There's No Vaccine Against Inflation

Prices should ease in 2022, but inflation will remain above the levels of recent years.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

One of the sad ironies of the waning COVID-19 pandemic is that just as Americans feel ready to dine in restaurants, board an airplane or go shopping in an actual store, everything seems a lot more expensive than it was a year ago.

That’s not an illusion. Consumer prices rose 0.9% in October, up 6.2% from a year earlier, the largest increase in 31 years. Prices have risen across the board, affecting everything from eggs to TVs (see the chart below for some of the hardest-hit categories).

Kiplinger forecasts an inflation rate of 2.8% by the end of 2022, a decline from 2021 but higher than the average annual rate of 2% over the past decade. Contributing factors:

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Wage growth. In what has been dubbed the Great Resignation, millions of workers have left their jobs, which has put pressure on employers to pay more to retain and attract employees.

In the third quarter of 2021, wages increased 1.5%, which came on top of a 0.9% increase in the previous quarter and marked the biggest jump in two decades. For the 12 months ending in September, wages and salaries increased 4.2%. It’s unclear, however, whether we’re in what’s known as a wage-price spiral, which occurs when demand for higher wages leads to higher costs and fuels more demand for higher pay.

Product shortages. The pandemic and resulting economic lockdowns created backlogs in delivery channels around the world. Ports are struggling with bottlenecks, warehouses are understaffed, and there aren’t enough truck drivers to move stuff around. That means the goods that are available cost more, particularly at a time when an increase in consumer spending has driven up demand.

The personal savings rate, which measures how much money Americans have left each month after spending and taxes, was 7.5% in September, down from 14.3% a year earlier.

Energy prices. Gas prices rose 3.8% between September and October and are up nearly 50% from a year earlier. Prices at the pump have been driven higher by the strong global recovery in oil demand, coupled with a slow rebound in oil production (see Energy Stocks Come Roaring Back). Kiplinger expects a small dip in gas prices by year-end, but that will still leave motorists paying more than $3 per gallon, on average—and in some parts of the country, gas prices will continue to cost $4 a gallon (or more).

Outlook for interest rates. If inflation persists at more than 2%—which appears likely—the Federal Reserve has signaled that it will raise short-term interest rates in an effort to slow the economy. Kiplinger predicts that the Fed will start raising rates in the fall of 2022, which is earlier than the central bank had anticipated. But that may not offer much relief for people who have money in low-interest savings accounts, says Ken Tumin, founder of DepositAccounts.com.

Banks continue to hold a record amount of deposits, while demand for loans remains weak. That means banks don’t feel the need to raise interest rates to attract more customer deposits, Tumin says. Currently, online savings accounts are paying about 0.5%, with major brick-and-mortar banks paying even less than that.

There is some encouraging news for individuals in search of a low-risk place to stash money they can’t afford to lose: The Treasury announced in November that newly issued series I savings bonds will pay a composite rate of 7.12%. The composite rate consists of a fixed rate, which is currently 0% on new bonds, and an inflation rate, which is tied to the government’s consumer price index and adjusts every six months from the bond’s issue date.

I bonds have some downsides. You’re limited to investing $10,000 a year in electronic I bonds, plus up to $5,000 in paper bonds you can only purchase with your federal tax refund. In addition, you can’t redeem an I bond within the first year. And if you cash it in before five years have passed, the penalty is three months’ worth of interest, although that’s considerably less severe than the early-withdrawal penalties on most five-year CDs.

Because of these withdrawal limitations, I bonds aren’t a good place to invest money you may need right away, Tumin says. However, they could provide a valuable supplement to your emergency savings. For more information on I bonds, go to www.treasurydirect.gov.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

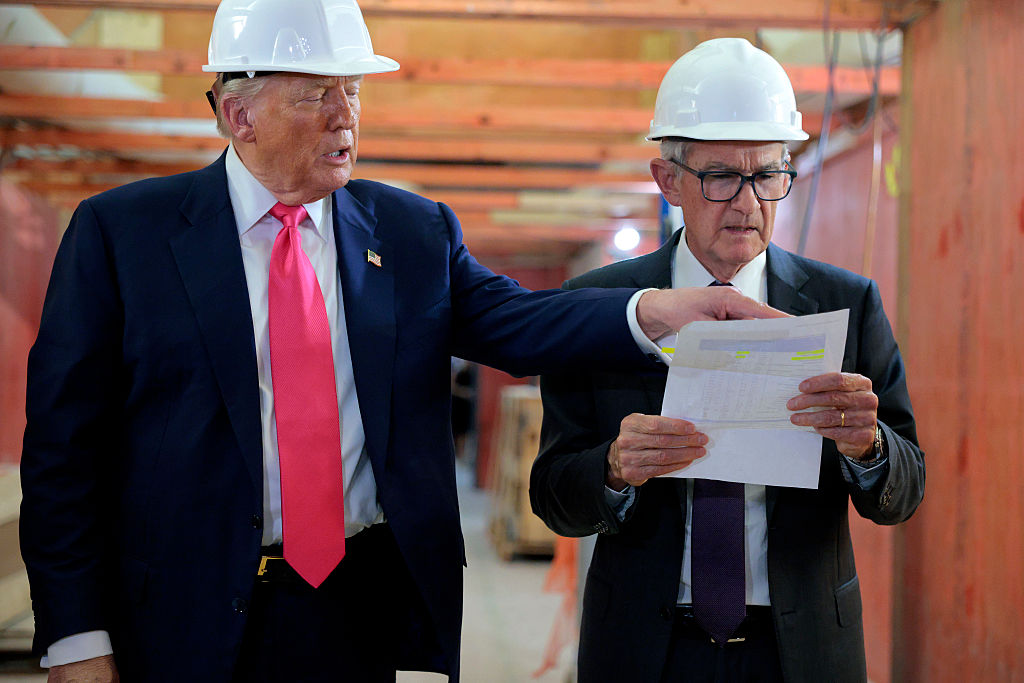

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

The U.S. Economy Will Gain Steam This Year

The U.S. Economy Will Gain Steam This YearThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the projected pace of the economy for 2026. Bigger tax refunds and resilient consumers will keep the economy humming in 2026.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

Trump Reshapes Foreign Policy

Trump Reshapes Foreign PolicyThe Kiplinger Letter The President starts the new year by putting allies and adversaries on notice.

-

Congress Set for Busy Winter

Congress Set for Busy WinterThe Kiplinger Letter The Letter editors review the bills Congress will decide on this year. The government funding bill is paramount, but other issues vie for lawmakers’ attention.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.