The Truth About Index Funds

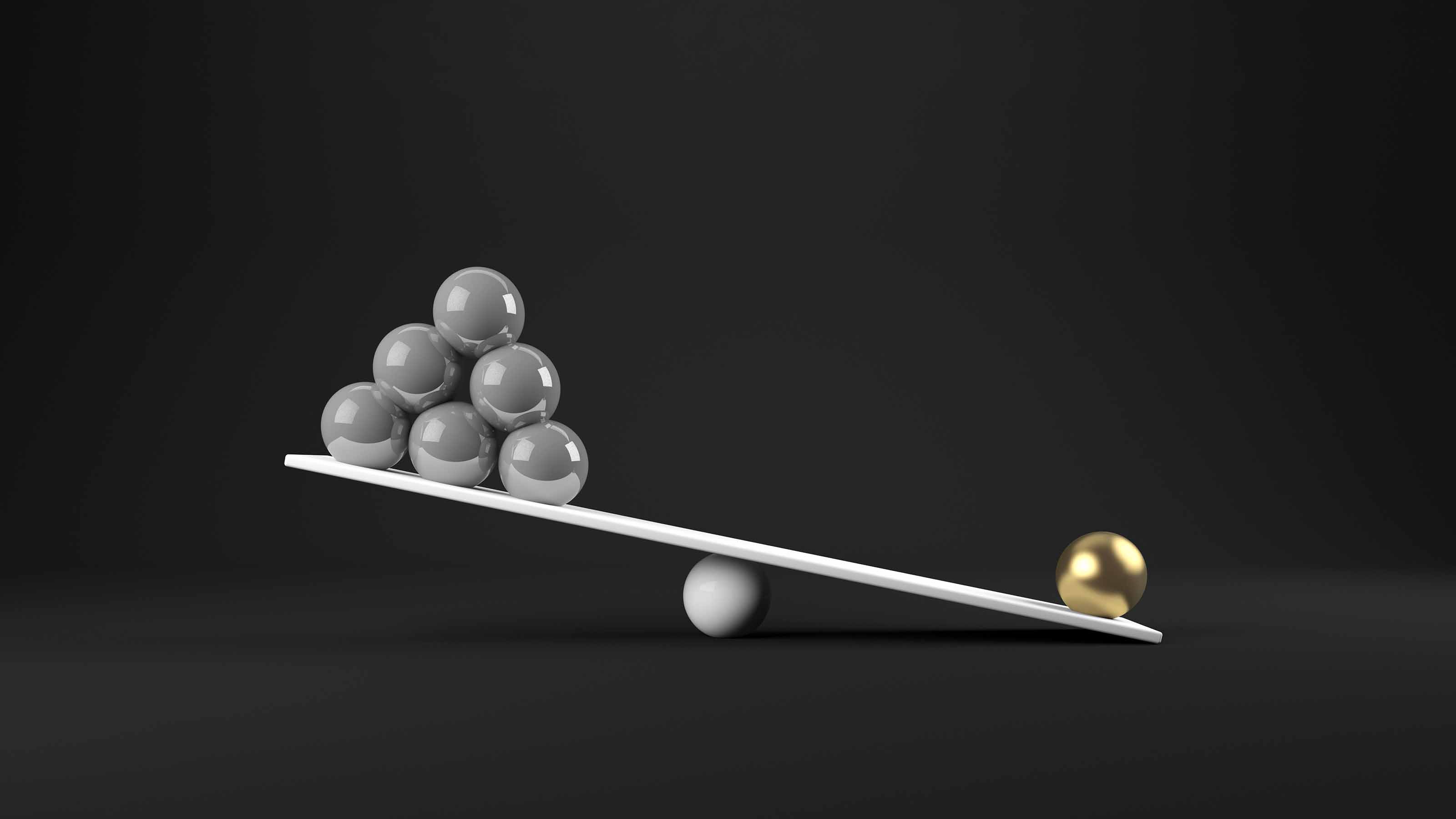

You may think you're diversified by buying an S&P 500 Index fund, but you're making a substantial wager on a handful of stocks.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Index funds, which are designed to mimic the ups and downs of a specific index, from the S&P 500 Index to the Barclays Capital California Municipal Bond Index, have become a runaway success. Index investing was introduced to the public with mutual funds in the 1970s. The strategy got a big boost in the 1990s with the rise of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which can be bought and sold like shares of stock.

