Life-Changing Legacy

Rule number one for managing an inheritance: Don't do anything rash.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

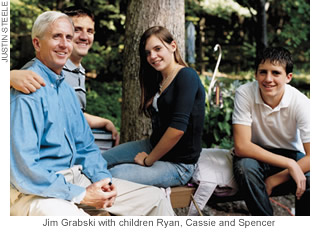

When Jim Grabski's three teenage children come home from school, Jim is there to greet them. He considers that to be his father's real gift, the result of an inheritance that allowed Jim to quit his high-powered job in technology sales. "Financially, the last years I worked were the best I'd ever had," says Jim, 50. "But it wasn't fun anymore."

Now he's able to share parental chauffeuring duties with his wife, Luanne, 49, and work three days a week at a golf course near their home in Reston, Va., largely in return for golfing privileges. He also bowls and pays frequent visits to the gym. "I love my life," he says.

Jim is fortunate. Inheritances are rarely generous enough to finance an early retirement. About 20% of baby-boomer households have received an inheritance, according to AARP, and the median value is $64,000. Handled properly, though, the money can boost your retirement savings, give you financial security, finance a career change or college for the kids, or just let you have a little fun.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Your first move should be to deposit your new wealth in a bank or brokerage account -- possibly one that isn't held jointly with your spouse, advises Martin Shenkman, a tax and estate lawyer in Teaneck, N.J. "Once you commingle inherited money with your spouse's assets, there's a risk that you could lose the protection that inherited assets may otherwise have in a divorce," he says. With the money tucked safely away, there's no need to make hasty decisions about what to do with it. Grabski remained at his job for two years after his father died in 2002, and during that time he and Luanne changed their minds about what to do with their windfall. "At first we thought we'd want to buy a beach house or a bigger home," says Jim. "But as time passed, I became passionate about leaving the workforce."

The Grabskis also paid off their mortgage. But your mortgage may be the one debt you want to keep, if you've locked in a relatively low interest rate and aren't planning to retire right away. Paying off a mortgage at, say, 5.5% is the equivalent of earning 5.5% on your money. On average, you should be able to earn 7% or 8% annually on a good mix of stocks and bonds -- a more profitable use of your funds. Paying off your loan also means losing the tax deduction for mortgage interest.

Taxes

Some inheritances, such as life-insurance proceeds, are tax-free. But, depending on its size, an estate may be subject to federal or state estate taxes. In 2007, estates worth up to $2 million are exempt from federal estate taxes. But more than a dozen states levy their own estate tax, often on smaller estates, and a few states require heirs to pay an inheritance tax.

Record the value of everything you inherit as of the date of your benefactor's death. That date usually determines your new cost basis for tax purposes; you'll be taxed on any appreciation from then until the date you sell the asset.

Inheriting a retirement account, such as a 401(k) or a traditional IRA, is tricky business that requires professional advice. The rules vary depending on whether you're a spouse, a named beneficiary of the account or an heir named in the will.

You can usually inherit a Roth IRA without tax consequences, but that's not true of a regular IRA. If you simply withdraw the money from an IRA or 401(k), you'll owe taxes on the entire amount. Only if the benefactor is a spouse can you roll over an inherited IRA into your own IRA.

The best strategy would be to retitle the inherited IRA as a "beneficiary IRA" in your name and that of the deceased. That way, the money will continue to accrue tax-deferred earnings. In the year following the original owner's death, you will be required to begin taking annual withdrawals based on your life expectancy. Rules approved by Congress in 2006 allow you to convert an inherited 401(k) to a beneficiary IRA and handle it the same way. Previously, only spouses could transfer a 401(k) to their own IRA.

Investing

Don't let sentiment influence the way you handle an inheritance. A portfolio of bonds makes no sense if you're depending on asset growth to finance three decades of retirement, for example. Or perhaps your benefactor hung on to a large stock position to avoid a big tax bill. With the tax slate wiped clean, this could be the time to sell and start fresh.

If you plan to work for another decade or longer, you can afford to take more risk, putting 80% or more of your inheritance into a diversified mix of stocks or stock funds. But if you plan to retire in less than ten years, keep one-third of the money in bonds. And if you're ready to retire and need to tap your investments for living expenses, take a page from the Grabskis and up your bond allocation to 40% with the remainder in stocks.

If your time horizon is shorter -- say, if you're funding college for your teenage children -- you should be more conservative, stashing at least half of your money in high-quality short- or intermediate-term bonds or bond funds. Through a state plan, the Grabskis prepaid tuition for all of their children at any public college in Virginia.

Coming into an inheritance may be the event that prompts you to seek help from a financial adviser. If a one-time session is all you need, financial-planning advice by the hour is available from members of the Garrett Planning Network (866-260-8400; www.garrettplanningnetwork.com) and from many members of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors (800-366-2732; www.napfa.org). Or you may decide to hire a pro to take over the job for you. The Grabskis ended up working with the same Merrill Lynch broker Jim's father had used.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you may be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026

457 Plan Contribution Limits for 2026Retirement plans There are higher 457 plan contribution limits in 2026. That's good news for state and local government employees.

-

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to Know

Medicare Basics: 12 Things You Need to KnowMedicare There's Medicare Part A, Part B, Part D, Medigap plans, Medicare Advantage plans and so on. We sort out the confusion about signing up for Medicare — and much more.

-

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkids

The Seven Worst Assets to Leave Your Kids or Grandkidsinheritance Leaving these assets to your loved ones may be more trouble than it’s worth. Here's how to avoid adding to their grief after you're gone.

-

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SEP IRA Contribution Limits for 2026SEP IRA A good option for small business owners, SEP IRAs allow individual annual contributions of as much as $70,000 in 2025, and up to $72,000 in 2026.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

SIMPLE IRA Contribution Limits for 2026simple IRA For 2026, the SIMPLE IRA contribution limit rises to $17,000, with a $4,000 catch-up for those 50 and over, totaling $21,000.