How Long? How Often? 10 Facts About Economic Recessions

Fears of an economic downturn are once again on the rise, but what is a recession, exactly? We tackle this and other questions here.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Despite years of warnings on the part of economists, strategists and other market pros, the U.S. economy has thus far avoided falling into a recession.

True, the economy may not feel that great to the legions of folks struggling with inflation – but both official and unofficial measures confirm that we're not currently in a downturn.

True, the jobs market is showing signs of slowing down, increasing the odds of a cut to the short-term federal funds rate later this year. Meanwhile, trade policy is contributing to sticky inflation.

So far, however, the U.S. economy has been remarkably resilient.

And yet poll after poll shows that Americans have serious doubts about the health of the economy. Given this disconnect between economic realities and the nation's general mood, it's fair to ask: if this isn't a downturn, then just what is a recession, anyway?

Well, for one thing, a recession is the scariest creature in the average investor's closet of anxieties. There's little wonder why. People fear recessions because they can mean lower home prices, lower stock prices – and, of course, unemployment.

It's also not very reassuring that any number of things can cause or exacerbate a recession: an exogenous shock, such as the COVID-19 crisis or the Arab oil embargo of 1973; soaring interest rates; or ill-conceived legislation, such as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

The bottom line, however, is that recessions are a fact of life. As highly unpleasant as they may be, they are inevitable occurrences in any dynamic economy. And if you're prepared for the next recession, there will be plenty of opportunities when that downturn ends. Thus, the more you know about recessions, the better.

Here are 10 must-know facts that help answer the question, What is a recession?

1. Why are they called recessions?

Because calling them "depressions" is too scary. No, really.

After the Great Depression – a term once considered milder than "panic" or "crisis" – the term "depression" for an economic downturn seemed particularly terrifying. Economists began to use the term "recession" instead.

Currently, "depression" is used to mean an extremely sharp and intractable recession, but there is no formal definition of the term in economics.

The Pandemic Recession included levels of unemployment not seen since before World War II. And the 2007-09 recession certainly had uncomfortable similarities to the Great Depression, in that it involved a financial crisis, extremely high unemployment, and falling prices for goods and services. Economists now call it the Great Recession.

2. What constitutes an official recession?

Someone has to be the official arbiter of recessions and recoveries, and the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is that someone.

Although two quarters of consecutive gross domestic product (GDP) contraction is the standard shorthand for a recession, the NBER actually uses many indicators to determine the start and end of a recession.

In fact, GDP is not the committee's favorite indicator: It prefers indicators of domestic production and employment instead. Other signs of recession include declines in real (inflation-adjusted) manufacturing and wholesale-retail trade sales and industrial production. Prolonged declines in production, employment, real income and other indicators also contribute to the NBER's recession call.

In the case of the Pandemic Recession, NBER says: "The committee has determined that a trough in monthly economic activity occurred in the US economy in April 2020. The previous peak in economic activity occurred in February 2020. The recession lasted two months, which makes it the shortest U.S. recession on record."

3. How long do recessions typically last?

The average length of recessions going all the way back to 1857 is less than 17.5 months. Recessions actually have been shorter and less severe since the days of the Buchanan administration. The long-term average includes the 1873 recession – a kidney stone of a downturn that lasted 65 months. It also includes the Great Depression, which lasted 43 months.

If we look at the period since World War II, recessions have become less harsh, lasting an average of 11.1 months. In part, that's because bank failures no longer mean that you lose your life savings, thanks to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and because the Federal Reserve has gotten (somewhat) better at managing the country's money supply.

The longest post-WWII recession was the Great Recession, which began December 2007 and ended in June 2009, a total of 18 months. Conversely, the two-month Pandemic Recession helped nudge the average length of recession down a notch.

4. How often do recessions happen?

Again, since 1857, a recession has occurred, on average, about every three-and-a-quarter years. It used to be the government felt that letting recessions burn themselves out was the best solution for everyone concerned.

Since the end of World War II, the U.S has suffered through 12 recessions, or an average of one every 6.5 years. The last economic expansion, starting at the end of the Great Recession, lasted 128 months. By that measure, we were overdue for an economic retraction when the Pandemic Recession hit.

