, Boeing and IBM have joined other companies with big pension obligations in switching to a cash-balance plan. These hybrid plans combine features of a 401(k) and a traditional pension. Benefits from a traditional pension are typically based on a participant's salary during the final years of employment, but with a cash-balance plan, benefits are accrued evenly over time. When a company converts, participants are usually entitled to the benefits they've earned to date under the traditional formula, with future benefits based on the cash-balance calculation. For longtime employees, the shift can result in a big cut in benefits.

Other companies have frozen pension benefits. The number of plans with frozen benefits rose from 10% in 2003 to 32% in 2011, according to Russell Research, a financial research firm based in East Rutherford, N.J. Many companies have cushioned a pension freeze by providing higher contributions to workers' 401(k) plans. That could pay off for young workers who haven't accrued much in the way of pension benefits, but a freeze can be costly for mid-career workers. Their future raises and years of service won't be factored into their pension, and they'll have less time to make up the difference by contributing to a 401(k), even if it comes with a generous employer match.

In the past, pension participants could count on the payouts they were promised once they started receiving benefits, but that's changing, too. A new law allows multi-employer pension plans to cut benefits for current and retired workers. These plans typically provide coverage for union members who work for different companies, usually in the construction, manufacturing and trucking industries. Because of a decline in employment in those sectors, the plans have come under severe financial stress. In October, the Central States Pension Fund, a multi-employer plan that covers more than 400,000 participants, proposed cutting its benefits by an average of 22%. Some retirees will see their benefits cut by up to 60%.

A nice problem to have

Carin Hoch, 58, vice president of real estate for NuStar Energy in San Antonio, vividly recalls a meeting she and her husband, Ron, had about five years ago with their financial adviser to discuss financing a retirement home. After reviewing their salaries, retirement savings and other assets, the adviser turned to Ron and said, "She's a keeper." The reason: Hoch will retire with a traditional pension.

Hoch hasn't decided whether she'll take her pension as lifetime payouts or a lump sum when she retires. The Hochs have other sources of retirement income, including 401(k) plans, but having a pension in the mix has given them options they wouldn't otherwise have. It has made it possible for Ron to retire at age 59 so that he can help care for Carin's father, who is 93. It will allow Carin to retire in four to six years. It even helped them get a lower interest rate on the mortgage for their retirement home because it showed "financial stability."

The couple plan to use the income from Carin's pension and Social Security to pay for their living expenses. They'll spend money from their 401(k) plans on travel and other discretionary items. Considering what can happen in the stock market, Carin says, having a pension "really gives us a comfort zone."

Not only that, but retirees like the Hochs can invest money in their retirement accounts and other savings more aggressively, which offers the potential for higher returns. A monthly annuity payment "is like a bond portfolio," says Charles Sachs, a certified financial planner in Miami. "You can buy riskier assets because you have this cushion of dollars coming in."

