What Superagers Know That You Don't

Research on superagers is helping everyone age better. Here's how some superagers stay sharp and how you can join a superager study.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

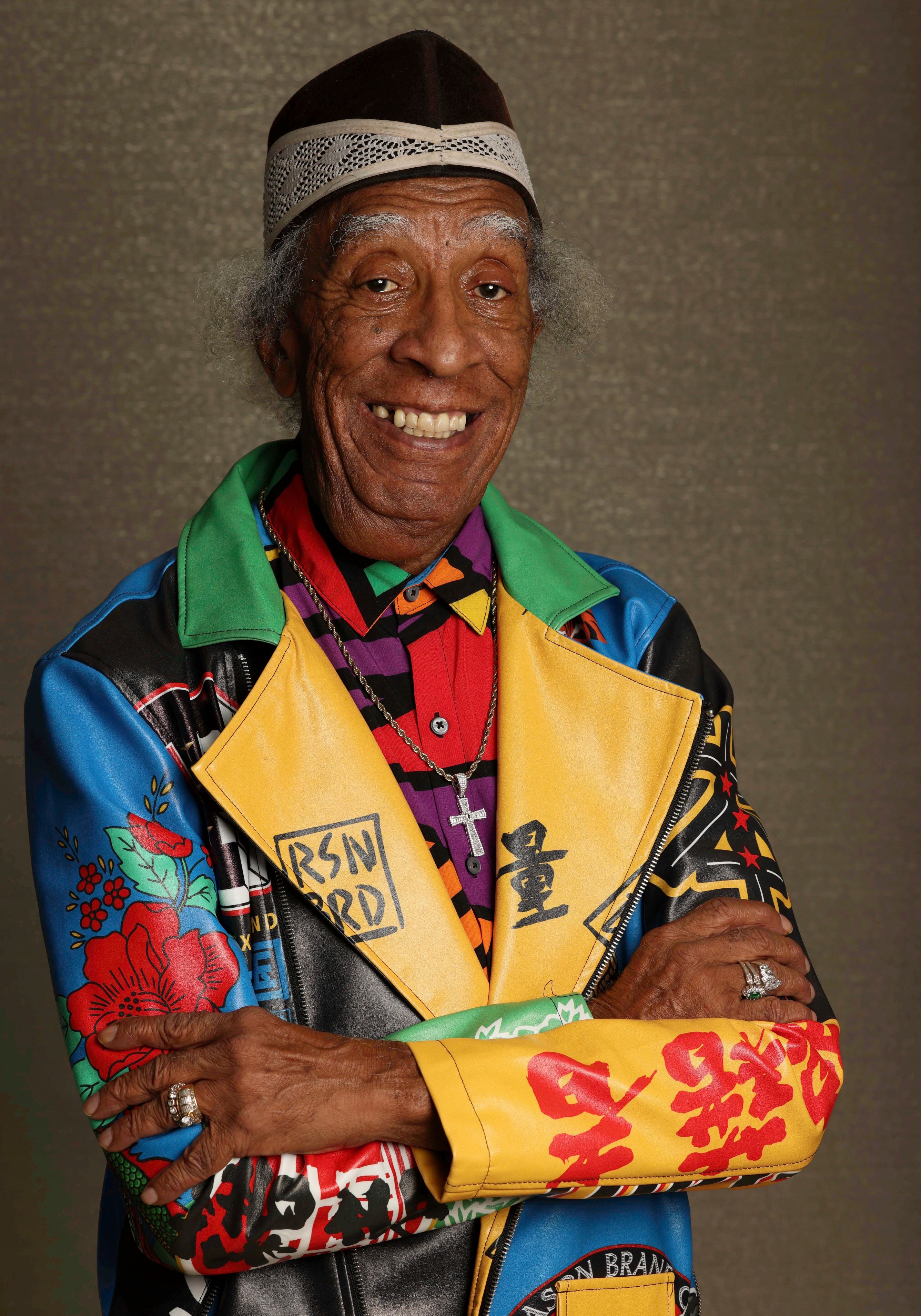

William Scott, who is about to turn 85, plans his busy days months ahead. At 5:30 every morning, he prepares what he calls his “A to Z schedule,” planning how he’ll take on the world. He lectures on double-decker buses touring Chicago, serves on community advisory boards and takes advantage of everything his city has to offer. “There isn't anyone from the mayor to the governor whose meetings I don't tend to be in the first row to ask questions,” he says, “and they all know me by sight.”

