Buckets or Pies: Which Retirement Strategy Works for You?

The standard investing methods have their virtues (and shortcomings), but the key is to apply them thoughtfully and with some flexibility.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

As fee-only financial planners, the overriding concern we hear from people approaching retirement is “will I have enough to live on?” Followed closely by “how can you make my money grow, without exposing it to a lot of risk?” After the dramatic economic downturn in 2008, even the most confident investors can become a bit skittish when they think about relying on their investments for the next 20 or 30 years.

I get concerned when I look at the financial planning industry and the simplistic solutions that it typically offers people.

It seems that a majority of investment firms and advisers default to the traditional methods of statistical backtesting, mean-variance optimization and plotting portfolios along the “efficient frontier” in an attempt to deliver acceptable performance (and if these terms mean nothing to you, don’t worry, they don’t mean a lot to the people who spout their virtues either).

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Now, I’m not saying that there isn’t validity in some of these methods. It is important for competent advisers to understand them, and to also understand their shortcomings.

While any or all of these tools may work well for people in their earning and investing years, they may set up some individuals for an emotional and anxiety-ridden retirement if they are in the hands of an inexperienced adviser.

While the traditional pie-chart approach to investing has its virtues, such as being able to see at a glance how well a portfolio is diversified, it typically is used as data to develop an expected rate of return, and to evaluate how closely it matches an “efficient” portfolio, a la the following image (to give you an idea of how prevalent this theory is, it took me about two seconds to find this on Google):

