Retire When You Want

Our five-step plan will get you there.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

And the world keeps on spinning. Despite being mauled by the worst bear market since the Great Depression, most American workers continue to save for the future by investing via 401(k) accounts and similar employer-based retirement plans. And the majority of those workers made no changes to their investments during the financial crisis, according to a recent study by Vanguard. Is it because they were confident about their investments -- or too gripped by fear to make a move?

John Ameriks, head of Vanguard's Investment Counseling and Research group, says the study shows that despite the market's volatility, investors still believe stocks are important to have in their portfolios. But other financial professionals worry that such behavior is a sign that inertia remains the primary force in retirement planning. Without significant changes in the way Americans spend, save and invest their money, many won't be able to afford the retirement they want.

In its annual Retirement Fitness Survey, Wells Fargo found that two-thirds of preretirees age 50 and older expect to need more than twice as much money for retirement as they have already saved, yet only 23% have increased the amount they're putting aside compared with a year ago. Plus, a majority of them confess to having no formal plan for retirement saving or spending. "For people in the last ten to 15 years of their working careers, failure to have a thorough retirement plan in place is like driving blindfolded," says Lynne Ford, head of Wells Fargo Retail Retirement.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

A few years ago, when the stock market was still soaring to dizzying heights, many people became obsessed with "the number" -- their individual nest-egg goal that would assure a comfortable retirement. Now the focus is shifting to a different, more important number: how much retirement income your savings will provide.

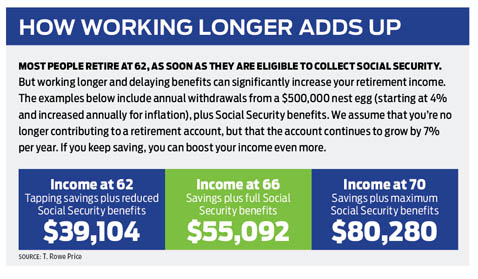

It's a humbling concept when you realize that you need about $1 million to generate just $40,000 a year of income (assuming you stick to a widely accepted rule of thumb that says you should limit your withdrawals to 4% of your savings during your first year in retirement). Throw in the average Social Security benefit of about $20,500 a year for a married couple, and you're up to a little more than $60,000 a year, not counting pensions, part-time work and other sources of retirement income.

After the stock-market debacle, the old joke about how to make a million dollars -- "Start with $2 million" -- hit uncomfortably close to home. Face it, though: Accumulating the magic million was always a stretch. So how do you realize your retirement goals? You take a number of steps, including saving more, reducing your debt, seeking financial advice and possibly working longer.

Perhaps the silver lining of the economic turmoil is the realization that we need to evolve from a nation of accidental investors to stewards of our wealth, committed to saving for both short-term needs and long-term goals. "If you have a plan, take it out, dust it off and check your assumptions," says Ford. "If you don't have a plan, now is the time to make one."

And take some tips from survivors of the meltdown who managed to get their retirement plans back on track.

Cut spending

The aha moment for Kim Thompson came when she sat down for a one-on-one session with a 401(k) counselor that her employer -- Sunny Delight Beverages, in Cincinnati -- provided. Thompson realized how little retirement income she could expect based on her current savings. "When the counselor pulled up my saving profile and showed me what I'd have to live on each month in retirement, I thought, There is no way."

Single and in her forties, Thompson likes to shop, travel and drive a nice car. But after that meeting, she says, "I had to search within myself and ask, Am I willing to sacrifice today for my retirement?" The answer was yes. When the counselor showed her how boosting her 401(k) contributions from 8% to 12% of salary would not make a huge difference in her take-home pay, but could fatten her future retirement income by $20,000 a year, she upped her 401(k) contribution.

But Thompson didn't stop there. She signed up to increase her contributions automatically by 1% a year for the next three years until she reaches the optimum 15%-of-salary contribution rate recommended by many financial experts. And she worked with the counselor to select a more aggressive investment mix to help her achieve her nest-egg goal. "When I came out of that meeting, I felt so good. It was empowering," says Thompson. "Now I feel like I'm on track."

Plus, Thompson is now maximizing the assets in her closet instead of browsing the sales racks. And she has vowed to keep her current car when it's paid off rather than buy a new one. "Being single, I'm on my own," she says. "It's up to me, not anyone else, to get my retirement house in order."

