How Would Raising the Social Security Retirement Age to 69 Affect You?

Raising the Social Security retirement age to 69 is floated from time to time. Here's how it would affect your benefits if it ever happened.

Ellen B. Kennedy

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

The trust fund that pays Social Security retiree benefits is projected to run out of money in the first quarter of 2033. At that point, if nothing is done, the fund will only cover 77% of scheduled benefits.

With the prospect of Social Security facing insolvency in the coming years, raising the Social Security age to 69 is one proposal that makes the rounds from time to time. After all, in the early 1980s, the age was gradually increased from 65 to 67, so it's not a stretch to raise it again.

But raising it to 69 would be bad news for many U.S. workers who are sticking it out to 67. That’s the age when you can retire and start collecting your full Social Security benefits if born in 1960 or beyond. Sure, you can claim early benefits at 62, but if you do so, your payments will be reduced by 30%.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Is raising the Social Security retirement age inevitable?

While there are currently no policies on the books or legislation in the works, raising the Social Security retirement age may be a foregone conclusion if nothing is done to fix it.

“Social Security was never meant to fund 30 years of retirement, so it makes sense that the full retirement age increases with time,” says Eric Ludwig, program director for the Retirement Income Certified Professional (RICP®) Program at the American College of Financial Services.

“That's why we need to focus on expanding lifetime income options in retirement savings plans to give Americans more flexibility in how they create sustainable retirement income.”

But what if the full retirement age (FRA) were raised to 69, as some politicians and policymakers have called for? Would it be enough to keep Social Security afloat, and what would it mean to American workers?

Would my Social Security check be lower?

Extending the retirement age to 69 might boost Social Security’s coffers. But this move would also leave workers with two unpalatable choices: work longer or get lower benefits.

In a recent letter to Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected the impacts of raising the retirement age to 69.

"For people born in the 1970s, ... the average retirement benefits for workers who claimed benefits at age 65 would be 13 percent less than the average benefits they would receive under current law".

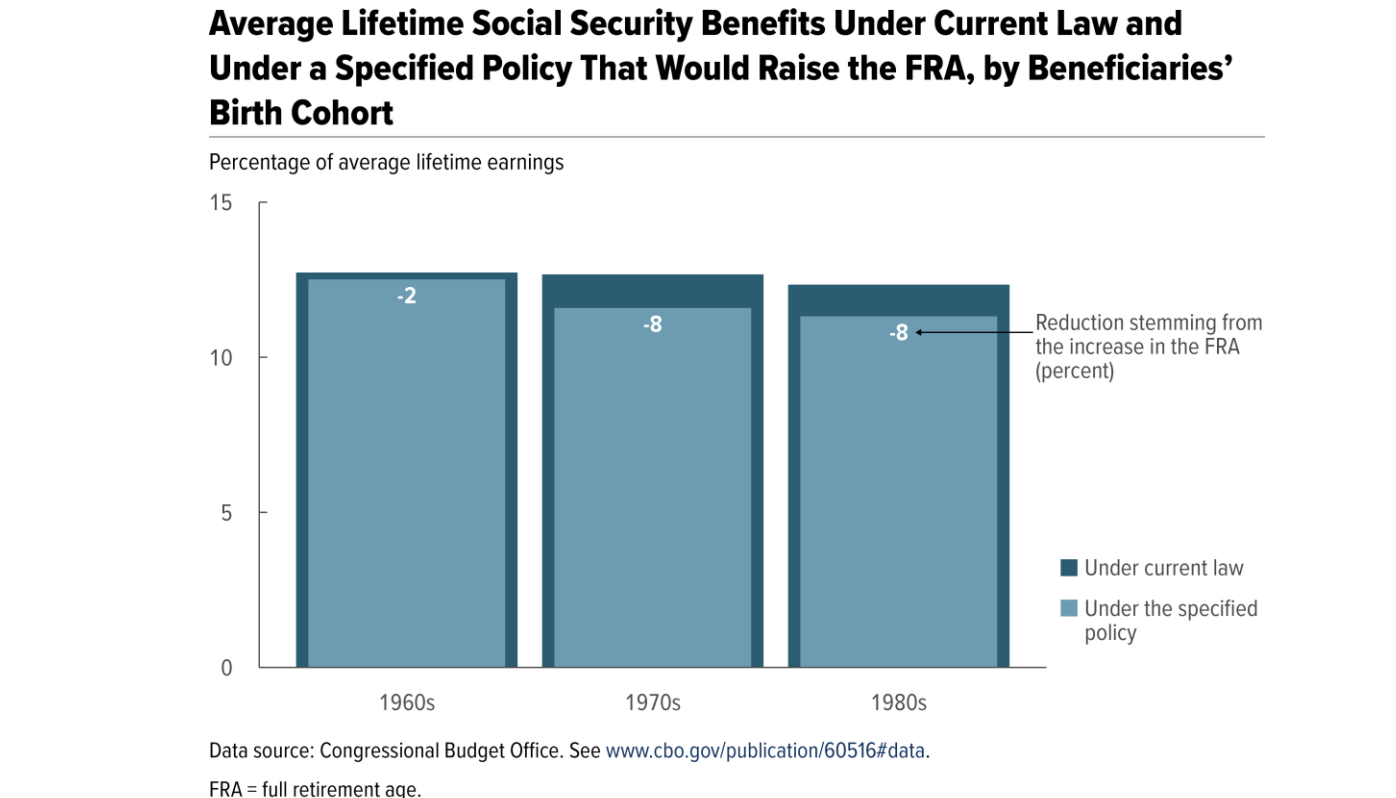

The average lifetime reduction in benefits would hit younger workers harder. For people born in the 1960s, this change would translate to only a 2% overall average lifetime decline in benefits.

