New Rules for Inherited IRAs Could Leave Heirs With a Hefty Tax Bill

Thanks to recent changes in the law on inherited IRAs, your tax bill from any inheritance could be larger than you expect.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

New rules for inherited IRAs could leave some heirs with a hefty tax bill. In the first quarter of 2023, Americans held more than $12 trillion in IRAs. If your parents saved diligently throughout their lives, there’s a good chance you’ll inherit some of that money.

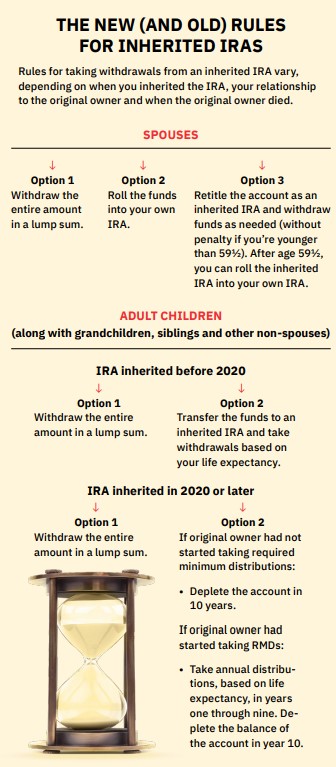

But before you quit your day job — or buy a Maserati — make sure you factor in the amount of your inheritance you’ll have to share with Uncle Sam. Thanks to recent changes in the law, along with a new interpretation of those changes from the IRS, your tax bill could be larger than you expect. Beneficiaries of traditional IRAs have always had to pay taxes on inherited accounts, but before 2020, you could minimize the tax bill by extending withdrawals over your life expectancy. If you inherited an IRA before 2020, you can still take advantage of that strategy to stretch out withdrawals — and taxes — over your life expectancy.

But the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, which was signed into law in 2019, put an end to this tax-saving strategy for most adult children, grandchildren and other non-spouse heirs who inherit a traditional IRA on or after January 1, 2020. Those heirs now have two options: Take a lump sum and pay taxes on the entire amount, or transfer the money to an inherited IRA that must be depleted within 10 years after the death of the original owner. (The clock starts the year after the original owner dies, and the time runs out on December 31 of the 10th year following the year of the owner’s death, so you actually have a little more than a decade to empty the account. For example, if you inherited an IRA in 2020, year one is 2021 and the account needs to be cleaned out by December 31, 2030.)

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The 10-year rule also applies to inherited Roth IRAs, but with an important difference: You are not required to pay taxes on the withdrawals, and you don’t have to take required minimum distributions (RMDs) because the original owner didn’t have to take them, either. That gives you plenty of flexibility with respect to withdrawals, but if you can afford to wait until year 10 to deplete the account, you’ll enjoy more than a decade of tax-free growth.

Initially, tax experts and financial planners believed that non-spouse heirs who inherited a traditional IRA would be in compliance with the law as long as they depleted the account in 10 years. That would provide them with the ability to minimize withdrawals during high-income years and take out more when their income declined — for example, during their retirement years. However, guidance issued by the IRS in February 2022 torpedoed that strategy for some heirs. If your parent died before he or she was required to take minimum distributions, you can withdraw the money at any time, in any amount you choose, as long as the account is depleted in year 10. But under the IRS interpretation of the SECURE Act, if your parent died on or after the date he or she was required to take minimum distributions, you must take RMDs based on your life expectancy in years one through nine and deplete the balance in year 10. Basically, once the original owner has started taking RMDs, you can’t turn them off, says Ed Slott, founder of IRAhelp.com, although the IRS doesn’t require you to withdraw the same amount as your parent would have been required to withdraw.

In response to confusion about the proposed rules, the IRS waived penalties for those who did not take RMDs that should have been taken from inherited IRAs in tax years 2021 and 2022, and in July, extended that relief for the tax year 2023. However, you may be required to start taking distributions in 2024, so it's not too soon to plan. The penalty for missing a distribution is 25% of the amount you should have withdrawn. (The penalty will be reduced to 10% if you make up the missed RMD within two years.)

Inherited IRAs: Calculate how much to withdraw

If you’re required to take a minimum distribution from an inherited IRA, use the factor in the IRS Single Life Expectancy Table (you can find it in IRS Publication 590-B) to figure out how much you must withdraw. You’ll use the factor for your age this year and the balance of the IRA at the end of the previous year to calculate your distribution.

For example, if you’re 50 and inherited a traditional IRA from someone other than your spouse with a balance of $500,000 at the end of 2022, you would divide the balance by a life expectancy factor of 36.2, for a required minimum withdrawal of $13,812.