Seek Advice

When it comes to saving for retirement, Eric and Andrea Andrews are of one mind -- and have one investment plan. "Our retirement goals are pretty straightforward: We want to save enough money to enjoy a nice retirement and to have the same standard of living as we have now," says Eric, 38.

Married for 13 years, the Andrewses have both worked for Sprint in Kansas City for nearly a decade. Eric is a corporate lawyer and Andrea, 37, is a staff consultant. Heeding advice from Eric's dad to save early and often, each of them contributes 10% of gross salary to Sprint's 401(k) plan. They'd like to do more, but they are also saving for college for their two young daughters, Molly, 6, and Eliza, 3.

Although the Andrewses have a diversified investment menu through their 401(k) plan, they wanted more guidance than their employer's plan offered. "I felt as if I were stumbling around in the dark," says Eric. So about five years ago, they signed up with Smart401k, a firm that helps employees decide how to choose and manage the investments in their employer-sponsored retirement plans. Smart401k reviewed their savings goals, risk tolerance and investment choices, and made recommendations on how to invest.

Because the Andrewses work for the same company and share the same investment choices and retirement goals, they have one account with Smart401k (for which they pay $200 a year), but each of them follows the investment recommendations. "It's worth the cost," says Eric, particularly during the market meltdown, when the firm urged investors to stay the course. Although the Andrewses lost nearly 40% of their retirement savings in 2008, their balances bounced back to precrash levels by the end of 2009, thanks to the market rebound and their continued contributions. With the extra mutual fund shares they scooped up at bargain prices, and with decades to go before retirement, they are well positioned for future gains.

"One of the benefits of the downturn is that it's a great opportunity to assess where you are and what changes you need to make," says Scott Holsopple, president of Smart401k. Rebalancing your investments periodically to get back to your original asset mix forces you to sell some winners and increase your stakes in underperforming investments -- a great way to follow investing's golden rule of buying low and selling high.

Consider a Roth

The Andrewses are comfortable with their retirement planning. But to hedge their bets against potential future tax hikes, they each split their 401(k) contributions equally between their traditional 401(k) and a Roth 401(k) option. The traditional account reduces their tax bill now, and their Roth contributions will guarantee that a portion of their future retirement income will be tax-free.

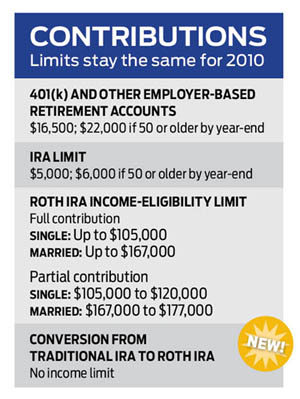

A Roth 401(k) has no income-eligibility limits, but not all employees have access to this type of account. If you don't, you have other ways to secure future tax-free income. Even if you participate in a retirement-savings plan at work, you can contribute to a Roth IRA if you meet the income-eligibility limits. Or, starting this year, you can convert some or all of your traditional IRA money to a Roth, regardless of income.

You'll have to pay income taxes at your regular tax rate on the entire amount, but if you convert to a Roth in 2010, you have a choice: You can pay all the tax on your 2010 return (due in 2011), or you can spread your tax bill over two years, reporting half the conversion on your 2011 return (due in 2012) and the balance on your 2012 return (due in 2013).

Keep in mind, however, that current tax rates expire at the end of 2010, and if Congress raises rates, spreading your payments over two years could mean a higher tax bill. To see how a Roth conversion might affect your tax picture, use Fidelity Investments' free tool at www.fidelity.com/rothevaluator.

Plan your exit

One of the keys to figuring out how much you need to save for retirement is to envision your future lifestyle. Ideally, you should aim to replace about 85% of your preretirement income through a combination of savings, pensions, Social Security and other forms of income, such as a part-time job. If your mortgage is paid off and you don't travel extensively or have expensive hobbies, you might need less. But if you don't have access to retiree health benefits, you might need more.

While many preretirees don't give enough thought to their next stage of life, Jim and Laurie O'Shea talked about nothing else for nearly ten years before they set sail on their retirement voyage -- literally. Jim, a veterinarian, and Laurie, a hospice worker, from Norwich, N.Y., bought a 35-foot sailboat in 2001 and spent the next seven years upgrading the vessel, paying off the loans on the boat and their house, and accelerating their savings to realize their dream of an early retirement at sea.