It wasn't until the turn of the millennium, however, that index funds really caught on. Between 2010 and 2020, they grew from 19% of the total fund market to 40%, and two years ago, the total assets invested in U.S. stock index funds surpassed the assets of funds actively managed by human beings. The 13 largest stock funds all track indexes.

No wonder: Compared with managed funds, index funds offer better average returns, in large part because their expenses are lower. According to fund-tracker Morningstar, the 10-year return of Vanguard S&P 500 (VOO), an ETF linked to the most popular benchmark and carrying an expense ratio of just 0.03%, exceeded the return of 87% of its 809 peers in the large-cap blend category. The index has beaten a majority of those peers in every single one of the past 10 calendar years.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Also, because only a few of their constituent stocks change each year (the annual turnover rate for the Vanguard fund is just 4%), index funds incur minimal capital gains tax liabilities. (Returns and other data are as of Aug. 6; index funds I recommend are in bold.)

Specialized index funds – ETFs such as the iShares MSCI Brazil (EWZ) or the TIAA-CREF Small-Cap Blend Index (TRHBX) – are straightforward. They let you own a country, region, investing style or industry without having to choose individual stocks or bonds. But what if you want to own the market as a whole, or a big chunk of it? The choices can be overwhelming – and not necessarily what they seem.

Begin with the S&P 500, consisting of roughly the 500 largest U.S. companies by market capitalization (number of shares outstanding times price). Like most indexes, the S&P 500 is weighted by capitalization: The bigger the market cap a company has, the more its influence on the performance of the index. Apple (AAPL), for instance, has about 60 times the impact of General Mills (GIS).

Any cap-weighted index fund is a heavy bet on larger companies. Lately, that bet has become extremely heavy because a few stocks have become gigantic. In 2011, for example, the total market cap of the 10 biggest S&P 500 stocks was $2.4 trillion. Currently, it’s $13.7 trillion. Apple itself has a cap as large today as all 10 of the largest S&P stocks combined a decade ago.

Or consider simply the five trillionaire stocks I highlighted recently. All by themselves, Alphabet (GOOGL), Amazon.com (AMZN), Apple, Facebook (FB) and Microsoft (MSFT) represent 22% of the value of the S&P 500. In recent years, those stocks have been on a tear, and the index has benefited.

Targeted Bet

You may think you are getting broad diversification by buying an S&P 500 Index fund, but you are actually making a substantial wager on a handful of stocks in the same sector. As of July 31, information technology, Apple's category, and communications services, the sector of Facebook and Alphabet, Google's parent, represent a whopping 39% of the S&P 500. By contrast, energy represents just 2.6%.

Most of the other popular broad indexes are similarly top-heavy and focused on technology. Consider the MSCI U.S. Broad Market Index and other gauges that measure all, or nearly all, of the approximately 4,000 stocks listed on U.S. exchanges.

The five trillionaire stocks represent about 18% of the asset value of Vanguard Total Stock Market (VTI), the most popular of the ETFs based on such indexes; that's only a few percentage points less than the trillionaires' weight in the S&P 500. The iShares Russell 1000 (IWB) is an ETF whose portfolio is based on an index of the 1,000 largest stocks. It has about 20% of its assets in the trillionaires; 36% in tech and communications.

I still like the trillionaires, and I like technology, but I have decided no longer to deceive myself by thinking that most index funds tracking the S&P 500 are the best way to own the U.S. market.