5. When was the harshest recession?

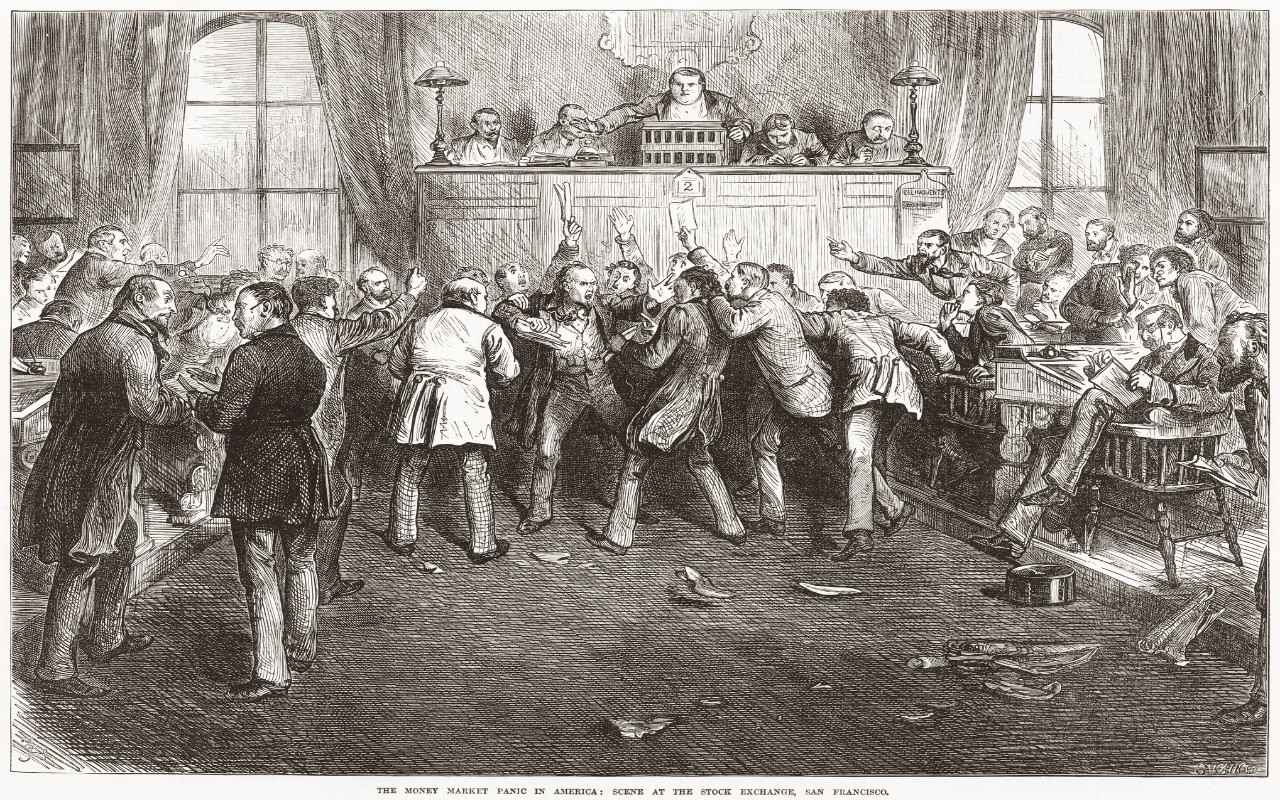

The recession of 1873 was actually known as the Great Depression until the 1929 recession rolled in.

The recession started with a financial panic in 1873 with the failure of Jay Cooke & Company, a major bank. The event caused a chain reaction of bank failures across the country and the collapse of a bubble in railroad stocks. The New York Stock Exchange shut down for 10 days in response. The recession lasted until 1877.

6. What is the worst effect of a recession?

An old economist joke is that a recession is when someone else loses their job, and a depression is when you lose your job. (Very few economists have transitioned to stand-up comedy.)

Your job is your main source of income, and that's why it's important to have a few months' salary in cash as an emergency fund – especially since jobs are increasingly hard to come by in a recession.

7. When is the best time to buy stocks in a recession?

Historically, the best time to buy stocks is when the NBER announces the start of a recession. It takes the bureau at least six months to determine if a recession has started; occasionally, it takes longer. The average post-WWII recession lasts 11.1 months. Often, by the time the bureau has figured out the start of the recession, it's close to the end. Many times, investors anticipate the beginning of a recovery long before the NBER does, and stocks begin to rise around the time of the actual economic turnaround.

For instance, the Great Recession was officially announced on December 1, 2008 – a full year after it had started. The recession ended in June 2009; the bear market ended three months earlier, on March 6, 2009. The ensuing bull market lasted more than a decade.

In the most recent case, the NBER called the end of the Pandemic Recession on July 19, 2021, or 15 months after it ended. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 gained 50% from April 30, 2020 to July 14, 2021.

8. What’s the best thing to do with your money during a recession?

Pay off your credit card debt. Here's why: Paying off a credit card that charges 18% interest is the rough equivalent of getting an 18% return on your investment, and you’re not going to get that from most other investments during a recession.

