Retirees, Turn Your Passion Into a Business

More seniors are venturing into the start-up world. Learn how you can launch your own business in retirement.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

For a growing number of seniors, retirement means business—start-up business, to be precise. Starting a business in retirement can be a way to pursue a passion, enjoy an intellectual challenge or simply boost your income. Perhaps you’ve done some consulting as a side gig and want to expand the business. Or maybe you have been downsized and are having trouble finding a new job.

If you are on the brink of retirement and thinking of launching a business, “your age can be a very positive factor,” says Ellen Thrasher, who recently retired as director of the U.S. Small Business Administration’s Office of Entrepreneurship Education. With a wealth of work experience and good-sized nest eggs, many seniors are well positioned to succeed as entrepreneurs.

People age 55 to 64 accounted for 26% of all new entrepreneurs last year, up from 23% in 2013 and 15% in 1996, according to the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. More and more people want or need to continue working into their later years and they’re saying, “I don’t mind working longer, but I want to do it on my terms,” says Michele Markey, vice-president of Kauffman FastTrac, which provides training programs for entrepreneurs.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

But older entrepreneurs also face unique challenges. Because they don’t have decades to recover from a small business going bust, older entrepreneurs must be particularly vigilant about minimizing risks. They should keep a tight rein on start-up costs, avoid heavy debt loads, research the target market and choose a business structure that will protect their retirement savings from a business meltdown. Before diving in, seniors may want to test whether they’re really cut out for the entrepreneurial life—perhaps by volunteering at a business incubator where they can help mentor younger entrepreneurs.

Some seniors stumble into the start-up world by accident—but then become hooked. Elizabeth Isele, 72, was 56 when she launched her first enterprise. She had retired from the publishing industry in New York City and moved to Maine, planning to do some editing and teaching. But when a publisher asked her to help create Web sites, Isele started researching what the Internet was all about—and realized how much seniors could benefit from it. So she launched an organization to provide computer training to seniors. “I was an accidental senior entrepreneur,” she says.

Once bitten by the entrepreneurial bug, Isele became committed to sharing her know-how with other seniors. She has since launched two new ventures focused on helping seniors launch their own businesses: eProvStudio and Senior Entrepreneurship Works. With training, seniors can “understand they’ve been thinking entrepreneurially their entire lives,” even if they’ve never started a business, Isele says.

Get educated

Your first step in exploring entrepreneurial life: Seek out training and mentoring that will help you determine whether you’re cut out to be an entrepreneur, give you feedback on your business ideas and cover some details of launching a business.

The Small Business Administration offers free online courses designed specifically for encore entrepreneurs. AARP offers online tools that help seniors assess whether entrepreneurship is a good fit for their personality and financesstartabusiness. Also check your local community college for courses on writing business plans and other small-business topics.

You can also find more in-depth training designed specifically for encore entrepreneurs. Kauffman FastTrac, for example, offers a 30-hour program for boomer entrepreneurs. The course is available through community colleges and other institutions nationwide.

SCORE, a nonprofit organization supported by the SBA, lets you connect with a small-business mentor by e-mail or participate in online workshops as well as providing in-person training and mentoring. You can also visit Small Business Development Centers or Women’s Business Centers, both overseen by the SBA. Find centers and other resources in your area.

Next, assemble a “kitchen cabinet”—a team of advisers who can give honest feedback and poke holes in your business plan. Include colleagues or acquaintances who have expertise you lack, perhaps in finance or marketing.

Choosing a business

The best businesses for older entrepreneurs are “not capital intensive,” says James Bruyette, managing director at Sullivan, Bruyette, Speros & Blayney, a wealth management firm in McLean, Va. If you launch a consulting business out of your basement, for example, you’ll likely avoid risking savings that you can’t afford to lose.

Consider your appetite for risk. While opening a jewelry store can be a roll of the dice, you may be able to sell items on eBay or Etsy with minimal risk. A franchise can also make sense for some risk-averse entrepreneurs, Markey says, since the business has already been established and there’s marketing help and other support available. Many franchises are home-based and don’t require a storefront.

