How to Decide If It’s Time for a Career Change

The pandemic has prompted many workers to consider more fulfilling jobs. These people made it work.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

COVID-19 upended the job market in multiple ways. Millions of Americans lost their jobs, saw their salaries reduced or were sent out of the office to work from home. But as uncertainty surrounding the pandemic continues, many workers have decided it’s time for a change. In a January survey of unemployed Americans, Pew Research Center found that 66% have seriously considered pursuing a different career because of the pandemic. One-third said they had enrolled in training programs or other educational endeavors to sharpen their skills.

The internet is filled with tales of restaurant workers, hairstylists and corporate employees who have jumped ship in hopes of finding more meaningful employment. But switching careers isn’t easy, and figuring out what your new gig will be is a job all by itself. In addition to retraining, you may need to rebuild your network—which may take more time than usual because the pandemic has limited the ability to meet people in person.

Career changers must also adapt to the permanent changes the pandemic brought to office culture. Flexible schedules, remote work and virtual hiring are here to stay. And if you’re an older worker interested in switching careers, you should get comfortable with the possibility that you’ll report to a younger supervisor.

We’ve profiled four people who have made a career switch, including two who say the pandemic, along with recent social upheaval, gave them the courage to take the leap.

A Model Enters the Police Academy

What do a model/retail store manager and a police officer have in common? They both walk a beat. But in all seriousness, for Ponce Garner, 29, of Ypsilanti, Mich., who was recently accepted into the Wayne County Sheriff’s Jailer’s Academy and the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards, both occupations have a common theme: customer service.

With protests erupting across the country after the death of George Floyd and other instances of police violence, Garner wanted to change how his community views police. His goal is to be one of the police officers who genuinely care about the community they’re patrolling.

Like many people, Garner had a high school teacher who helped nudge him toward his dream career. After he wrote about his goal of becoming a police officer for his sophomore English class, his teacher introduced him to his sister, an agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The conversation helped seal his conviction that policing was the right career path for him.

However, his family urged him to consider a less dangerous job, so he turned to fashion, his second love. He studied fashion at Eastern Michigan University while he worked his way up to becoming a comanager at a Guess store in Auburn Hills, Mich. In 2018, he moved to Atlanta, where he managed another Guess store and started modeling, working five shows for Atlanta Fashion Week.

But policing never left Garner’s mind. He moved back to Michigan in April 2020 and applied to the police academy via the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office and the Detroit Police Department. Applications were put on hold because of the pandemic, but in June, Garner heard back from the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office. Next came health screenings, background checks and a final interview.

In July, Garner was notified that his first round of training would start in August. He has to complete nine weeks of correctional officer training, followed by six months of standard police training. The career change couldn’t have come at a better time because, he says, working in retail and modeling doesn’t leave a lot of room to move up. Moving into policing will eventually provide him with better pay and more opportunities to advance. But even dream jobs come with challenges.

Garner must hit the gym consistently to prep for the academy’s physical requirements. He also needs to prepare his family for his move into a career field they originally discouraged. And once the correctional training is complete, Garner will be required to work in the Wayne County jail for a year while simultaneously going to regular police academy training. After his year is up, he will be eligible to transfer into another department. While the prospect of working at a jail would make some folks anxious, Garner says he’s ready.

“I’ve talked to former Wayne County officers about their experiences, and they say working at the jail isn’t as crazy as it sounds,” he says. Garner has also been assured that the county provides mental health resources if he becomes overwhelmed by the job. Garner is expected to graduate from the academy in February 2022.

A Reporter Joins the Mental Health Field

Melanie Martin Ebel, 39, of Toledo, is no stranger to switching careers. Before she started working in the mental health field, she was a sports journalist for a newspaper in a small Ohio town, where she was hired in the early 2000s after graduating from Ohio State University with a bachelor’s degree in journalism. Although she enjoyed her time at the university’s newspaper, even working her way up to be its editor in chief, journalism in the real world proved to be a disappointment.

“They very much had the small-town mentality of, ‘Oh gosh, we have this woman who’s writing sports,’ and there was a lot of resistance,” she says. She says she also experienced sexual harassment from football coaches and other people she covered.

Deciding on what she wanted to do next didn’t take long, because Ebel had gained extensive experience in the field of mental health during her teenage and college years. However, she feared that she had wasted her time by majoring in journalism, and she worried that potential employers would doubt her commitment to her new chosen field.

“People would question why I didn’t get a degree in the mental health field if that’s what I wanted to do,” she says. And it didn’t help that she was jumping from one low-paying field to another.

But she persevered and started at Unison Health, an outpatient community mental health clinic, in 2009; she eventually earned her master’s degree in social work in 2017. By the time the pandemic hit in 2020, Ebel was working as a day treatment and hospitalization program manager at Unison and had completed Ohio’s work requirement to apply for an independent clinician license (which, along with her master’s, will qualify her for management positions and allow her to open her own practice down the road).

