Investing in Uncertain Times

Trust your gut. Buy companies that you believe have terrific ideas even if you are not sure how they will work out.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

At last, 2020—a year of horrifying events and wild markets—is coming to an end. Mainly because of COVID-19, the worst epidemic to hit the United States in 101 years, gross domestic product in the second quarter fell by an incredible 31.4%, and unemployment soared 10 percentage points in April, to 14.7%. That’s the highest rate since official records began.

In the stock market, the Dow Jones industrial average, which reached a record of 29,551 on February 12, fell nearly 11,000 points in just 40 days. By September, however, the Dow had regained nearly all its losses, and both the Nasdaq Composite and the S&P 500 hit new highs, creating the fastest rebound from a bear market in history. The lesson of 2020 is that we live in an era characterized by uncertainty, and investors need to adjust.

I use the word uncertainty in a particular way. Frank H. Knight is a name most people don’t know. But in his time (he received his PhD in 1916 and taught for 50 years), he was an enormously influential economist, the mentor of three Nobel Prize winners. Knight grew up in poverty, one of 11 children, on a farm in Illinois. Perhaps because of the vagaries of an agricultural life, he devised a theory that held, “Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically different from risk.”

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Although risk is something that can be quantified (such as in the case of the 50-50 odds on the results of a coin flip), Knight’s uncertainty refers to a bolt from the blue—something utterly unpredictable. John Maynard Keynes, an economist who borrowed from Knight, wrote: “About these matters, there is no scientific basis to form any calculable probability whatever. We simply do not know!”

To determine the risk in stocks, we can look to history. We know, for example, that the average annual return, including dividends, of the S&P 500 since 1926 is about 10%. If stocks returned 10% every year, there would be no risk at all. Instead, stocks are volatile. The S&P returned between 5% and 15% in just 21 out of the past 92 years—and in 29 of those 92 years, the market fell.

A comforting history. Periods of ups and downs seem entirely random, but there are clear parameters that should give investors some comfort. Since 1939, the market has never fallen more than three years in a row, and it has never suffered a calendar-year decline of more than 38%. And if you hold a portfolio of stocks for at least 20 years without selling it, the chances of your losing money are nil.

Past patterns may not predict the future, but at least markets give us something to go on. Uncertainty, in the Knightian sense, is very different. It is an unmeasurable risk, something that has never happened before—for example, the sudden decline of the stock market on Black Monday, 1987, when the Dow lost 23% in a day; the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001; the financial meltdown of 2008; or the coronavirus pandemic. The Spanish Flu of 1918–19 may have been more virulent, but COVID occurred in an era of advanced medicine and public health, a time when a new disease killing 200,000 people in the U.S. in six months was unthinkable.

My view is that the rapidity of these events is not just bad luck. Rather, the world has grown more uncertain. One reason is that we are more connected. A disease in Wuhan can travel to New York in a few hours. A computer virus launched in Moscow can shut down the electric grid on the East Coast of the U.S. in seconds.

Also, the power of individuals to do great damage has increased exponentially. A person with a gun can kill one or two or maybe 100 people. A few terrorists commandeering planes can kill thousands—with nuclear weapons, millions.

So how should we deal with uncertainty as investors? Not by running from it. Markets, by their very nature, reward investors for taking risks. In fact, Knight’s contribution to economics was to show that entrepreneurs reaped profits because they were willing to challenge a world of uncertainty. Uncertainty, I believe, is a major reason that stock returns are so high today. We’re getting paid extra because the world is extra-uncertain.