Consider how much time you want to put into the business, your energy level and your medical condition. Talk to your family about whether they’re comfortable with the amount of time and money you’ll be devoting to the business.

Talk to business owners in the industry you’re considering to be sure you’re realistic about the demands of the business. Some people consider starting a bed-and-breakfast, for example, because they want to spend more time with their family, Markey says. But “the realities of the B&B don’t give you more time with your family,” she says.

When you’ve settled on your idea, write a business plan, which should include your budget, goals, marketing concepts and other details. The SBA offers a step-by-step guide to writing your plan .

[page break]

Safeguard your savings

The legal structure you choose for your business can mean the difference between bankruptcy and financial security if your company goes belly-up or gets slapped with a lawsuit. It can also make a big difference in your tax bill. While a sole proprietorship is the simplest business structure, it puts your personal assets at risk. In a sole proprietorship, there’s no distinction between the owner and the business. You get all the profits but also all losses and other liabilities.

In a limited liability company (LLC), however, owners (known as “members” of the LLC) are insulated from personal liability if the business becomes overloaded with debt or is sued. Profits and losses are passed through to each member of the LLC and reported on their personal tax returns. One potential drawback: LLC members must pay self-employment tax on the entire net income of the business.

The S corporation offers some potential tax savings. As in an LLC, profits and losses can pass through to the owner’s personal tax return. But instead of treating the entire business income as earned income subject to self-employment tax, the S corporation allows you to pay out some business income as a “distribution,” which is taxed at a lower rate. The S corporation is also generally more appealing to small entrepreneurs than a traditional C corporation, which gets hit with double taxation—once at the corporate level and again at the shareholder level.

One approach that can often work well for older entrepreneurs is to form an LLC and elect to be taxed as an S corporation. Legally, your business is an LLC, which means you have less paperwork and administrative hassles than you would as a corporation. But the IRS sees your business as an S corporation, which can mean tax savings. In many cases, this hybrid approach makes the best sense “for ease of set-up, asset protection and tax treatment,” says Steven Potter, a director at Sullivan, Bruyette, Speros & Blayney,

Sites such as LegalZoom can help you generate the documents needed to form an LLC or corporation. Also, many entrepreneurs don’t realize they may need certain licenses and permits issued by their state, county or township, says Eric Kider, vice-president of customer service and operations at CT Corp., which provides incorporation and compliance. Type “licenses” in the search box at SBA.gov to find more information on federal and state licensing requirements.

Minimize start-up costs

Resist the urge to splurge on your brilliant business idea. “We are totally about bootstrapping,” says Sharon Miller, chief executive officer of San Francisco–based Renaissance Entrepreneurship Center, which offers programs for encore entrepreneurs. “Don’t get an office until you absolutely need one. Don’t hire an assistant until you desperately need one. Those are big expenses.”

Launching his third business this summer just as he turns 50, Brian Kearns of Kansas City, Mo., has learned to keep his operations lean. So far, he is the only employee of his new business HipHire, a service that connects employers with part-time workers. His market research was extensive but not expensive. “I got library cards to all the libraries in my city,” Kearns says, where librarians helped him gain access to free databases. He dug up information on other companies in the employment market, including their typical salaries and overhead expenses. He also spoke by phone with more than 3,000 employers and job-seekers, to be sure his service would meet market needs.

To test the market for your product before wading in too deeply, you might donate an item to a silent auction or offer it for sale online. Start with the most basic version of your product or service, and wait for customer feedback before adding costly bells and whistles.

Instead of renting or buying real estate, ask your local small business development centers about shared work spaces. There are “food incubators” that provide industrial kitchens for culinary start-ups, and “maker spaces” full of tools that entrepreneurs can use to manufacture their products.

You can also secure a desk and access to conference rooms and office equipment at shared “co-working” office spaces. In addition to saving money, you get the benefit of networking with other entrepreneurs. Kearns works in a co-working space where he has connected with a public-relations professional, a graphic artist and others who can help his business grow.