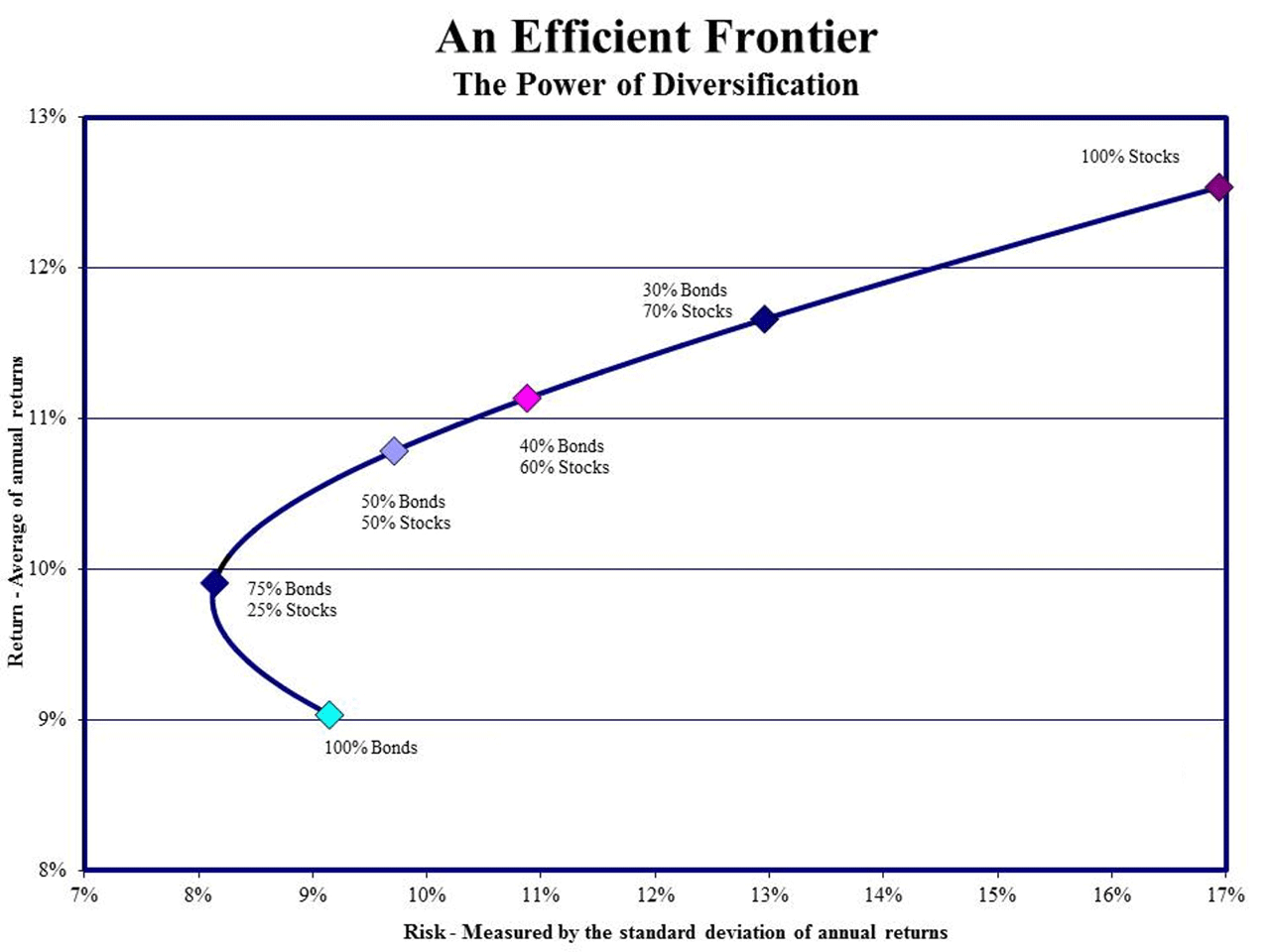

And here's another view:

There are myriad problems with an over-reliance on this approach, not the least of which is that in any given time frame, the assumptions in these charts could get upended. How do you think this last chart would have looked in the 1970s and ’80s when interest rates approached 14%, and the historical risk on bonds was similar (hint: a lot different than this chart, considering bonds’ returns were higher than stocks’, just as they were in the middle of the 2000s). How prudent would it have been to tightfistedly hang on to a set asset-allocation policy back then?

This problematic thinking is not a concern for every investor, as some have adequate sources of outside income (pensions, state or government retirement systems, etc.) or significantly more assets than they could ever use in their lifetimes. But for the person who has just enough of a portfolio to supplement his or her retirement in addition to Social Security, it may be an approach that keeps them up at night.

