How Do Tariffs Impact the Stock Market?

Trump's tariff announcement sent shockwaves through the stock market, and there are still a lot of moving parts. Here, we look at what impact tariffs have on the stock market and your portfolio.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

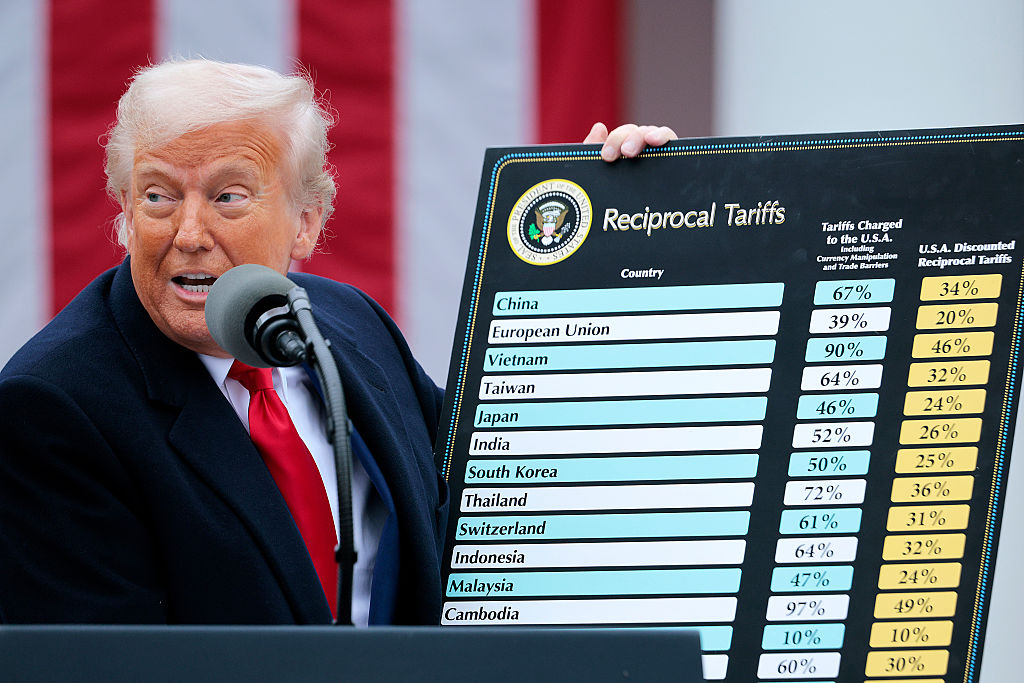

Tariffs: They're the centerpiece of President Donald Trump's second-term agenda, they're controversial, and they raise the price of imported goods.

But until recently, their effect on the stock market was primarily a topic for old economics textbooks. They haven’t been all that impactful since the Great Depression era.

That changed in 2025. Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs on April 2, 2025, led to an immediate two-day, 11% drop in the S&P 500. Why? What was it about the tariffs that led to the sell-off?

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The answer is complex, because there are a lot of moving parts. Let's make it as simple as possible.

How do tariffs work?

First, let's look at the basics. A tariff is a tax on imported goods. Contrary to popular belief, the tax is paid by the importer, not the exporter.

Taking Trump’s recently announced 46% tariff on Vietnamese goods as an example, the Vietnamese government doesn’t pay that; neither do local manufacturers. The American companies that import the merchandise get stuck paying the tax bill.

For example, shares of Nike (NKE) tumbled following the tariff announcement because Nike manufactures about half its shoes in Vietnam. Every shoe Nike imports will get 46% more expensive. Nike has the unpleasant choice of either passing the price hike on to consumers or eating the costs, taking a major hit to profits.

Tariffs will affect companies differently. Retail operations such as Home Depot (HD), Walmart (WMT) and Amazon.com (AMZN) and even mom-and-pop shops will be negatively affected. Logistics and shipping companies could also take a hit, because demand for imports falls when tariffs are high.

On the flip side, domestic producers such as steel and lumber mills primarily benefit from reduced competition. The same would be true for an automaker such as Tesla (TSLA) that manufactures substantially all its vehicles in the United States.

However, these benefits are partly offset by increases in component costs. For example, Tesla might enjoy a pricing advantage over automakers that produce a large chunk of their cars overseas, but they also must pay more for imported aluminum and steel.