To market your business, go to free social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter. Contact your community newspaper, which may be interested in covering the launch of your business. Talk about your business in networking groups, which you can find on sites such as Meetup.com. “Networking is free, and the easiest thing to do,” says Angella Luyk, a SCORE counselor and entrepreneur in Rochester, N.Y.

Financing the start-up

Keep the business small enough that you can finance it with cash that you can afford to lose. Think of a scenario where you lose every penny that you put into the business. “Would it dramatically change your life?” Markey says. “If that’s the case, you may want to rethink it.”

If you’re currently working, consider staying at your job while you launch the business. Small businesses often don’t turn a profit in the first year or so. If you’re still working, “you still have income coming in elsewhere that can help bridge the gap,” Potter says.

It may be tempting to tap your retirement accounts. But “if you need to take your IRA money to fund a business, that’s a good red flag that maybe it’s more than you should take on,” Bruyette says.

Despite the risks, many older entrepreneurs are using their retirement accounts to launch small businesses. Through arrangements known as Rollovers as Business Start-Ups (ROBS), they’re investing their 401(k) money in small businesses without taking taxable distributions. Guidant Financial, a Bellevue, Wash.–based firm that promotes the use of ROBS, says that nearly two-thirds of its customers last year were over 50.

But ROBS are complex arrangements that have been scrutinized by the IRS. First, you must set up a C corporation that sponsors a 401(k) plan. You then roll your existing 401(k) or IRA to the new company’s 401(k), and use the new 401(k) to buy shares of the new company. On top of the administrative complexity, you run the risk of wiping out your retirement savings if your start-up goes bust.

A better route: Establish a close relationship with a banker even if you do not intend to take a loan. You may want to go to the bank or credit union where you hold your personal accounts and open a business account. That way, if your business grows rapidly and you do decide to take a loan, you have a banker who knows your history.

You can also check out crowdfunding options such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo, which can help you solicit donations to get your business off the ground. Backers on these sites aren’t making an investment for financial gains—they’re just making contributions to help projects succeed. Entrepreneurs can thank these supporters by sending them free products or other perks.

The proliferation of such funding alternatives signals exciting times ahead for older entrepreneurs, Thrasher says. “This is a whole new world of entrepreneurship,” she says. “And no one cares what age you are. It’s all about the idea.”

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

The New Reality for Entertainment

The New Reality for EntertainmentThe Kiplinger Letter The entertainment industry is shifting as movie and TV companies face fierce competition, fight for attention and cope with artificial intelligence.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost You

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost YouTaxable Income When Super Bowl LX hype fades, some fans may be surprised to learn that sports betting tax rules have shifted.

-

How to Search For Foreclosures Near You: Best Websites for Listings

How to Search For Foreclosures Near You: Best Websites for ListingsMaking Your Money Last Searching for a foreclosed home? These top-rated foreclosure websites — including free, paid and government options — can help you find listings near you.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Is Relief from Shipping Woes Finally in Sight?

Is Relief from Shipping Woes Finally in Sight?business After years of supply chain snags, freight shipping is finally returning to something more like normal.

-

Economic Pain at a Food Pantry

Economic Pain at a Food Pantrypersonal finance The manager of this Boston-area nonprofit has had to scramble to find affordable food.

-

The Golden Age of Cinema Endures

The Golden Age of Cinema Enduressmall business About as old as talkies, the Music Box Theater has had to find new ways to attract movie lovers.