Seeming to defy the effects of age, Scott is considered a superager — someone 80 or older with the cognitive abilities of someone about 30 years younger. Researchers are studying Scott and other superagers, hoping to unlock their secrets and help the rest of us maintain brain health and avoid dementia as we grow older.

We've profiled a number of inspiring superagers here. You will also find guidance on how to determine your odds of joining their ranks and how to join a superager study at the end of this article.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Samuel Bender celebrates his 109th birthday.

At 109, superager Samuel Bender doesn’t get around as well as he used to. He uses a walker and a transport chair and doesn’t leave his Providence, R.I., condo complex much. But the retired veterinarian continues to charm women in his retirement community; he socializes and plays Scrabble with friends and occasionally lifts small weights. He continues to vote in presidential elections because he was raised to believe that’s the responsible thing to do.

Susan Alitto is almost 86.

Superager Susan Alitto, who will soon turn 86, has been retired from her hospital administration job for only a few years. She volunteers for Hyde Park Village in Chicago, a program she helped found that provides services for older people. She gives rides and organizes activities. In her leisure time, she goes to concerts, theaters and museums, she says, “often with friends, but if I don't have anyone to go with, I'll go by myself.”

Looking for patterns in superaging

“Our oldest superager is 110.5,” says one top researcher, neurologist Emily Rogalski, referring to the study she heads, the SuperAging Research Initiative, which is based in Chicago and enrolls people in multiple states and in Canada. “And I had the opportunity to visit her and she shared some homemade wine that she made. We have another superager who's in her mid-90s and last year did a semester at sea with college students and then went hiking and building houses and (traveling) in other countries.”

Both Scott and Alitto participate in the SuperAging Research Initiative, which is aimed at uncovering the factors that contribute to extended healthspan and that may avoid Alzheimer’s and its effects.

Stacy Andersen co-directs the New England Centenarian Study at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. She says researchers there look at superaging among people aged 100 or more; the oldest participant died at 119. Her research project has enrolled about 300 centenarian superagers — including Bender — with a goal of studying 1,000.

“These people have a different aging trajectory,” Andersen says, “and so we're trying to find enough of these cognitive superagers so that we can look at what are the patterns in biology or behavior and lifestyle or environment that have led these people to become cognitive superagers.”

Scott is the personification of a different aging trajectory. A history and social studies teacher, as well as a lecturer and community activist, Scott semi-retired after a bad bout of triple pneumonia sidelined him in November. But his semi-retired status doesn’t mean he sits home. “I work with everything in Chicago," he says, including Rainbow PUSH, Saint Sabina Church and his government representatives at all levels.

As for what animates him, Scott paraphrases “Grapes of Wrath,” saying “Injustice anywhere affects me, period… I don't just clutch my throat and say, ‘Oh, isn't that terrible about what is going on in Washington, D.C.?’ I get involved.”

Making aging cool

Rogalski says superagers are influencing how researchers look at aging in general. “The way that we used to think about aging was that everyone was going to get old and senile,” says Rogalski, who has been studying superagers for 20 years. But Rogalski says that way of thinking is overly simplistic.

It’s true that cognition typically declines with aging, Rogalski adds, but dementia is not the norm. A small portion of older people maintain their brains’ performance for virtually their entire lives.

Public awareness of superaging may help shape attitudes about growing older, Rogalski says. “The expectation is that everything that happens when you get older is bad,” she says, “and if we can start to create a dent in the stigma around aging, that is fantastic.”

More superagers on the way

While their numbers may be increasing as baby boomers grow older, superagers still make up a relatively small portion of the population. Rogalski says less than 10% of 80-year-olds who think they have great memories qualify after being screened to participate in the superaging initiative. Andersen says that while about 50% of centenarians have dementia, about one in five is a superager.