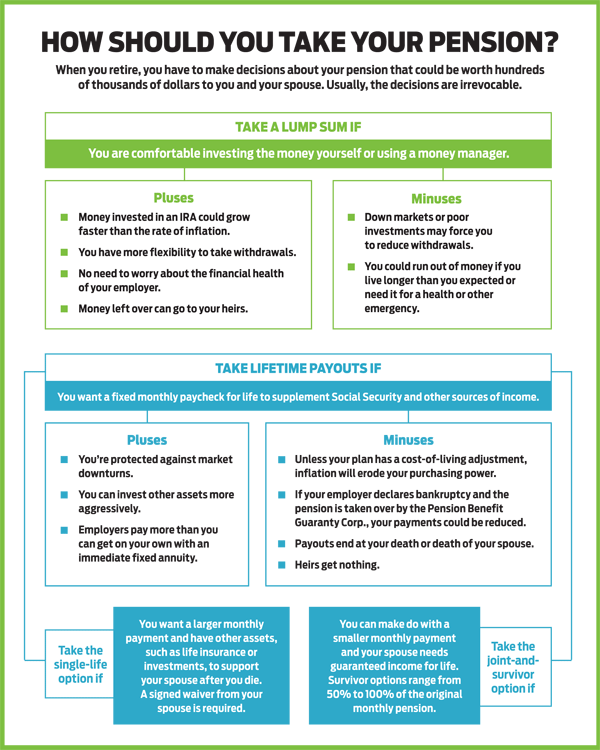

Lump sum versus lifetime payout. If, like Hoch, you're covered by a pension, this decision may be the most important one you'll face when you retire. As employers look for ways to rid themselves of costly pension liabilities, they're increasingly offering to pay departing employees a lump sum in lieu of a lifetime annuity payout. Figuring out which option is right for you will depend on a number of factors, ranging from the size of the lump sum to how long you expect to live.

Look for these offers to increase over the next few months. In 2017, the IRS is expected to update the mortality tables it uses to calculate corporate pension obligations to reflect the fact that retirees are living longer. That change will increase the amount of money companies must put aside to meet their pension obligations. It will also require them to offer larger lump sums to departing employees in exchange for future income that is expected to last longer.

A lump sum could lighten the load for your employer, but it may not be the best choice for you. The lump-sum payment is supposed to equal the present value of the payments you'd receive in the future, based on an estimated rate of return and your estimated life expectancy. But if you expect to live longer than that -- and there's a good chance you will -- the annuity will probably be a better deal. That's particularly true for women, who have a longer life expectancy than men, and couples, who can stretch the annuity over both spouses' lifetimes.

If you take the lump sum, you must shoulder the responsibility -- and risks -- of investing the money yourself. Suppose, for example, that you're 65 and your company gives you a choice of a $300,000 lump sum or $2,000 a month in a single-life annuity. If you take the lump sum and expect to live another 18 years, you'll have to generate a 4.16% return annually to receive $2,000 a month as you draw down the interest and principal. But if you think you'll live another 30 years, you'll need a return of 7.31% a year.

Another way to evaluate the value of a lump sum is to figure out how much it would cost on the open market to buy an annuity that would provide the same lifetime payout you'd get from your pension. Low interest rates have depressed payouts from immediate annuities. Your company payout is likely to be higher because your employer is on the hook for the promised dollar amount, no matter how much it costs to make good on that obligation. A fee-only financial planner, or a Web site such as www.immediateannuities.com, will help you run the numbers.

With the lump sum, you must also figure out how much you can withdraw each year without running out of money. "It's hard to budget for an unknown period of time," says Stephanie Lee, a CFP in San Francisco. "It can be very easy for that money to go quickly."

And it's difficult to put a value on the peace of mind that comes from having a guaranteed paycheck for life. When Paula Lampley's husband died last year, she had to choose between taking his pension from Harley-Davidson as a lump sum or a lifetime payout. Lampley, 55, of Milwaukee, decided in favor of the lifetime payout, which has helped her fulfill a lifelong dream of starting an early childhood development center. The monthly payments, although modest, provide a backstop if her business, Four Seasons Learning Center, doesn't work out.

When the lump sum is better. There are situations in which the lump sum is the better option -- particularly if you have other sources of income in retirement. A lump sum gives you the flexibility to take large withdrawals for unexpected expenses. If you have a life-threatening illness or family history of, say, Alzheimer's, taking a lump sum can provide funds for health care or long-term care. Whereas a lifetime payout ends when you and your spouse die, the money from a lump sum that you don't spend can be left to your heirs.

Taking a lump sum also gives you more control over taxes in retirement, says Kevin Reardon, a CFP in Pewaukee, Wis. When you take a lifetime annuity, your monthly payment will be taxed at your ordinary income tax rate. If you take the lump sum and roll the money into an IRA, you'll still pay ordinary income tax rates, but only when you take withdrawals. That gives you the flexibility to take larger withdrawals when your tax rates are lower -- say, because you have less income from investments -- and smaller withdrawals when they're higher. In addition, you can convert some or all of the money to a Roth IRA. You'll pay taxes on the conversion, but the money will grow tax-free, and you won't have to take required minimum distributions when you turn 70 1/2.