That said, bond prices typically rise in value during a recession – provided the recession isn’t sparked by rising interest rates. Recall that in 2022, when the Fed began raising interest rates at the fastest pace in more than four decades, bonds took a nosedive.

9. What is the best early warning sign of a recession?

More than the stock market, consumer confidence or the index of leading economic indicators, an inverted yield curve has been a solid predictor of economic downturns.

That is, at least until fairly recently.

An inverted yield curve is when short-term government securities, such as the three-month Treasury bill, yield more than the 10-year Treasury bond. This indicates that bond traders expect weaker growth in the future. The U.S. curve has inverted before each recession in the past 50 years, with just one false signal.

The yield curve was inverted for more than two years through late 2024, but a recession has yet to materialize. Whether this is another false signal remains to be seen.

The index of leading economic indicators is a composite of 10 indicators – including the stock market and consumer confidence – and is useful for those who want a broader view of the economic picture.

10. Does the Federal Reserve cause recessions?

Officially, the Fed never wants to start a recession, because part of its dual mandate is to keep the economy strong.

Unfortunately, the other part of the Fed's dual mandate is to keep inflation low. The main cure for soaring inflation is higher interest rates, which slows the economy.

In 1981, the Fed hiked interest rates so high that three-month T-bills yielded more than 15%. Those rates put the brakes on the economy and ended inflation – at the price of a short but sharp recession.

Related content

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Dan Burrows is Kiplinger's senior investing writer, having joined the publication full time in 2016.

A long-time financial journalist, Dan is a veteran of MarketWatch, CBS MoneyWatch, SmartMoney, InvestorPlace, DailyFinance and other tier 1 national publications. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Consumer Reports and his stories have appeared in the New York Daily News, the San Jose Mercury News and Investor's Business Daily, among many other outlets. As a senior writer at AOL's DailyFinance, Dan reported market news from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Once upon a time – before his days as a financial reporter and assistant financial editor at legendary fashion trade paper Women's Wear Daily – Dan worked for Spy magazine, scribbled away at Time Inc. and contributed to Maxim magazine back when lad mags were a thing. He's also written for Esquire magazine's Dubious Achievements Awards.

In his current role at Kiplinger, Dan writes about markets and macroeconomics.

Dan holds a bachelor's degree from Oberlin College and a master's degree from Columbia University.

Disclosure: Dan does not trade individual stocks or securities. He is eternally long the U.S equity market, primarily through tax-advantaged accounts.

-

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax Deductions

Ask the Tax Editor: Federal Income Tax DeductionsAsk the Editor In this week's Ask the Editor Q&A, Joy Taylor answers questions on federal income tax deductions

-

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)

States With No-Fault Car Insurance Laws (and How No-Fault Car Insurance Works)A breakdown of the confusing rules around no-fault car insurance in every state where it exists.

-

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're Rich

7 Frugal Habits to Keep Even When You're RichSome frugal habits are worth it, no matter what tax bracket you're in.

-

The Best Precious Metals ETFs to Buy in 2026

The Best Precious Metals ETFs to Buy in 2026Precious metals ETFs provide a hedge against monetary debasement and exposure to industrial-related tailwinds from emerging markets.

-

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works Instead

For the 2% Club, the Guardrails Approach and the 4% Rule Do Not Work: Here's What Works InsteadFor retirees with a pension, traditional withdrawal rules could be too restrictive. You need a tailored income plan that is much more flexible and realistic.

-

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look Like

Retiring Next Year? Now Is the Time to Start Designing What Your Retirement Will Look LikeThis is when you should be shifting your focus from growing your portfolio to designing an income and tax strategy that aligns your resources with your purpose.

-

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your Stress

I'm a Financial Planner: This Layered Approach for Your Retirement Money Can Help Lower Your StressTo be confident about retirement, consider building a safety net by dividing assets into distinct layers and establishing a regular review process. Here's how.

-

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market Today

Stocks Sink With Alphabet, Bitcoin: Stock Market TodayA dismal round of jobs data did little to lift sentiment on Thursday.

-

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)

The 4 Estate Planning Documents Every High-Net-Worth Family Needs (Not Just a Will)The key to successful estate planning for HNW families isn't just drafting these four documents, but ensuring they're current and immediately accessible.

-

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)

Love and Legacy: What Couples Rarely Talk About (But Should)Couples who talk openly about finances, including estate planning, are more likely to head into retirement joyfully. How can you get the conversation going?

-

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares When You Are in the Minority Vote on a Sale of Substantially All Corporate Assets

How to Get the Fair Value for Your Shares When You Are in the Minority Vote on a Sale of Substantially All Corporate AssetsWhen a sale of substantially all corporate assets is approved by majority vote, shareholders on the losing side of the vote should understand their rights.