The Coin Shortage: How Can You Help?

An increase in online shopping and e-payments has led to a coin crunch.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

First it was toilet paper, then yeast. Clorox wipes are still hard to find. But few predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic would also trigger a nationwide coin shortage.

Actually, it’s not really a shortage, because there are plenty of nickels, dimes and quarters languishing in sock drawers, jelly jars and overstuffed wallets. The problem is that Americans are making fewer cash purchases, which has reduced the number of coins in circulation, says Cyndie Martini, president and chief executive officer of Member Access Processing, which processes debit card payments for credit unions. Consumers are making more purchases online, and when they do venture out to shop, many prefer using debit cards, credit cards or contactless payments with their phones.

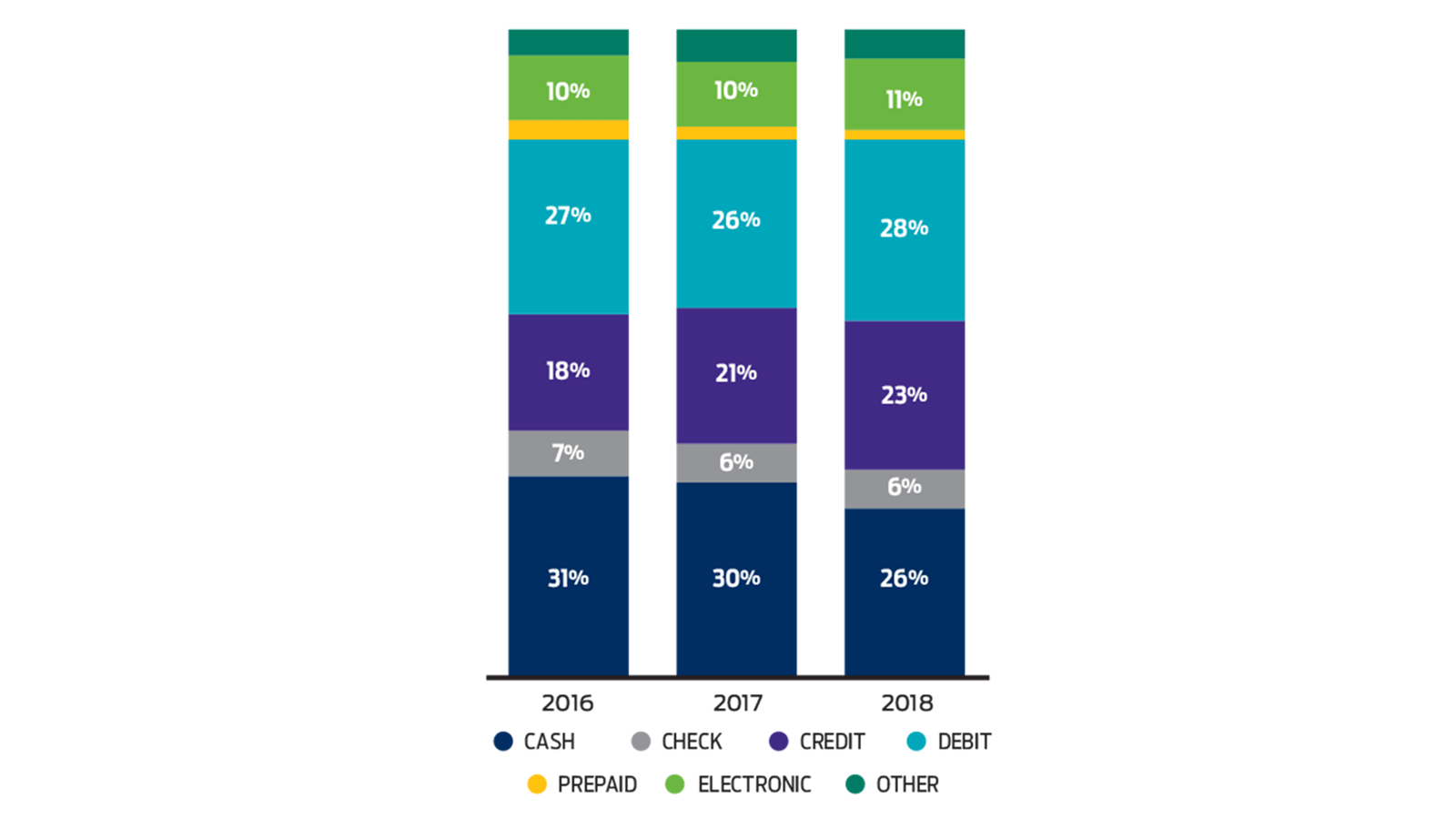

Analysts say the pandemic has accelerated a shift away from cash payments in favor of electronic transactions (see COVID-19 Speeds the Cashless Transition). In 2018, consumers used cash for 26% of their payments, down from 30% in 2017, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. A survey by the Pew Research Center found that 29% of Americans said they made no cash purchases in a typical week in 2018, up from 24% in 2015.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

To cope with the coin shortage, many retailers are asking customers who use cash to pay the exact amount. At Kroger supermarkets, cash purchases are rounded up and the excess is added to a store loyalty card or donated to charity.

The U.S. Mint recently called on Americans to put their spare change back in circulation. “The coin supply problem can be solved with each of us doing our part,” the Mint said in a statement.

If you have a lot of change lying around your house, you have some options:

Take it to your bank. Banks that once looked askance at customers who hauled in coffee cans full of quarters and dimes are now happy to roll up your change. One Wisconsin bank even offered $5 for every $100 in coins turned in (the promotion has since ended). If your stash is too big to take to the drive-through window, you may need to make an appointment, because many bank lobbies are closed due to the pandemic.

You can add the money to your emergency savings account. Or, if that account is already funded, use it to pay off any outstanding credit card bills. You’ll get an instant return of 15% or better, which is a lot more than the money was earning in your sock drawer.

Take your change to a coin kiosk. Coinstar kiosks, with more than 20,000 locations around the world, will exchange your coins for cash for an 11.9% service fee. But if you opt instead for a gift card, you won’t have to pay any fees. Participating retailers include Amazon, Lowe’s, Home Depot and Starbucks.