There are more than 100,000 people in the U.S. who have reached the age of 100, which means there are roughly 20,000 centenarian superagers. This population of what might be called super-superagers is “the best group of people to be studying how we can all extend our cognitive health span and avoid Alzheimer's disease,” Andersen says.

For example, some superagers are genetically at risk for Alzheimer’s, according to Rogalski, but they manage to escape its onset. She says this suggests “there may be protective factors from a genetic standpoint, which have yet to be discovered, that are contributing to their cognitive trajectory.

“So these things could contribute at some point to helping people increase their odds of becoming a superager or we think that what we learn from superagers has the possibility to spur new investigations from lifestyle interventions to pharmacological interventions. And those give us opportunities to increase the probability that someone will live long and live well.”

Superagers helping others

Superagers Scott, Bender and Allitto enrolled in their respective studies to help their aging peers and those who come after them.

Scott, for one, is determined to change how a lot of people age; he gives lectures on topics including “senior empowerment, senior activism, seniors and an alternative to what I refer to as the sin of doing nothing.”

He’s dismayed that most residents of his senior living complex never go out. “There's a nonstop activities calendar in Chicago, which too many seniors, in my personal opinion, don't participate in.”

Alitto is part of a nationwide effort known as the village movement, which aims to help people age in place by providing services, social contacts and support needed in their specific communities. She was the founding president of Hyde Park Village in its namesake Chicago neighborhood, which charges as little as $125 a year and offers things like companions for medical appointments, check-ins, tech support and memory support programs.

Alitto describes herself as a very active volunteer and says she still serves on the board. “It's probably time to step down and let younger people move in,” she says, “but I've got very strong ideas about what I think we should do or shouldn't do, and so I sort of stayed there to keep my two cents in there.”

Scott reaches across generations, working with other superagers and a group of 25 called ICE, which stands for intergenerational collaborative engagement. “We dialogue with young people in high schools, colleges, elementary schools…and also in shopping malls, when people are just walking by.”

They invite the younger people to “sit down and chat with a senior.”

The best question, he says, is “How do you feel getting up and aging and knowing you're going to die soon?”

“I say, ‘I worry more about you getting to 18 without getting shot in Chicago than about me dying.’ “

Donating brains

One significant way the superagers are helping others is by consenting to donate their brains to researchers in their respective studies, something the vast majority of enrollees have done, including Scott and Alitto, as well as Bender and his daughter.

“When an individual gives that great gift of donating their brain, it really allows us to conduct cellular and molecular investigations that just aren't possible during life,” Rogalski says.

Andersen says the most striking thing researchers have discovered about super-superagers is that their physical brains are more like the brains of younger people, with less atrophy, less shrinkage and a thicker cortex, compared to the brains of peers. “So it does seem like not only is their cognitive aging different, but their brain aging is different.”

Andersen continues, “What's fascinating is that some of them have the Alzheimer's pathologies in their brains, so they have evidence of amyloid and tau (proteins associated with the disease), yet these people were cognitively stellar.”

Rogalski says superager initiative researchers examining brains: “see that some of their cellular features are also distinct. So the size of some of their neurons and the density or the number of a special type of cell called von Economo neurons is also greater.”

Yaakov Stern is a neuropsychology professor at the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. While he doesn’t specifically work with superagers, part of his research focuses on what he describes as “the concept of cognitive reserve, which is essentially how some people can cope with age and disease-related brain changes better than others.”

In addition, Stern says, some people don’t experience the amount of age-related change in their brains as others, which he calls “brain maintenance.

Intellectual community

Sam Bender, the 109-year-old retired veterinarian, lives in a condominium complex with retired Brown University professors, physicians, teachers and attorneys, who provide intellectual stimulation to each other.

Bender has cared for the pets of some prominent people, including Clarence B. Jones, who was Martin Luther King Jr.’s lawyer, speechwriter and confidant. He also cared for four-time Communist presidential candidate Gus Hall’s dog.