Like many Americans, Ebel worked at home during the pandemic and met with clients and coworkers over video calls. But with her four kids, ages 4 months to 12 years, staying home because of day care closures and virtual school, Ebel says she thought it was time for another change. She asked her supervisor if she could reduce her hours so she could focus more on her children. “I didn’t feel like I was giving 100% to anything, and I knew I needed to recommit,” she says. Her agency’s management and her husband supported her decision.

Now, Ebel works part-time, helping to oversee the day treatment and partial hospitalization program she used to manage full-time, and she continues to offer individual therapy. Although Ebel took a pay cut when she reduced her hours, she and her husband are saving money on day care bills. And even her 12-year-old daughter likes her being at home—most of the time.

“There’s a lot of stress being home with the kids—but it’s the stress that I would choose,” she says. “We have opportunities to make really good memories.”

A Financial Analyst Becomes a Career Coach

Tracy Akresh Stone, 47, of San Francisco, got her first certification in career coaching 15 years ago, but she had been coaching folks informally long before that. Early in her career as an equity research analyst on Wall Street, she remembers counseling her cubicle partner, a more senior analyst, after the analyst was unable to present her ideas at an important meeting.

“I remember giving her this pep talk, telling her what to do,” Stone says. “She was so much more experienced, and yet she needed a coach.” After that, coworkers regularly came to Stone for advice on how to manage their careers.

Eventually, Stone realized she didn’t want her boss’s job and decided to take some of her own advice. But she didn’t leave corporate America in one big leap. First, she tried different roles outside of equity research, even working her way up to director of finance at a start-up. The position was short-lived, however, and she left the start-up and corporate America for good in 2011. Because she had started career coaching on the side, she already had a clientele and a savings cushion.

“I tell all my clients that they really need to sit down with their finances and figure out how they’re going to make the career switch work,” she says. “It can take time to ramp up, especially if you’re going solo.” That meant Stone had to learn how to market herself.

Now, Stone has a steady roster of clients, from large corporations to small start-ups that bring her in to work with managers who are seeking to be more engaged in their careers. And although the pandemic initially affected her business, companies have now started hiring her to help their leaders manage remote teams.