Give the money to charity. Coinstar also lets you deposit your change in the account of a participating charity. Go to coinstar.com/charitypartners to search for kiosks in your area. If you deposit your change in your bank account, another option is to write a check to your favorite charity. Taxpayers who claim the standard deduction can deduct up to $300 in cash contributions in 2020.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.

-

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market Today

Dow Leads in Mixed Session on Amgen Earnings: Stock Market TodayThe rest of Wall Street struggled as Advanced Micro Devices earnings caused a chip-stock sell-off.

-

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without Overpaying

How to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics Without OverpayingHere’s how to stream the 2026 Winter Olympics live, including low-cost viewing options, Peacock access and ways to catch your favorite athletes and events from anywhere.

-

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for Less

Here’s How to Stream the Super Bowl for LessWe'll show you the least expensive ways to stream football's biggest event.

-

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't Need

9 Types of Insurance You Probably Don't NeedFinancial Planning If you're paying for these types of insurance, you may be wasting your money. Here's what you need to know.

-

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online Bargains

Amazon Resale: Where Amazon Prime Returns Become Your Online BargainsFeature Amazon Resale products may have some imperfections, but that often leads to wildly discounted prices.

-

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should Know

What Does Medicare Not Cover? Eight Things You Should KnowMedicare Part A and Part B leave gaps in your healthcare coverage. But Medicare Advantage has problems, too.

-

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in Retirement

15 Reasons You'll Regret an RV in RetirementMaking Your Money Last Here's why you might regret an RV in retirement. RV-savvy retirees talk about the downsides of spending retirement in a motorhome, travel trailer, fifth wheel, or other recreational vehicle.

-

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026

Roth IRA Contribution Limits for 2026Roth IRAs Roth IRAs allow you to save for retirement with after-tax dollars while you're working, and then withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free when you retire. Here's a look at 2026 limits and income-based phaseouts.

-

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnb

Four Tips for Renting Out Your Home on Airbnbreal estate Here's what you should know before listing your home on Airbnb.

-

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute Vacation

Five Ways to a Cheap Last-Minute VacationTravel It is possible to pull off a cheap last-minute vacation. Here are some tips to make it happen.

-

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?

How Much Life Insurance Do You Need?insurance When assessing how much life insurance you need, take a systematic approach instead of relying on rules of thumb.