Stephanie Creary: Making the Case for Diversity on Corporate Boards

Adding underrepresented voices can improve a company’s bottom line.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Stephanie Creary is assistant professor of management at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, where she is an identity and diversity scholar. She has researched workplace diversity practices at a variety of organizations, including corporations, hospitals and the U.S. Army.

Why should investors care whether a company has a diverse board of directors? McKinsey & Co., a management consulting firm, has found that companies with diverse boards outperform their peers. There’s also a lot of academic research that has analyzed the relationship between the composition of top management teams and financial performance. For example, a recent study from the University of Texas at Dallas found that firms that were diverse in upper and lower management performed better than other firms. Their workers were more productive, too. That’s good for the bottom line.

Won’t some companies be tempted to add a token woman or minority to their board? How can that be avoided? First, if you’re a company, you don’t just pick any person of color or woman. You pick people you believe in who will help contribute to the gaps in expertise that you have. And you don’t pigeonhole them into being a single-issue director.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Next, you need to have other players hold corporations accountable. For example, State Street, a major investment management firm, has said that it will vote against board members of companies that fail to disclose the racial and ethnic makeup of their boards. And Nasdaq recently proposed requiring that every company listed on its stock exchange have at least one woman on its board and one board member who is an underrepresented minority or LBGTQ. The firms that don’t meet the standard will be required to explain why they can’t. That’s holding companies accountable.

In 2019, the Business Roundtable, which is made up of the chief executives of the largest U.S. companies, issued a statement encouraging members to take into account the interests of employees, customers and their communities when making business decisions. Have major corporations embraced this philosophy, particularly when it comes to minorities? Yes they have, but one size doesn’t fit all. Target is a good example. After the protests in Minneapolis over the death of George Floyd, the company decided to reopen a store that was damaged by the riots. Target’s approach was to have conversations with people in the community, not just community leaders, about how the store could address their needs. JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup announced last fall that they are changing their lending practices to make sure that people of color have access to mortgages. JPMorgan Chase also said it’s going to tackle the lack of diversity in its own workforce.

When can investors expect to see the results of these initiatives? Investors tend to measure company progress quarterly, but that’s very short-term. A better benchmark is one year from an announcement that a company has changed the composition of its board or has made a commitment to any other social justice movement.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Rivan joined Kiplinger on Leap Day 2016 as a reporter for Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine. A Michigan native, she graduated from the University of Michigan in 2014 and from there freelanced as a local copy editor and proofreader, and served as a research assistant to a local Detroit journalist. Her work has been featured in the Ann Arbor Observer and Sage Business Researcher. She is currently assistant editor, personal finance at The Washington Post.

-

4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs

4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family NeedsThe key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)Couples who talk openly about finances, including estate planning, are more likely to head into retirement joyfully. How can you get the conversation going?

-

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares in This Situation

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares in This SituationWhen a sale of substantially all corporate assets is approved by majority vote, shareholders on the losing side of the vote should understand their rights.

-

How to Search For Foreclosures Near You: Best Websites for Listings

How to Search For Foreclosures Near You: Best Websites for ListingsMaking Your Money Last Searching for a foreclosed home? These top-rated foreclosure websites — including free, paid and government options — can help you find listings near you.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Is Relief from Shipping Woes Finally in Sight?

Is Relief from Shipping Woes Finally in Sight?business After years of supply chain snags, freight shipping is finally returning to something more like normal.

-

Economic Pain at a Food Pantry

Economic Pain at a Food Pantrypersonal finance The manager of this Boston-area nonprofit has had to scramble to find affordable food.

-

The Golden Age of Cinema Endures

The Golden Age of Cinema Enduressmall business About as old as talkies, the Music Box Theater has had to find new ways to attract movie lovers.