However, those born in the 1970s or 1980s would receive 8% lower lifetime benefits on average, as shown in the chart below.

What if I take Social Security early or late?

Increasing the full retirement age for most retirees from 67 to 69 would change the retirement planning equation. While the same general rules would apply, workers would have to adjust their retirement timing or settle for lower benefits.

For workers born after 1959, the current full retirement age is 67. That's when you can expect 100% of your benefits. Under the scenario studied by the CBO, you could still retire as early as 62, but your Social Security check would be even lower than under current law.

If you waited until the hypothetical new full retirement age of 69, you would get 100% of benefits, but for a shorter period. Those who might want to get the biggest payout and delay collecting until age 72 (up from 70 under current law) would receive less of a benefit increase.

One problem with the proposed changes is the lack of equity between office workers and those who do physically taxing jobs. The latter group often has to retire early as their jobs wear out their bodies or are unsuitable for older workers.

“We're essentially telling construction workers, nurses, and factory workers they need to keep lifting, bending, and standing for an extra two years,” says Ludwig. “The cruel irony is that these are often the same workers who have shorter life expectancies and would collect benefits for fewer years anyway.”

Some of these workers will be forced to find ways to cover the shortfall, which could mean cutting their budget or downsizing, getting part-time work, or tapping the Social Security Disability Insurance program. The latter option would erode some of the projected cost savings from raising the full retirement age, noted Mitchell.

Would the proposal fix Social Security?

Social Security is funded primarily in two ways. The first and most significant is from payroll taxes paid by workers and employers.

The second is from interest on the trust fund, where payroll taxes are housed. This system worked well until the 1970s and early 1980s, when it began running deficits.

In 1983, Congress reformed the system by increasing payroll taxes and gradually raising the full retirement age. This effort was a success, leading to trust fund surpluses until about 2009, according to the nonpartisan Peterson Foundation.

The U.S. is again facing an underfunded Social Security system. People are living longer, requiring more years of benefits, while the number of working-age contributors to payroll taxes isn't keeping up. Other structural reasons contribute to the shortfall.

The CBO projects that the trust fund will be exhausted by 2034. At that time, Social Security would rely on payroll taxes to pay benefits, which would be diminished by 21%.

It seems counterintuitive, but the CBO estimates that, under the proposal, the trust fund would still be insolvent in 2034. However, the rate at which payroll taxes can fund the system would improve over 75 years.

That deficit would decrease from 4.3% to 3.3% — a total reduction of 24%. So, this proposal would help over the long term, but it won't be enough to fix Social Security.

Could raising the Social Security retirement age prompt more saving?

Working longer is probably not on your to-do list, but if you are forced to do so because the retirement age is extended, it could be positive if you are healthy and can still perform your job.

After all, it gives you two additional years to save. If you are an older worker, it means two more years you can take advantage of catch-up contributions in your company-sponsored retirement savings accounts.

It could also bolster your savings. Knowing your Social Security payments will be lower may prompt you to save more while you’re working.

“On one hand, extending the full retirement age to 69 could motivate better saving habits — when people realize they need to fund a longer period before Social Security begins, we see increased engagement with retirement planning,” says Ludwig.

“However, the concerning reality is that many Americans already struggle to understand Social Security claiming strategies. Adding more complexity to the system might lead to suboptimal decisions, particularly among those who feel forced to claim early benefits at permanently reduced rates.

The key isn't just changing the age — it's about improving financial literacy alongside any policy adjustments.”

Related content

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Donna Fuscaldo is the retirement writer at Kiplinger.com. A writer and editor focused on retirement savings, planning, travel and lifestyle, Donna brings over two decades of experience working with publications including AARP, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Investopedia and HerMoney.

- Ellen B. KennedyRetirement Editor, Kiplinger.com

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're Rich

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're RichSome frugal habits are worth it, no matter what tax bracket you're in.

-

Why Picking a Retirement Age Feels Impossible (and How to Finally Decide)

Why Picking a Retirement Age Feels Impossible (and How to Finally Decide)Struggling with picking a date? Experts explain how to get out of your head and retire on your own terms.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.

-

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look Like

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look LikeThis is when you should be shifting your focus from growing your portfolio to designing an income and tax strategy that aligns your resources with your purpose.

-

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your Stress

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your StressTo be confident about retirement, consider building a safety net by dividing assets into distinct layers and establishing a regular review process. Here's how.

-

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?

Your Adult Kids Are Doing Fine. Is It Time To Spend Some of Their Inheritance?If your kids are successful, do they need an inheritance? Ask yourself these four questions before passing down another dollar.

-

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)The key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)Couples who talk openly about finances, including estate planning, are more likely to head into retirement joyfully. How can you get the conversation going?

-

We're 62 With $1.4 Million. I Want to Sell Our Beach House to Retire Now, But My Wife Wants to Keep It and Work Until 70.

We're 62 With $1.4 Million. I Want to Sell Our Beach House to Retire Now, But My Wife Wants to Keep It and Work Until 70.I want to sell the $610K vacation home and retire now, but my wife envisions a beach retirement in 8 years. We asked financial advisers to weigh in.