-

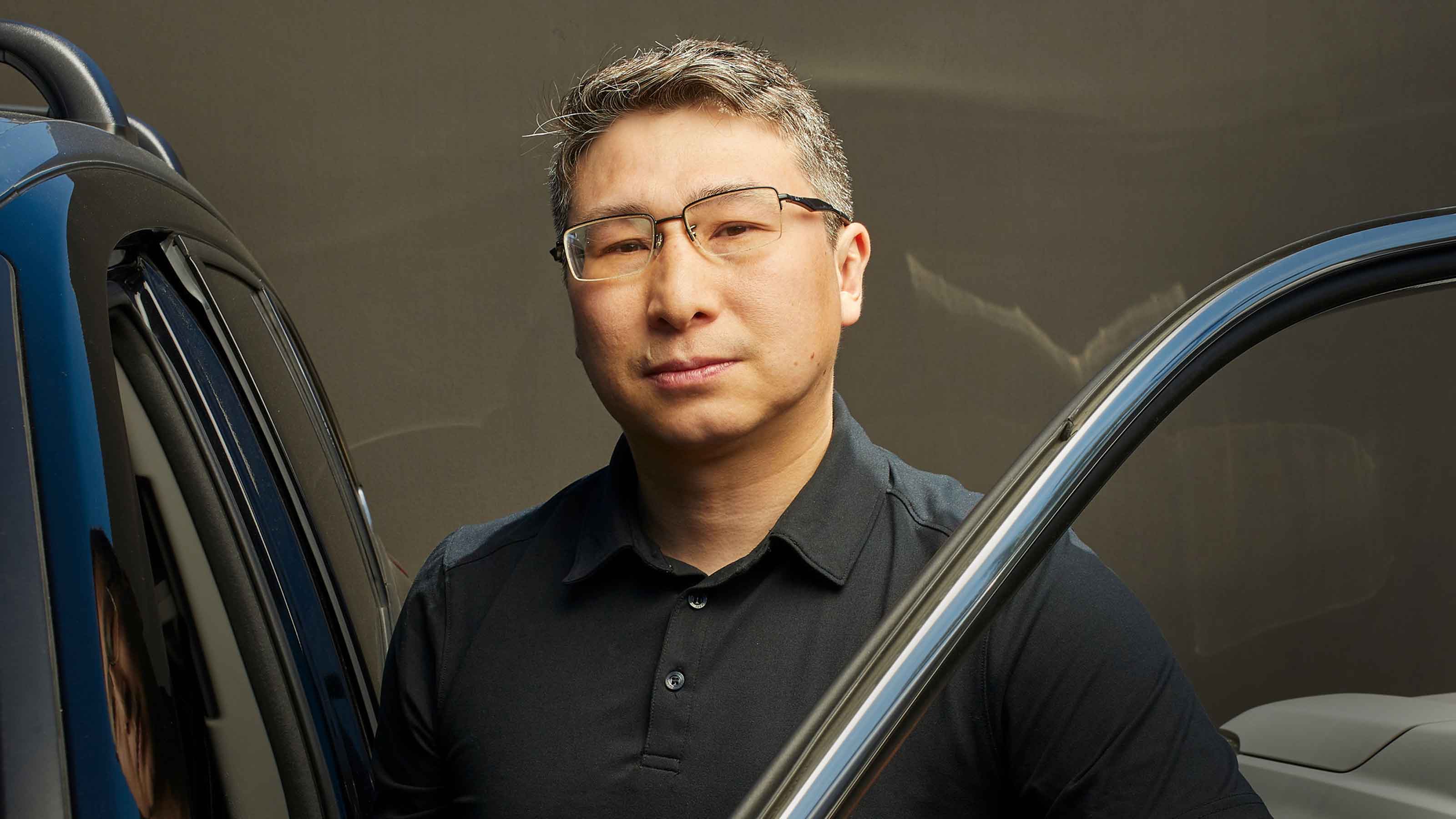

Pricey Gas Derails This Uber Driver

Pricey Gas Derails This Uber Driversmall business With rising gas prices, one Uber driver struggles to maintain his livelihood.

-

Smart Strategies for Couples Who Run a Business Together

Smart Strategies for Couples Who Run a Business TogetherFinancial Planning Starting an enterprise with a spouse requires balancing two partnerships: the marriage and the business. And the stakes are never higher.

-

Fair Deals in a Tough Market

Fair Deals in a Tough Marketsmall business When you live and work in a small town, it’s not all about profit.