Are tariffs normally good or bad for the stock market?

From a macro view, the economic impact of tariffs tends to be negative. But the specific tie to the stock market is harder to measure except in extreme circumstances, such as the "Liberation Day" tariffs. Most tariffs don’t normally result in an immediate 11% repricing of the stock market.

What is normal, and why is this time different?

Free trade allows for specialization and creates a more efficient economy with lower prices and greater consumer choice. This has been a core belief of virtually all economists since Adam Smith first wrote The Wealth of Nations. Tariffs disrupt free trade in goods and can lead to higher prices and fewer consumer choices.

Conceptually, it's easy to grasp that we're all a little poorer if we have to pay an extra $10 for a toaster. But how does that flow through to gross domestic product (GDP) or to the aggregate profits of the S&P 500? Some companies gain, others lose, but the net results aren’t generally going to move the market as a whole.

Another factor: The United States is primarily a services and information economy with world-leading tech, financial and health care firms. This means they stand to absorb the costs of tariffs but see no benefits to compensate, as tariffs are levied on goods, not services.

Tariffs will potentially increase a service company's expenses, meaning they'll pay more for imported electronics and equipment, but won't get any pricing advantage over foreign rivals.

Under normal conditions, tariffs might be a mild negative for the market but not enough on their own to move the needle much.

Why did the market react so much to Trump's tariff announcement?

Why was this time different?

It comes down to size. The "Liberation Day" tariffs were massive, significantly larger than the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariffs that plunged the world deeper into the Great Depression. As I write this, the tariff on Chinese goods is a shocking 104%. The very real likelihood is that we'll have a spike in inflation and a recession at the same time — something we haven’t seen since the 1970s.

Did the market overreact?

That depends on how serious Trump is about keeping tariffs at current levels. If 104% tariffs are the new normal, it’s possible the stock market didn’t react negatively enough.

Trying to price a market such as this is virtually impossible, because there are too many moving parts.

What should investors do about tariffs?

What is an investor to do? Buy the dip? Sell everything and hide?

Perhaps the best bet is to stick to your investment plan. If you own good stocks at good prices, you probably shouldn’t rush to dump them.

Instead, use this time to evaluate your position sizes and the overall level of risk you’re taking. If you’re nervous, there’s nothing wrong with rebalancing to a slightly more conservative portfolio or trimming some of your appreciated positions a little.

Related content

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Charles Lewis Sizemore, CFA is the Chief Investment Officer of Sizemore Capital Management LLC, a registered investment advisor based in Dallas, Texas, where he specializes in dividend-focused portfolios and in building alternative allocations with minimal correlation to the stock market.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

Don't Bury Your Kids in Taxes: How to Position Your Investments to Help Create More Wealth for Them

Don't Bury Your Kids in Taxes: How to Position Your Investments to Help Create More Wealth for ThemTo minimize your heirs' tax burden, focus on aligning your investment account types and assets with your estate plan, and pay attention to the impact of RMDs.

-

Are You 'Too Old' to Benefit From an Annuity?

Are You 'Too Old' to Benefit From an Annuity?Probably not, even if you're in your 70s or 80s, but it depends on your circumstances and the kind of annuity you're considering.

-

In Your 50s and Seeing Retirement in the Distance? What You Do Now Can Make a Significant Impact

In Your 50s and Seeing Retirement in the Distance? What You Do Now Can Make a Significant ImpactThis is the perfect time to assess whether your retirement planning is on track and determine what steps you need to take if it's not.

-

Your Retirement Isn't Set in Stone, But It Can Be a Work of Art

Your Retirement Isn't Set in Stone, But It Can Be a Work of ArtSetting and forgetting your retirement plan will make it hard to cope with life's challenges. Instead, consider redrawing and refining your plan as you go.

-

The Bear Market Protocol: 3 Strategies to Consider in a Down Market

The Bear Market Protocol: 3 Strategies to Consider in a Down MarketThe Bear Market Protocol: 3 Strategies for a Down Market From buying the dip to strategic Roth conversions, there are several ways to use a bear market to your advantage — once you get over the fear factor.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

The Best Precious Metals ETFs to Buy in 2026

The Best Precious Metals ETFs to Buy in 2026Precious metals ETFs provide a hedge against monetary debasement and exposure to industrial-related tailwinds from emerging markets.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.