When Caroline Kennedy’s father was president, her pony, Macaroni, fell on White House grounds, injuring its leg, Bender says. “One of my New York clients evidently was connected with some of the affairs going on in Washington and with the Kennedys,” Bender says. The client asked for help with the pony, wanting to keep the injury quiet. So Bender provided a salve for the injury.

But when asked to name the most remarkable thing he’s done in his life, Bender — father of three, grandfather of five and great-grandfather of ten —says without hesitation, “My family.”

Until a couple of years ago, Bender says, he went to the gym every day and frequently swam laps in the pool — past the age of 100.

Bender’s granddaughter, Jacqueline Brecht, 52, says the women in his community fawn over him. She says she encouraged him once to form a relationship with one of them. His response: “Right now I've got about 30 women who adore me and always want to come over and have dinner. If I coupled up with one of them, I'd have one of them who adored me and 29 of them who were angry at me.”

Note: This item first appeared in Kiplinger Retirement Report, our popular monthly periodical that covers key concerns of affluent older Americans who are retired or preparing for retirement. Subscribe for retirement advice that’s right on the money.

Are you a superager? Here's how to find out.

Get screened to participate in:

The SuperAging Initiative: https://haarc.center.uchicago.edu/join-our-research/

Email: superagingresearch@uchicago.edu

Phone:773-795-1111

The Centenarian Study: www.bumc.bu.edu/centenarian/radco/

Email: agewell@bu.edu

Phone: 1-888-333-6327

Bonuses:

Here’s a website to help plan your life ahead: www.planyourlifespan.org/

Read More on Superagers and Longevity

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Elaine Silvestrini has worked for Kiplinger since 2021, serving as senior retirement editor since 2022. Before that, she had an extensive career as a newspaper and online journalist, primarily covering legal issues at the Tampa Tribune and the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey. In more recent years, she's written for several marketing, legal and financial websites, including Annuity.org and LegalExaminer.com, and the newsletters Auto Insurance Report and Property Insurance Report.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost You

Betting on Super Bowl 2026? New IRS Tax Changes Could Cost YouTaxable Income When Super Bowl LX hype fades, some fans may be surprised to learn that sports betting tax rules have shifted.

-

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026

How Much It Costs to Host a Super Bowl Party in 2026Hosting a Super Bowl party in 2026 could cost you. Here's a breakdown of food, drink and entertainment costs — plus ways to save.

-

It's Time to Rethink What 'Aging Well' Means

It's Time to Rethink What 'Aging Well' MeansDon’t fall into the trap of thinking there is a "right way" to age. Here's how to reframe aging in a healthy, achievable way.

-

The New Rules of Retirement

The New Rules of RetirementPopular guidelines about how to save, invest and spend need to be updated and personalized to ensure you'll never run out of money.

-

I’ve Played 1,300-plus Golf Courses: These Are the 4 on My 'Must-Play' List for 2026

I’ve Played 1,300-plus Golf Courses: These Are the 4 on My 'Must-Play' List for 2026These four luxury golf courses offer an extraordinary experience for players this year.

-

What to Do If You Plan to Make Catch-Up Contributions in 2026

What to Do If You Plan to Make Catch-Up Contributions in 2026Under new rules, you may lose an up-front deduction but gain tax-free income once you retire.

-

You Saved for Retirement: 4 Pressing FAQs Now

You Saved for Retirement: 4 Pressing FAQs NowSaving for retirement is just one step. Now, you have to figure out how to spend and maintain funds. Here are four frequently asked questions at this stage.

-

3 Trips to Escape the Winter Doldrums, Including An Epic Cruise

3 Trips to Escape the Winter Doldrums, Including An Epic CruiseThree winter vacation ideas to suit different types of travelers.

-

What Science Reveals About Money and a Happy Retirement

What Science Reveals About Money and a Happy RetirementWhether you’re still planning or already retired, these research-based insights point the way to your best post-work life.

-

How to Leave Different Amounts to Adult Children Without Causing a Rift

How to Leave Different Amounts to Adult Children Without Causing a RiftHere’s how to leave different amounts to adult children without causing a family rift.