You can, of course, withdraw more than the minimum — and in some instances, that may be a tax-savvy strategy. Distributions from a traditional IRA are taxed as ordinary income and subject to federal and, in some cases, state taxes. Even if you have the option of waiting until year 10 to empty the account, you could end up with a large distribution that will vault you into a larger tax bracket. For example, if you inherit an IRA worth $1 million and wait until year 10 to take a withdrawal, “you’ll have a mammoth tax bill,” Slott says.

Unless you plan on cashing out, you need to open an inherited IRA account.

Even if you take RMDs each year, you could end up with a large taxable withdrawal when you reach year 10 and are required to withdraw the remaining funds in the account, says Sallie Mullins Thompson, a certified financial planner and certified public accountant in Washington, D.C. Mullins Thompson advises her clients who are non-spouse beneficiaries to estimate their annual income over the next 10 years in order to calculate how much to withdraw each year. She factors in upcoming events that could affect clients’ income, such as filing for Social Security benefits or taking RMDs from their own retirement accounts, in figuring out how much they should withdraw. If a client has a year in which his or her income declines — they’re between jobs, for example — she’ll recommend taking a larger distribution. With the help of a financial planner, you should be able to estimate how much you can withdraw while remaining within your existing tax bracket. If you’re not sure what your income in the future will be, another strategy is to withdraw 10% from your account every year. That will be sufficient to avoid IRS penalties and enable you to avert a large taxable distribution in year 10.

How to manage your inherited IRA

Unless you plan on cashing out an inherited IRA — which, in the case of a traditional IRA, will trigger taxes on the entire amount — you need to open an inherited IRA account. You can’t leave the money in the original owner’s account, and unless you’re a surviving spouse, you can’t roll the money into your own IRA. Instead, you must request a trustee-to-trustee transfer of funds to your inherited IRA. This is critical because if you receive a check instead, you’ll be taxed on the entire amount — it doesn’t matter if you turn around and reinvest the funds in an IRA.

Even if you set up an inherited IRA with a financial institution that’s home to your other retirement accounts, your inherited IRA will occupy a room of its own. It will remain in the name of the original owner, with you listed as the beneficiary, and it can’t be merged with other retirement accounts. Typically, the financial institution will title the account in this manner: John Smith (IRA, deceased on 1/5/2021) FBO Michael Smith, beneficiary.

Once you’ve set up your inherited IRA, you can invest the money in any way you choose, based on your goals and risk tolerance. Taxes on the funds will be deferred until you take distributions, so even if you think you may empty the account in the near future, transferring funds to an inherited IRA gives you more flexibility. That said, be prepared to make a few phone calls when transferring funds to your inherited IRA. In addition to the application for an inherited IRA account, you may need to produce a death certificate and documents verifying that you’re the beneficiary. If the original owner died before taking all or part of an RMD, you’re required to withdraw the remaining amount of the required distribution by December 31 of the year of death.

The year-of-death RMD will be calculated as if the original owner were still alive, usually based on the IRS Uniform Lifetime Table. In most cases, you can arrange to take the distribution after you’ve transferred the assets to your inherited IRA. If the IRA had multiple beneficiaries, you may decide to divide the year-of-death RMD equally, but the IRS doesn’t care how it’s allocated as long as the RMD is taken. The payout will be reported on your tax return (as well as the tax returns of any other beneficiaries who received payouts), not the estate tax return.

Inherited IRAs: Options as a spouse

If you inherit an IRA from your spouse, you have more flexibility than non-spousal heirs, but you’ll still have some important decisions to make. Your options:

- Treat it as your own IRA

In this case, the IRA will be treated as if you had owned it all along, with the same minimum withdrawal requirements. - Roll the IRA into your own new or existing IRA

Once you’ve rolled over the funds, you can postpone withdrawals until you reach the age at which you must take the required minimum distributions — 73 in 2023, increasing to 75 in 2033. You’ll have this option even if your spouse had started taking RMDs, although if your spouse died before taking a required distribution, you must take an RMD for that year. After you’ve completed the rollover, you can also convert some of the funds in your traditional IRA to a Roth. This strategy may be worth considering if you have sufficient funds outside the IRA to pay taxes on the conversion and expect to move into a higher tax bracket in the future. If you inherit a Roth, you can roll it into your own Roth and let the money grow tax-free until you need it. There are no minimum withdrawal requirements for Roths. - Transfer the funds into an inherited IRA