Most advisers – me included – urge a balanced approach. For example, I have a personal program of putting the same amount of money every month into each of the dozen or so diversified stocks I own. Then, I rebalance at the end of each year by buying and selling so that each stock is valued roughly the same. Such a strategy makes sense for investing in the broad market as well, but most of the popular index funds don't provide it.

Also, although technology is hot now, sector weightings shift back and forth over time. Don't you want your portfolio tilted toward sectors and stocks that are out of favor?

Between 2014 and 2020, technology ranked in the top four of 11 sectors in all but one year, and it ranked number one in three years. By contrast, energy has ranked last in five of the past seven years, and consumer staples stocks such as Procter & Gamble (PG) have finished in the bottom half of the sector rankings for five years in a row. When you buy the S&P 500, you get a lot of tech but little energy and consumer staples – which is the opposite of what bargain-hunting investors want.

The Equal-Weight Solution

There are, however, ways to avoid loading up on a few stocks, or any one sector.

One is the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index. Each stock represents roughly 0.2% of total assets (there are actually 505 stocks in the S&P 500 Index), with rebalancing at the end of each quarter. As a result, every time the index is rebalanced, the trillionaires account for about 1% of assets; technology and communications, 20%. Over the past 10 years, the S&P 500 has beaten its equally weighted cousin by about one percentage point, annualized, but that's hardly unexpected in a great decade for big growth stocks.

Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight (RSP), an ETF with an expense ratio of 0.2%, offers an easy way to buy the index. Be warned that its turnover, at 24%, is much higher than a standard broad market index fund's turnover, so it's best to own it in a tax-deferred account such as an IRA.

A second index alternative is my old favorite, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, composed of just 30 large-cap stocks. The Dow is price weighted. In other words, the higher the price of a share of a stock, the more the company's influence on the value of the index.

As weird as price weighting sounds, it enhances the diversification of the portfolio because stocks whose price runs up quickly tend to split, and new companies take their place leading the index. (Many large tech companies, especially, rarely split their shares. But as a result, the Dow won't let them in.)

You can buy the Dow through the SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF (DIA), nicknamed Diamonds, with an expense ratio of 0.16%. The fund's 10-year annual average return is nearly two points below the S&P 500's, but that’s not bad considering that tech and communications represent just 22% of the portfolio.

I'm not telling you to avoid conventional broad-market funds. Notice that I am still recommending them. I'm just saying there are other ways to get better diversification and come close to really owning the U.S. stock market.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost You

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost YouTaxable Income When Super Bowl LX hype fades, some fans may be surprised to learn that sports betting tax rules have shifted.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Slides 1.4% on Big Tech Questions: Stock Market TodayPalantir Technologies proves at least one publicly traded company can spend a lot of money on AI and make a lot of money on AI.

-

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market Today

Fed Vibes Lift Stocks, Dow Up 515 Points: Stock Market TodayIncoming economic data, including the January jobs report, has been delayed again by another federal government shutdown.

-

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market Today

Stocks Close Down as Gold, Silver Spiral: Stock Market TodayA "long-overdue correction" temporarily halted a massive rally in gold and silver, while the Dow took a hit from negative reactions to blue-chip earnings.

-

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market Today

Nasdaq Drops 172 Points on MSFT AI Spend: Stock Market TodayMicrosoft, Meta Platforms and a mid-cap energy stock have a lot to say about the state of the AI revolution today.

-

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Tops 7,000, Fed Pauses Rate Cuts: Stock Market TodayInvestors, traders and speculators will probably have to wait until after Jerome Powell steps down for the next Fed rate cut.

-

S&P 500 Hits New High Before Big Tech Earnings, Fed: Stock Market Today

S&P 500 Hits New High Before Big Tech Earnings, Fed: Stock Market TodayThe tech-heavy Nasdaq also shone in Tuesday's session, while UnitedHealth dragged on the blue-chip Dow Jones Industrial Average.