Why You Should Consider Commodities

Besides offering protection against inflation, commodities are good diversifiers in a portfolio.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Inflation is still low, but it’s rising. You can see it reflected in interest rates. The yield on 10-year Treasury notes soared from 0.52% in early August to 1.6% in early March. Investors demand higher rates when they worry that rising prices will mean the dollar will have less purchasing power when their bonds mature.

You can also see inflation in the prices of commodities, or basic raw materials. The cost of food rose 3.6% over the 12 months that ended February 28, reports the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the gasoline index jumped 6.4% in January alone. About two dozen commodities—from corn to crude oil to cattle to copper—actively trade on U.S. markets. For some, price increases have been dramatic. Soybeans rose nearly 50% over the past six months; lumber nearly doubled in four months. In a three-week period in February, the price of copper jumped over 20%. (Unless noted, prices and other data are as of March 5; recommendations are in bold.)

Besides offering protection against inflation, commodities are good diversifiers in a portfolio because they are only about 30% correlated with stocks. When one asset is down, the other is often up, and vice versa. But when the stock market tanked last February and March because of the COVID-19 pandemic, so did most commodities—and for the same reason: plunging demand from consumers who lost their jobs. Of course, everyone has to eat, so food prices held up. But other commodities plummeted, before returning slowly but consistently as the economy began to recover.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

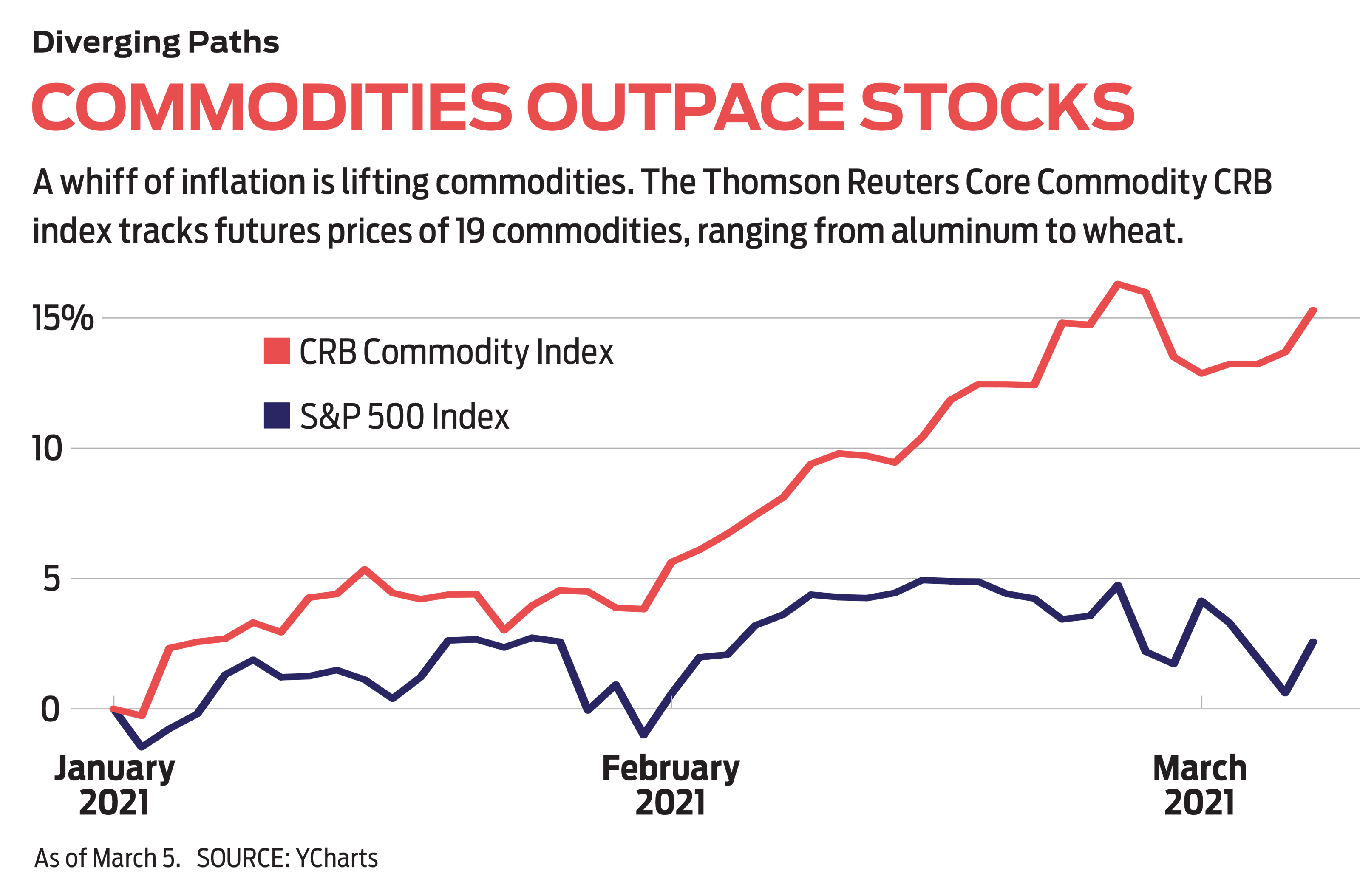

A fork in the road. Stocks and commodities started to diverge significantly as 2021 began. That’s because businesses are allergic to rising interest rates, which increase their own and their customers’ borrowing costs, but the prices of staples are largely unaffected (unless rates get way out of hand and trigger an economic slowdown).