If you change your mind, you can always use your lump sum to buy an immediate or deferred annuity. If interest rates go up, as expected, payouts from private annuities will increase. If you wait until you're older to purchase the annuity, the monthly income will also be higher. That's what Kay Kenealy, 54, of Waukesha, Wis., decided to do. Kenealy worked for the state of Wisconsin when she was in her twenties and is eligible for a modest pension when she turns 55 in February. Her options were to take a payout of $300 a month or a lump sum of about $57,000. She decided in favor of the lump sum. In a few years, she'll combine it with some other retirement funds and buy an annuity.

Some companies, eager to get pension liabilities off their books, pay an insurance company to provide lifetime annuities for their employees. If this happens, the amount of your payout won't change. Your payout won't be insured by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., but you will have coverage from your state guaranty association. You can find more information at www.nolhga.com.

Single life versus joint and survivor. If you decide to take a lifetime payout and you're married, you have another important decision to make: whether to take a single-life payment or the joint-and-survivor option. Taking the single-life payment will deliver bigger benefits, but your pension will end when you die. By law, you'll be required to obtain your spouse's consent before taking this option. With the joint-and-survivor alternative, payments will be smaller, but they'll continue as long as you or your spouse is alive.

Andrew Houte, a CFP in Brookfield, Wis., says he worked with one retiree who took the single-life option because her husband had serious health problems and she expected to outlive him. But the woman died suddenly of a heart attack, resulting in an immediate loss of $3,000 in monthly pension benefits for the surviving spouse. As a result, Houte usually recommends joint coverage, even if the spouse who is eligible for the pension is younger.

The survivor benefit is based on a percentage of the pension participant's benefit. Company plans are required to offer a 50% option, which pays the survivor 50% of the joint benefit. Other survivor-benefit options range from 66% to 100% of the joint benefit. In most cases, the lower benefit kicks in no matter who dies first. Choosing one of the higher percentages for the survivor benefit would set initial pension benefits below the level they'd be with the 50% option.

Some married couples try to increase their overall payout by choosing the single-life option and using the extra money to buy life insurance to protect the surviving spouse. Examine the numbers carefully before you sign up. The death benefit may not be large enough to buy an annuity that would replace the lost pension benefits.

The pension safety net

Employers that have decided they can no longer afford their pension plans can't just shut them down and give employees an extra year-end bonus. By law, an employer that wants to terminate its pension must have enough money to pay all of its vested benefits, either in a lump sum or as a lifetime annuity.

If a company files for bankruptcy protection, though, it can transfer its liabilities to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., the federal agency that insures private pension plans. Your pension won't disappear, but it could be reduced. In 2016, the maximum payout is $60,136, or $5,011.33 a month, for a 65-year-old retiree. (The monthly payment is lower if you retire earlier or elect survivor benefits.) Some higher-paid workers, such as airline pilots, have ended up with lower payouts than they would have received if their plan hadn’t been terminated.

Thanks to a string of bankruptcies in recent years, the PBGC is running a $19.3 billion deficit for single-employer plans; the deficit for multi-employer plans is $42 billion (see the accompanying article). In an effort to close the gap, Congress has proposed raising premiums paid by employers by 22% over the next three years. The proposal would increase premiums from $64 per participant in 2016 to $78 by 2019, after which they would be indexed to inflation.

Critics of the increase say it's excessive because the PBGC's deficit for single-employer plans has been dropping. They also claim that Congress is using the increase as a backdoor measure to reduce the federal deficit, and that it will cause more employers to look for ways to reduce their liabilities, such as offering lump-sum payouts and freezing benefits. That could end up weakening the PBGC because a reduction in pension participants would also lead to a reduction in premiums paid by employers.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach Retirement

3 Reasons to Use a 5-Year CD As You Approach RetirementA five-year CD can help you reach other milestones as you approach retirement.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you may be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.