Leaving Corporate Life for a Nonprofit

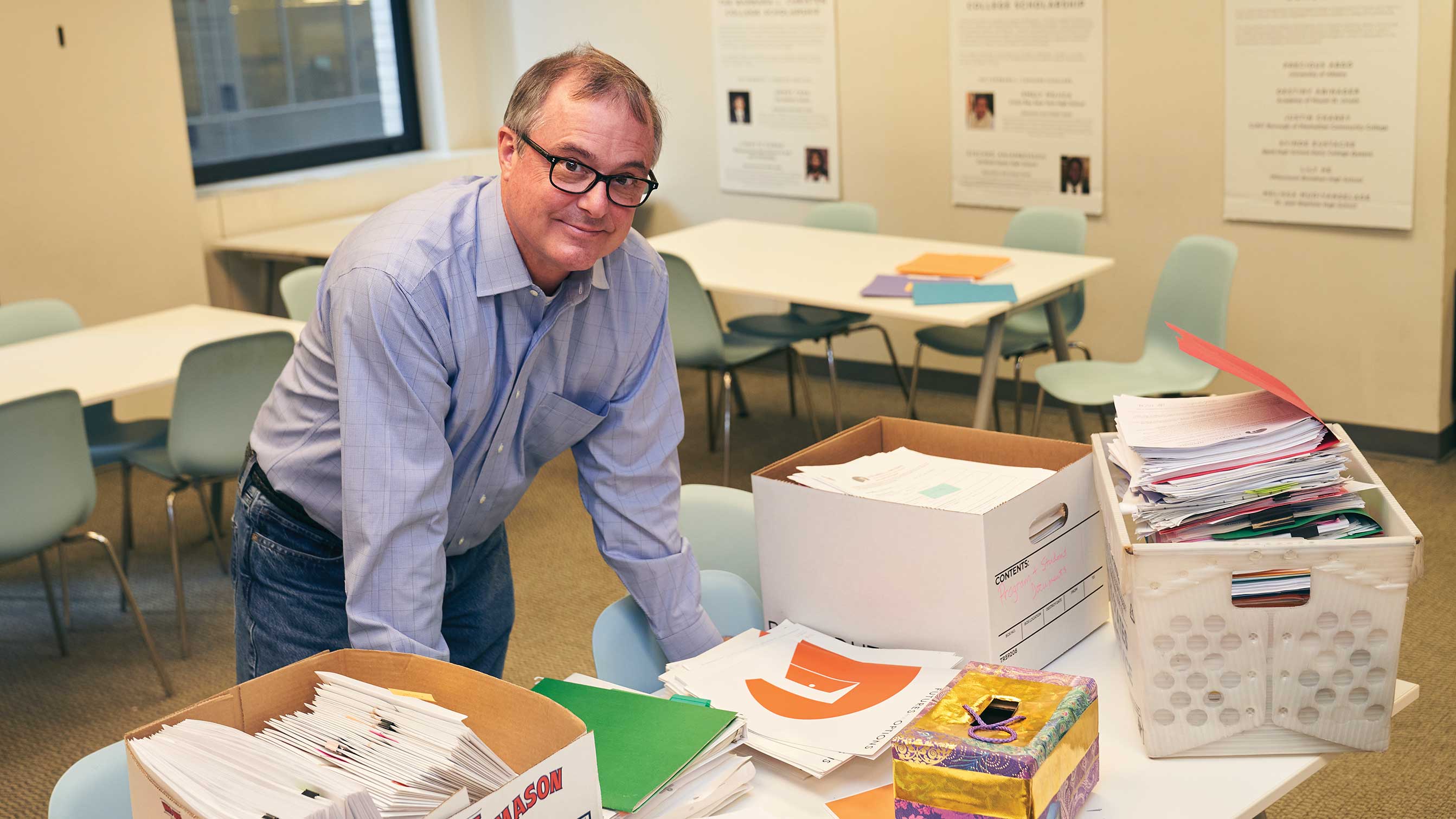

David Pfeifer, 61, remembers a time when he knew everything there was to know about technology. As a semiconductor engineer during the 1980s, he says he could manually expand the RAM—or memory—of his desktop computer, leaving peers and colleagues to constantly ask, “Can you show me how to do that?”

But four decades later, the tables have turned. As the director of finance and administration at Futures and Options, a nonprofit organization that places minority and other underserved New York City high school students into paid internships, he’s surrounded by a new generation of technologically savvy and gifted youth.

“This generation has just grown up with technology in a way that I haven’t,” Pfeifer says. “Every day, I am in awe of what’s so natural for them.”

Pfeifer spent most of his career in the private sector, moving from an engineering job at a semiconductor wafer fabrication plant to chief financial officer of an e-commerce company that sells women’s bathing suits. He has also worked as an adjunct professor at Columbia Business School in New York, where he received his MBA.

As Pfeifer neared retirement age, he and his wife struggled to decide what they wanted to do next. “At this point, it’s not so much a financial decision. We’re not working to get to some number in the bank and then boom, that’s the day we retire,” says Pfeifer. “Are we having fun working?” is the better question to ask, he says.

One day, his wife stumbled upon an article in the New York Times about Encore.org, an organization that matches veteran professionals with positions in the nonprofit sector. “I knew nothing about [nonprofits] from the private sector. I didn’t even know where to start,” Pfeifer says.

After an extensive application process, Encore matched him with Futures and Options. Because the nonprofit centers around youth mentorship, working there has introduced him to people who have dramatically different life experiences than the people he encounters near his Upper West Side residence.

“Working with younger people makes you young again, because it exposes you to a whole different level of energy,” Pfeifer says.

Pfeifer joined Encore in January 2020, just weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic halted its in-person operations. But he says he has been surprised by how quickly Futures and Options was able to adapt to remote work. In fact, transitioning to remote career development coursework helped more students finish the program.

To adjust to the learning curve of a new industry and working environment, it’s important to understand why you want to pursue a career change and what you can contribute to a new sector, Pfeifer says. He believes veterans of the private sector can become overconfident after years of calling the shots. In his case, he says, humility and listening to those with more experience helped him adapt to his new role.

Pfeifer says he continues to enjoy assisting with the nonprofit’s financial reports, as well as helping it provide internships to the program’s high school students. “There is a unique quality of doing something like this,” Pfeifer says. “It’s different from just producing a low-cost product or a very good product for a demanding customer base.”

Kip Tip: Get Help From a Coach

Whether you’re thinking of switching careers or you’re just interested in a new job with your current employer, identify the skills you have and how they can help the organization. If you need help figuring that out, consider consulting a career coach.

Start by visiting your alma mater’s alumni website, which may provide a list of career coaches that partner with the university. When looking for a coach, make sure their experience aligns with your own goals. A good coach will assess your strengths and your background to help you evaluate your career decisions, says career coach Daryll Bryant.

Alternatively, you can look for group coaching programs. The Grand offers group coaching programs on topics ranging from becoming an effective manager to making a career transition. Programs usually run for 14 weeks. The cost ranges from $1,200 to $2,400, depending on the program. To view current offerings, go to www.thegrand.world/experience.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Rivan joined Kiplinger on Leap Day 2016 as a reporter for Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine. A Michigan native, she graduated from the University of Michigan in 2014 and from there freelanced as a local copy editor and proofreader, and served as a research assistant to a local Detroit journalist. Her work has been featured in the Ann Arbor Observer and Sage Business Researcher. She is currently assistant editor, personal finance at The Washington Post.