Despite recent price increases, however, commodities have been in a long-term bear market since the 2008–09 recession. A $10,000 investment 10 years ago in a popular exchange-traded security, iShares S&P GSCI Commodity-Indexed Trust (symbol GSG, $15), is now worth $3,878, according to Morningstar. By contrast, the same investment in SPY, the SPDR S&P 500 exchange-traded fund, would have grown to $35,657.

The problem for commodity prices has been sluggish economic growth in the U.S. and Europe, and a decline in the spectacular annual growth in China’s gross domestic product, down from double-digit percentages in the early 2000s to less than 7% today. Global inflation has dropped in major economies to below 2%, despite all the money that central banks keep injecting.

Is the decline in commodity prices long-lasting and the recent upward blip just temporary? Or, as analysts at Goldman Sachs recently predicted, is this “the beginning of a much longer-term structural bull market”? My definitive answer is that I do not know. Inflation is rising and the U.S. economy is getting a huge dose of stimulus. But a powerful low-growth/low-inflation trend is difficult to buck.

I do believe, however, that because accurate predictions about inflation are nearly impossible, all investors should have some exposure to commodities. That doesn’t mean buying them directly in the futures market, where you use enormous leverage to purchase, say, a contract for 5,000 bushels of wheat (recently valued at about $33,000) or 50,000 pounds of cotton (about $45,000).

In these transactions, an investor typically puts up only 3% to 12% of the price of a contract and borrows the rest. Unless you want your backyard filled with hogs or barley, you sell before the delivery date. Right now, you can control a wheat contract for about $1,700. If wheat prices rise by about 5%, as they did in the first two months of the year, you double your money. If prices fall by the same amount, as they did during the month of November, you’re wiped out.

Wise investing has nothing in common with that kind of high-stakes gambling. I had personal experience in commodities when I was in my twenties. It was exhilarating when my first contracts were wins, but then I lost my shirt. So stay away. Instead, try one of the following approaches.

How to invest. First, you can own exchange-traded securities that track broad portfolios of commodity contracts. The S&P portfolio cited earlier is not a standard ETF, but a trust that buys and sells indexed futures contracts, backed by collateral such as Treasury securities. It’s a good choice if you want a heavy energy weighting; crude oil represents 45% of assets.

I prefer the more balanced iPath Bloomberg Commodity Index Total Return ETN (DJP, $25), linked to an index whose target weights are: 30% energy, 23% grains, 19% precious metals, 16% industrial metals and the rest livestock and “softs” such as cotton and coffee. With an ETN, or exchange-traded note, you are actually lending money—in this case, to Barclays Bank—with no guarantee of repayment. The value of the note rises or falls according to the value of the underlying commodities.

Trusts and notes are slightly more risky than standard ETFs, but in these two cases the issuers are sound. The Bloomberg security’s 10-year annualized return is about two points better than the S&P fund’s, but both are negative. For index funds, both have steep expense ratios: 0.76% for the S&P fund and 0.70% for the Bloomberg fund.

The second strategy is to buy individual stocks. A good example is Archer Daniels Midland (ADM, $58), a large supplier and refiner of grains and vegetable oils, that carries a 2.6% dividend yield. Bunge (BG, $78), a smaller, 202-year-old St. Louis company in the same sector, also yields 2.6%. ADM has returned 54% in the past year, and Bunge, 65%, but both should be good values if inflation keeps increasing.

Investing in London-based Rio Tinto Group (RIO, $84), a mining and processing company with a $132 billion market value, is a way to play both precious and base metals—gold, silver, aluminum, molybdenum, copper, iron ore, uranium and more. The stock is yielding 5.6%. An even larger global minerals firm, BHP Group (BHP, $76) of Australia, has been on a tear but trades well below its 2011 high and yields 4.1%. BHP focuses on many of the same commodities as Rio Tinto, with the addition of coal and petroleum.

A smaller, U.S.-based firm that also combines metals with oil and gas is Freeport McMoRan (FCX, $35). Sales have fallen since 2018, but the stock has skyrocketed with rising commodity prices. Still, it’s below its record highs of a decade ago. Freeport pays no dividend. One of my favorite energy stocks is Oneok (OKE, $50), a natural gas processor and pipeline company whose stock is not as volatile as those of production and exploration firms. It yields 7.5%.

Or consider index ETFs, such as SPDR S&P Metals and Mining (XME, $38) and Materials Select Sector SPDR (XLB, $75). The latter has returned an annual average of 9.1% over the past 10 years, mainly on the strength of recent gains. Its top two holdings are excellent stocks on their own, both giant purveyors of industrial gases: London-based Linde (LIN, $248), yielding 1.7%, and Kiplinger Dividend 15 member Air Products and Chemicals (APD, $264), yielding 2.3%. Unlike other commodity stocks, Linde and Air Products have languished since last summer, making them all the more attractive.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market TodayPalantir Technologies proves at least one publicly traded company can spend a lot of money on AI and make a lot of money on AI.

-

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market Today

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market TodayIncoming economic data, including the January jobs report, has been delayed again by another federal government shutdown.

-

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market Today

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market TodayA "long-overdue correction" temporarily halted a massive rally in gold and silver, while the Dow took a hit from negative reactions to blue-chip earnings.

-

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market TodayMicrosoft, Meta Platforms and a mid-cap energy stock have a lot to say about the state of the AI revolution today.

-

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will probably have to wait until after Jerome Powell steps down for the next Fed rate cut.