You may want to consider this option if you’re younger than 59½ and need money to pay expenses. If you roll the funds into your own IRA and take withdrawals before age 59½, you’ll pay taxes on the withdrawals as well as a 10% early-withdrawal penalty. By transferring the funds to an inherited IRA, you won’t get hit with the early-withdrawal penalty. You’ll be required to take distributions from your inherited IRA, based on your life expectancy, but you have the option of postponing them until the latter of the year your spouse would have turned 73 or December 31 in the year following your spouse’s death. You’ll also have the option of rolling the account into your own IRA after you turn 59½. This will allow you to postpone distributions until you reach the age at which you’re required to take RMDs

How to leave children a tax-friendly legacy

Although your adult children are unlikely to complain if you leave them a large inheritance, taxes could significantly reduce the amount they’ll ultimately receive. Non-spouse heirs will be required to deplete an inherited IRA in 10 years. They may also have to take the required minimum distributions in years one through nine. Depending on their income, these withdrawals could vault them into a higher tax bracket. If you’d like to lighten that burden, one strategy is to convert some of the funds in your traditional IRA to a Roth. Non-spouse heirs are required to deplete a Roth within 10 years, but withdrawals are tax-free. Better yet, because the original owner isn’t required to take RMDs, your heirs won’t have to take them, either. They can leave the funds alone until the 10th year, allowing the money to grow tax-free, or take withdrawals as needed, without worrying about a tax hit. Before converting any funds, compare your tax rate with those of your heirs. If your tax rate is much lower, converting some of your IRA funds to a Roth could make sense.

The math is less compelling if your heirs’ tax rate is lower than yours, particularly if a conversion would kick you into a higher tax bracket. Be aware, too, that a large Roth conversion could trigger higher Medicare premiums and taxes on your Social Security benefits. A less costly strategy: Consider which heirs will benefit most from inheriting a traditional IRA. In addition to spouses, certain other heirs — including minor children — can still stretch out withdrawals over their lifetime. Consider the financial status of your beneficiaries. You may want to bequeath your IRA to an adult child who is in a low tax bracket, for instance, and give other assets to a child who earns a six-figure income. Your heirs will owe little or no tax on investments and other assets that aren’t held in tax-deferred accounts. The cost basis for these assets is “stepped up” to their value on the day of the original owner’s death. For example, if you paid $50 for a share of stock and it’s worth $250 on the day you die, your heirs’ basis will be $250. If they sell the stock immediately, they won’t owe any taxes. The step-up also applies to the value of your family home (and any other property you inherit), a big benefit at a time when many older homeowners have seen the value of their homes skyrocket.

Note: This item first appeared in Kiplinger's Personal Finance Magazine, a monthly, trustworthy source of advice and guidance. Subscribe to help you make more money and keep more of the money you make here.

Read more

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Block joined Kiplinger in June 2012 from USA Today, where she was a reporter and personal finance columnist for more than 15 years. Prior to that, she worked for the Akron Beacon-Journal and Dow Jones Newswires. In 1993, she was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She has a BA in communications from Bethany College in Bethany, W.Va.

-

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market Today

Dow Adds 1,206 Points to Top 50,000: Stock Market TodayThe S&P 500 and Nasdaq also had strong finishes to a volatile week, with beaten-down tech stocks outperforming.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

It's Time to Rethink What 'Aging Well' Means

It's Time to Rethink What 'Aging Well' MeansDon’t fall into the trap of thinking there is a "right way" to age. Here's how to reframe aging in a healthy, achievable way.

-

The New Rules of Retirement

The New Rules of RetirementPopular guidelines about how to save, invest and spend need to be updated and personalized to ensure you'll never run out of money.

-

I’ve Played 1,300-plus Golf Courses: These Are the 4 on My 'Must-Play' List for 2026

I’ve Played 1,300-plus Golf Courses: These Are the 4 on My 'Must-Play' List for 2026These four luxury golf courses offer an extraordinary experience for players this year.

-

How to Plan a (Successful) Family Reunion

How to Plan a (Successful) Family ReunionFrom shaping the guest list to building the budget, here's how to design a successful and memorable family reunion.

-

Is Direct Primary Care Right for Your Health Needs?

Is Direct Primary Care Right for Your Health Needs?With the direct primary care model, you pay a membership fee for more personalized medical services.

-

Smart Ways to Share a Credit Card

Smart Ways to Share a Credit CardAdding an authorized user has its benefits, but make sure you set the ground rules.

-

Tip: Ways to Track Your Credit Card Rewards

Tip: Ways to Track Your Credit Card RewardsHere are the best strategies and apps to help you stay current with your credit card rewards.

-

What to Do If You Plan to Make Catch-Up Contributions in 2026

What to Do If You Plan to Make Catch-Up Contributions in 2026Under new rules, you may lose an up-front deduction but gain tax-free income once you retire.