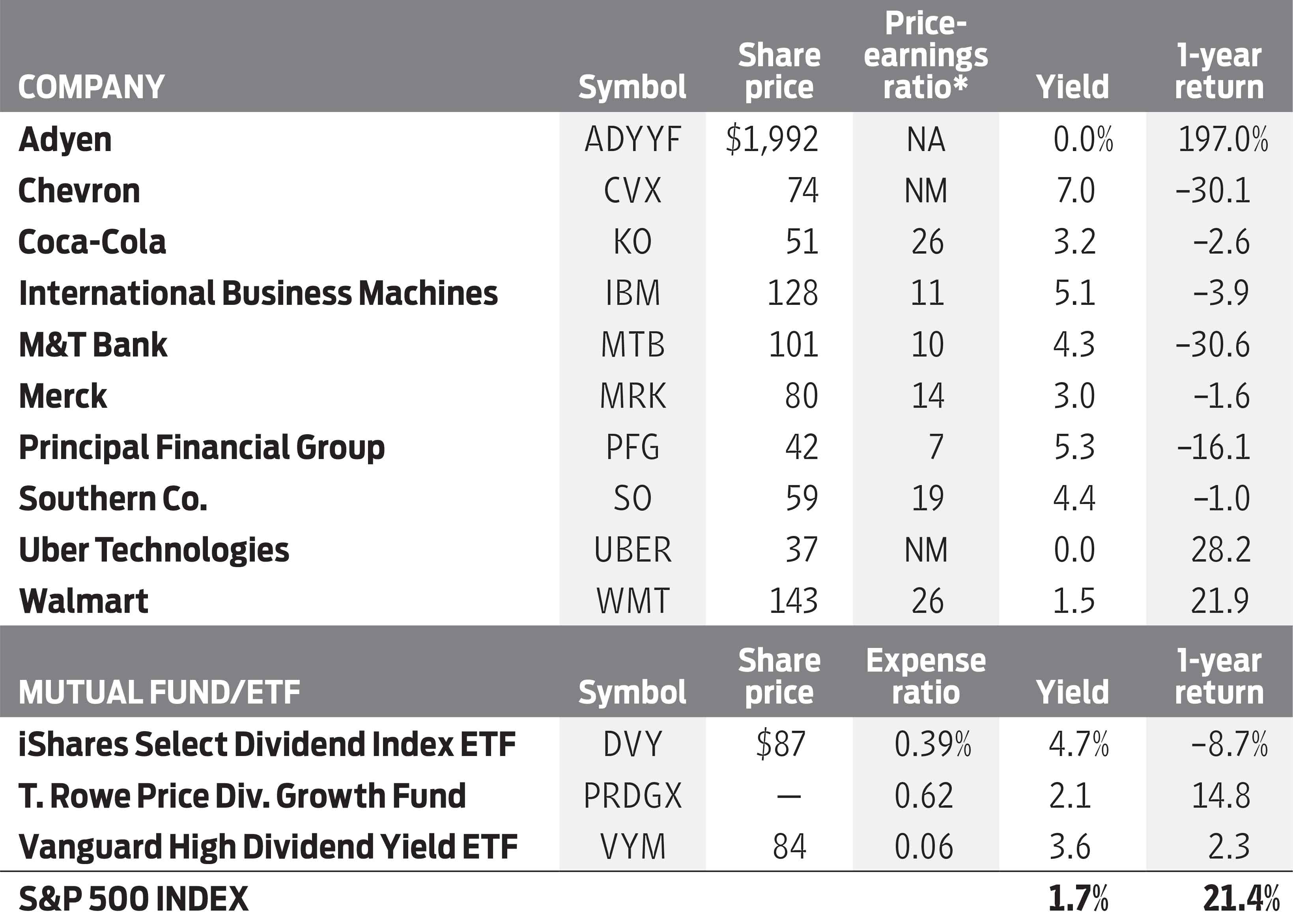

In their new book, Radical Uncertainty, British authors John Kay and Mervyn King write that “good strategies for a radically uncertain world avoid the pretense of knowledge.” Kay, an Oxford University economist, and King, the former governor of the Bank of England, are establishment figures turned radical innovators. Their first lesson for investors: Trust your gut. Buy companies that you believe have terrific ideas even if you are not sure how they will work out in the future. Good examples are Uber Technologies (symbol UBER, $37), which, despite a COVID setback, is creating a transportation revolution; Walmart (WMT, $143), which is figuring out how to blend traditional and online retailing; and fintech firms such as Netherlands-based Adyen (ADYYF, $1,992), a booming global payments platform. (Stocks I like are in bold; prices are as of October 9.)

The second lesson is to be a long-term stock investor. The recovery of the stock market from its COVID crash in February and March was unusually dramatic, but markets do always come back. The Dow fell by about half from its September 2007 high to its March 2009 low, but it regained its 2007 level in less than four years and then doubled by 2019. Governments today have the tools to revive economies: zero interest rates, central bank bond purchases and cash dropped into the markets as if by helicopter. Someday, perhaps, we will pay for these actions, but so far, so good.

Pocket the cash. The third lesson is to collect the cash while you can—that is, buy stocks that pay good dividends. They abound these days in diverse sectors, and it is not hard to find companies that yield twice what 30-year Treasury bonds pay. Some examples: Principal Financial Group (PFG, $42), the insurer and asset manager, yielding 5.3%; International Business Machines (IBM, $128, 5.1%); utility Southern Co. (SO, $59, 4.4%); pharmaceutical firm Merck (MRK, $80, 3.0%); M&T Bank (MTB, $101, 4.3%); Chevron (CVX, $74, 7.0%); and Coca-Cola (KO, $51, 3.2%).

Also consider iShares Select Dividend Index (DVY, $87), an exchange-traded fund whose portfolio consists of stocks that have increased their payouts in each of the past five years; Vanguard High Dividend Yield (VYM, $84), an ETF with a portfolio yielding 3.6% and an expense ratio of just 0.06%; or T. Rowe Price Dividend Growth (PRDGX), a mutual fund that has returned an annual average of 13.3% over the past five years.

Knight realized that to succeed as an entrepreneur, you have to take a chance on the unknown. The same is true for investors. Ignorance is a necessary companion for any investor. The good news, however, is that markets pay you handsomely for your courage in facing uncertainty.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, a public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. Of the stocks mentioned in this column, he owns Uber. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments In a Time of Turbulence.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)

The Most Tax-Friendly States for Investing in 2025 (Hint: There Are Two)State Taxes Living in one of these places could lower your 2025 investment taxes — especially if you invest in real estate.

-

Bond Basics: Zero-Coupon Bonds

Bond Basics: Zero-Coupon Bondsinvesting These investments are attractive only to a select few. Find out if they're right for you.

-

Bond Basics: How to Reduce the Risks

Bond Basics: How to Reduce the Risksinvesting Bonds have risks you won't find in other types of investments. Find out how to spot risky bonds and how to avoid them.

-

What's the Difference Between a Bond's Price and Value?

What's the Difference Between a Bond's Price and Value?bonds Bonds are complex. Learning about how to trade them is as important as why to trade them.

-

Bond Basics: U.S. Agency Bonds

Bond Basics: U.S. Agency Bondsinvesting These investments are close enough to government bonds in terms of safety, but make sure you're aware of the risks.

-

Bond Ratings and What They Mean

Bond Ratings and What They Meaninvesting Bond ratings measure the creditworthiness of your bond issuer. Understanding bond ratings can help you limit your risk and maximize your yield.

-

Bond Basics: U.S. Savings Bonds

Bond Basics: U.S. Savings Bondsinvesting U.S. savings bonds are a tax-advantaged way to save for higher education.

-

Bond Basics: Treasuries

Bond Basics: Treasuriesinvesting Understand the different types of U.S. treasuries and how they work.