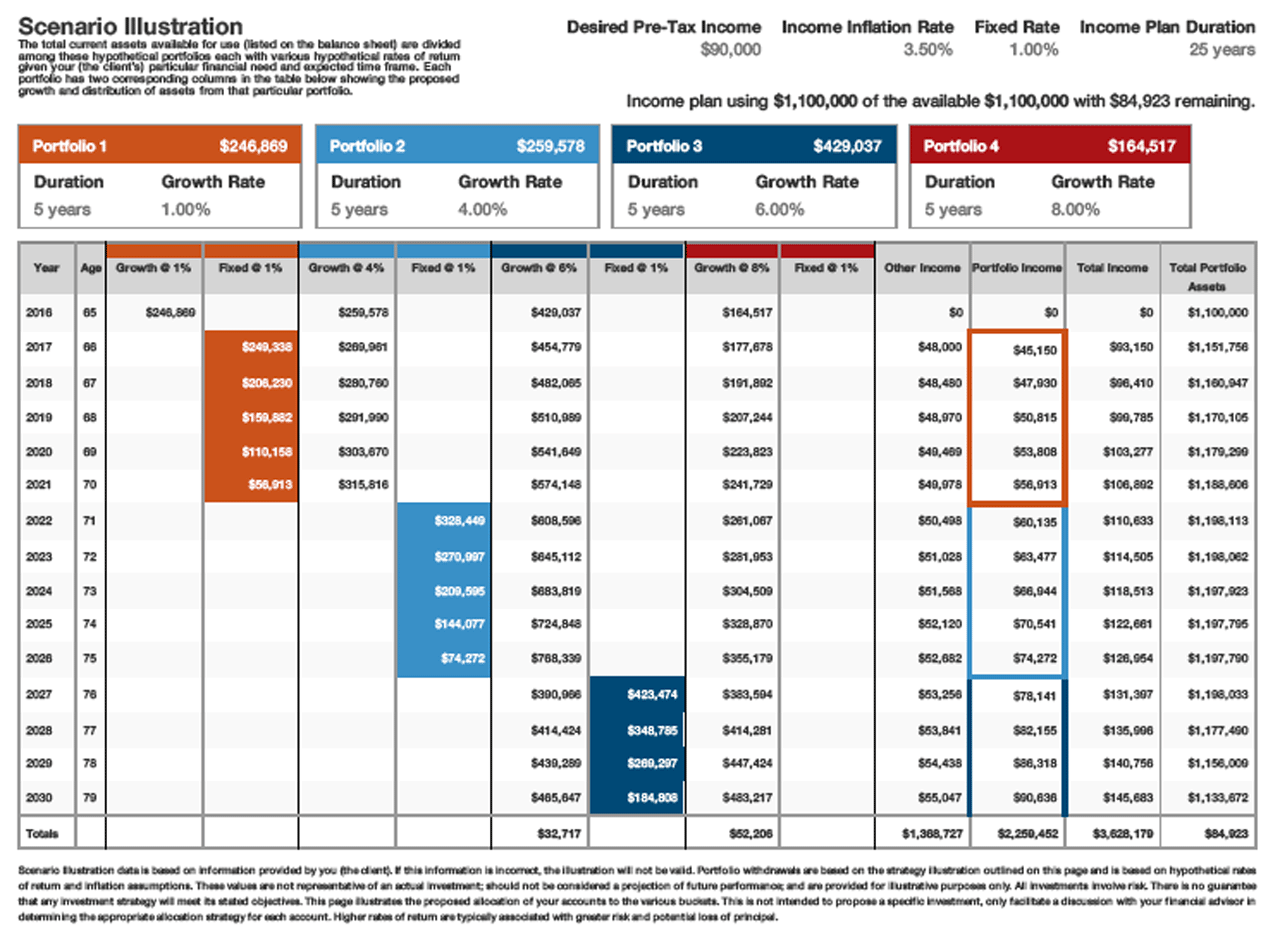

For this client, we recommend the use of a “bucket” strategy. A bucket strategy basically breaks down the projected income needs of the client into segments with varying time frames, depending on his or her expected future goals and needs. Different risk and return assumptions are assigned to each segment relative to the need to be more conservative or aggressive. So a person my have a portfolio with four buckets assigned to it — cash and very conservative investments in the first bucket to get them through the first X years of retirement, followed by a balanced bucket, a moderate bucket and an aggressive bucket.

Now, we can adjust the investment vehicles in these buckets based on economic conditions and forecasts, and also move assets between buckets as needed.

The idea is to commit only the assets that are needed in the near-term to more stable investments, and to reserve more aggressive holdings for later years.

Sample page from a bucket retirement income strategy report:

In addition to being a very practical approach, the bucket strategy tends to make sense to people who don’t spend a lot of time in the financial markets, while also putting their minds at ease. Obviously, you could take this and develop an overall rate of return needed for the portfolio, but there can be a world of difference in concept and understanding. Also, as neat as this looks, it can get a little challenging when applying the strategy across taxable and tax-preferred accounts. One of our goals is to maximize the tax advantages of our retiree client portfolios, so we have to be careful about which assets go where.

In summary, we’ve found that both approaches work, depending on the client’s circumstances, and as long as periodic evaluations and adjustments are made. There are, however, certain indicators that we look for when recommending one strategy over another, as when it comes to retirement income planning, one size does not fit all.

Doug Kinsey is a partner in Artifex Financial Group, a fee-only financial planning and investment management firm based in Dayton, Ohio.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Doug Kinsey is a partner in Artifex Financial Group, a fee-only financial planning and investment management firm in Dayton, Ohio. Doug has over 25 years experience in financial services, and has been a CFP® certificant since 1999. Additionally, he holds the Accredited Investment Fiduciary (AIF®) certification as well as Certified Investment Management Analyst. He received his undergraduate degree from The Ohio State University and his Master's in Management from Harvard University.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're Rich

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're RichSome frugal habits are worth it, no matter what tax bracket you're in.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.

-

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look Like

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look LikeThis is when you should be shifting your focus from growing your portfolio to designing an income and tax strategy that aligns your resources with your purpose.

-

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your Stress

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your StressTo be confident about retirement, consider building a safety net by dividing assets into distinct layers and establishing a regular review process. Here's how.

-

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)The key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)Couples who talk openly about finances, including estate planning, are more likely to head into retirement joyfully. How can you get the conversation going?

-

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares When You Are in the Minority Vote on a Sale of Substantially All Corporate Assets

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares When You Are in the Minority Vote on a Sale of Substantially All Corporate AssetsWhen a sale of substantially all corporate assets is approved by majority vote, shareholders on the losing side of the vote should understand their rights.

-

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan: Don't Leave Your Best Friend to Chance

How to Add a Pet Trust to Your Estate Plan: Don't Leave Your Best Friend to ChanceAdding a pet trust to your estate plan can ensure your pets are properly looked after when you're no longer able to care for them. This is how to go about it.

-

Want to Avoid Leaving Chaos in Your Wake? Don't Leave Behind an Outdated Estate Plan

Want to Avoid Leaving Chaos in Your Wake? Don't Leave Behind an Outdated Estate PlanAn outdated or incomplete estate plan could cause confusion for those handling your affairs at a difficult time. This guide highlights what to update and when.