-

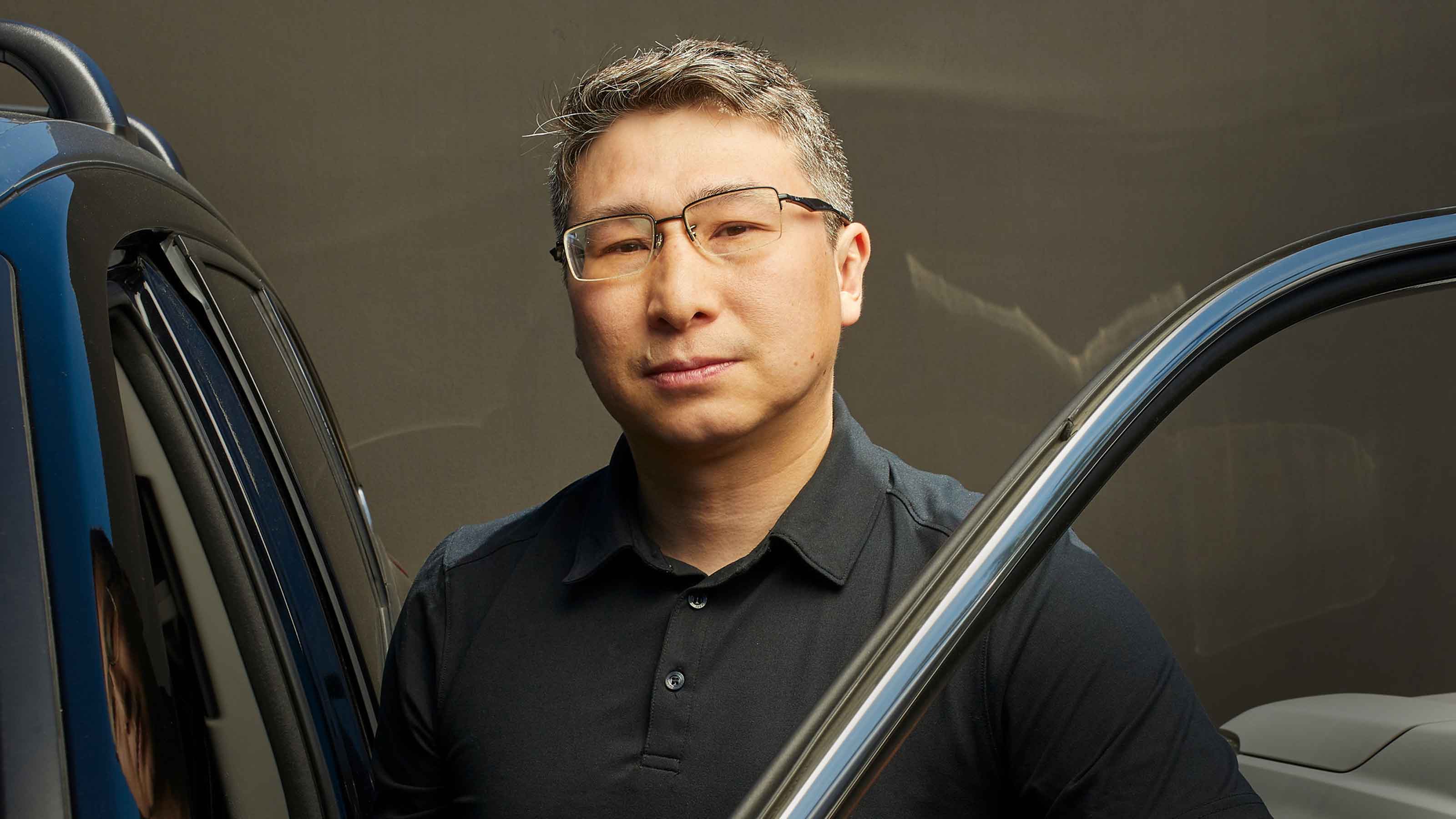

Pricey Gas Derails This Uber Driver

Pricey Gas Derails This Uber Driversmall business With rising gas prices, one Uber driver struggles to maintain his livelihood.

-

Smart Strategies for Couples Who Run a Business Together

Smart Strategies for Couples Who Run a Business TogetherFinancial Planning Starting an enterprise with a spouse requires balancing two partnerships: the marriage and the business. And the stakes are never higher.

-

Fair Deals in a Tough Market

Fair Deals in a Tough Marketsmall business When you live and work in a small town, it’s not all about profit.