The O'Sheas encountered some severe headwinds along the way. First, the housing market collapsed, leaving them unable to sell their home. Then the stock market tanked in October 2008, a month after they set out from Lake Ontario for points south. In retrospect, the O'Sheas think that keeping the house turned out to be a blessing. If it had sold, they would have invested the proceeds in the stock market and probably lost a chunk of their money. For now, they have a renter who mows the lawn, shovels the snow and covers the cost of maintaining the house.

With a few minor adjustments, the O'Sheas, both in their late fifties, were able to stay on course. Too young for Social Security and not ready to tap their retirement accounts, they had planned to withdraw about $60,000 a year from their savings. After the market crashed, they still set out to sea but trimmed their sails and their spending -- anchoring at harbors instead of costly marinas and treating themselves to restaurant lunches instead of costlier dinner fare.

On the advice of their financial planner, Bryan Place, head of Place Financial Advisors, in Manlius, N.Y., the O'Sheas had stockpiled three years' worth of living expenses in nonretirement accounts. That gave them plenty of liquidity and allowed their retirement balance to recover from the market's perfect storm.

Place says one of the biggest mistakes that preretirees make is to stash all of their savings in retirement accounts. The tax break is great while you're saving; but when you need money for a major purchase, such as a new car or a down payment on a vacation home, you have to tap your retirement savings and pay taxes at your top tax rate on every penny you withdraw.

Create income

As difficult as it has been for millions of people to save for retirement, transforming those savings into a lifetime of income could be even more challenging. The critical time is when you're within five years of your retirement date, says Philip Lubinski, a financial planner in Denver. Waiting until you retire to readjust your investments may be too late. "That proved to be a disastrous decision for those who were planning to retire in 2009, as they watched their portfolios plummet as much as 20% to 40%," says Lubinski.

In the early years of your retirement, you should draw income from financial products such as certificates of deposit and annuities, which have guarantees and no market risk, he explains. Then you can place the balance of your retirement assets in a diversified portfolio of riskier investments that let you ride out market turbulence. "The result is a strategy that focuses on reliability of income rather than return on investment," Lubinski says. It's a strategy that works best for portfolios of $250,000 or more.

The Mutual Fund Store, a nationwide system of investment-advisory firms founded by radio talk-show host Adam Bold, recently introduced its Retirement Paycheck service. It's designed to provide predictable income, principal protection and the potential for asset growth. It requires a minimum investment of $50,000, and annual fees average 1.5%. A portion of your assets is allocated to CDs and government and corporate bonds to create steady income, and the balance is invested in a diversified portfolio of domestic and international stock mutual funds. Profits from the growth portion of the portfolio are periodically used to replenish the income account, but income is not guaranteed.

Annuities are another way to lock in income. The most basic product is an immediate annuity: You turn over a chunk of cash to an insurance company that promises to send you monthly payments for the rest of your life, no matter how long you live. Because you pool your risk with other annuity holders, you receive larger monthly payouts than you could prudently afford to withdraw from your own savings. The older you are, the bigger your payout.

An immediate annuity can be a good way to stretch your retirement savings, but you may not want to commit to a lifetime income stream at today's low interest rates. One option is to buy an annuity with an annual cost-of-living adjustment. The initial payments are lower than with a fixed-rate annuity, but they rise over time. Another annuity, offered by New York Life, promises that your income will never go down but will rise if a benchmark index increases by at least 2% after five years.

Yet another alternative is a deferred variable annuity, which offers guaranteed income and the opportunity to stay invested in the market. But these insurance products, which allow you to invest in mutual fund-like sub-accounts while guaranteeing you a certain amount of annual income, are complicated and often involve hefty fees of 3% a year. Be sure you ask a lot of questions about the costs and guarantees before you commit to a contract that could tie up your money for years -- and charge stiff penalties if you cancel before the surrender period ends.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.

-

457 Contribution Limits for 2024

457 Contribution Limits for 2024retirement plans State and local government workers can contribute more to their 457 plans in 2024 than in 2023.

-

Roth 401(k) Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth 401(k) Contribution Limits for 2026retirement plans The Roth 401(k) contribution limit for 2026 has increased, and workers who are 50 and older can save even more.