6 Ways to Improve Your Yield on Cash

Yields on most savings vehicles, such as bank deposit accounts and money market mutual funds, track the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

Yields on most savings vehicles, such as bank deposit accounts and money market mutual funds, track the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate. For seven miserable years, from 2008 to 2015, the fed funds rate was tantamount to zero—and that’s about what you got from your savings.

As the Fed has raised its benchmark rate, savings rates have risen with it. “This is a huge revelation to my clients,” says Jonathan Pond, a Newton, Mass., certified financial planner. “They are actually earning money on cash.”

Kiplinger expects the Fed to raise rates three times in 2019. Although interest rates on savings are still low, they have caught up with inflation and beat the dividend yield of Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index. And although cash may not yet be king when it comes to yields, it’s important to remember that the income it generates comes with little or no risk—providing a bit of respite from volatile stock and bond markets.

We found a number of options that will be a big improvement over your piggy bank.

Yields and prices are as of November 9.

Money Market Accounts

Don’t be discouraged if yields on your bank’s savings account and money market deposit account are still at rock-bottom. The national average savings account yields a miserly 0.09%, and the average MMDA pays just 0.20%, according to Bankrate.com. But you can find higher yields by shopping around—particularly at online banks and credit unions, which have lower overhead than traditional banks and can afford to pay a bit more.

For example, the online bank MemoryBank is a division of Republic Bank and Trust Co. Although it has no branch offices, you can access your money online and via 92,000 ATMs here and abroad without a surcharge. MemoryBank offers an MMDA that yields 2.25% and has no minimum balance requirement. The account does not offer check writing.

MySavingsDirect, another online bank, offers a savings account yielding 2.25%. Both savings accounts and MMDAs allow up to six withdrawals per month, but MMDAs can also offer account access via checks or debit cards.

Most important for conservative investors, both MMDAs and savings accounts are covered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Combined account balances at a single qualifying institution for an individual account owner are insured up to $250,000. Joint accounts are insured up to $250,000 per person. To see whether your money is fully covered, use the estimator at https://www5.fdic.gov/edie/.

Money Market Funds

These mutual funds invest in short-term, high-quality securities, such as certificates of deposit and Treasury bills. Unlike other mutual funds, whose share prices vary daily, money funds keep their share price constant at $1 and pay interest by issuing new shares or fractions of shares.

A money fund’s yield equals its earnings minus expenses, and it closely tracks short-term interest rates. The funds’ average 30-day yield is currently 1.82%, according to iMoneyNet. Most let you write checks on your account.

Choose funds with low expenses, because anything you pay for fund management comes out of your yield. A favorite: Vanguard Prime Money Market Fund (symbol VMMXX), which charges just 0.16% a year in expenses and currently yields 2.21%.

Savers in higher tax brackets should consider tax-free money funds, which invest in extremely short-term municipal IOUs. Because the interest is free from federal income taxes, the yields offered by tax-free money funds are lower than the yields of taxable money funds. Vanguard Municipal Money Market Fund (VMSXX), for example, currently yields 1.53%. But for savers in the top 40.8% tax bracket (for those subject to the surtax on net investment income), that’s the equivalent of 2.58%, or 2.43% for savers in the 37% bracket, so it makes sense for them to invest in Vanguard’s tax-free offering. Savers in the 24% tax bracket or lower, however, would be better off with Vanguard’s taxable money fund. Typically, a brokerage sweep account will sweep you into a money fund (or bank money market account) that pays less than what the broker’s other money funds offer. To get the higher-yielding money fund, you’ll have to move your money there after a trade.

Money funds aren’t covered by federal deposit insurance, but the funds have an impressive safety record. Few money funds have ever allowed their share price to drop below $1—“breaking the buck,” in fund parlance.

Certificates of Deposit

If you want a bit more interest than you can earn from MMDAs, savings accounts and money funds, consider certificates of deposit. In return for a higher interest rate, you agree to keep your money on deposit for a set amount of time. Typically, the bank will charge three months’ interest for early withdrawals from CDs with maturities of one year, and six months’ interest for withdrawing from CDs with longer maturities. (The penalty is tax-deductible, and banks will often waive penalties due to the death or incapacity of the account owner.) Usually, the longer the maturity, the higher the rate.

Be careful when choosing maturities. Currently, “one or two years is the sweet spot,” says Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com. The average two-year CD yields 0.94%, for example, and the average five-year CD yields 1.29%. The extra 0.35 percentage point probably isn’t worth locking up your money for half a decade, particularly when interest rates are likely to rise (see below for a strategy to take advantage of rising rates).

It pays to shop around for CDs, too. Although the average one-year CD yields 0.72%, the highest-yielding one-year CD with no minimum investment required, from CapitalOne 360 (www.capitalone.com), yields 2.60% with no annual fees. CapitalOne 360 also offers a two-year CD yielding 2.70%.

You can also buy CDs through a broker. Charles Schwab, Fidelity and Vanguard, for example, all offer CDs through a network of banks. You get to choose from a list of institutions, which makes shopping easy, and you can sell your CDs on the secondary market. Brokered CDs are fully FDIC-insured, and you can invest in several CDs from different banks, increasing the amount that’s protected by federal insurance. The minimum investment at most brokerages is $1,000.

If you buy a newly issued CD through the brokerage, you won’t pay a commission. You can sell your brokered CDs before they mature, but, as with bonds, you could lose interest and even principal on the deal if rates have risen since you bought the CDs.

Treasury Bills and Notes

In June 2011, three-month Treasury bills yielded as little as 0.01%. Thankfully, those days are gone, and the three-month T-bill now sports a respectable 2.36% yield.

Yields get better as maturities lengthen: A one-year T-bill yields 2.73%. A 10-year T-note yields just 3.19%. As with CDs, the best deals in Treasury securities are in shorter maturities. Ten years is a long time to tie up your money for an additional 0.46 percentage point of yield.

For conservative investors, T-bills are one of the safest investments on the planet. The federal government guarantees timely interest and principal payments on Treasury securities.

T-bills do have one unusual feature. They are sold at a discount from face value, and the difference between what you pay and the face value of the bill is your interest.

Investing in T-bills comes with some attractive tax benefits. First, interest is free from state income taxes. If you live in a high-tax state, such as California or New York, the state-tax savings can be substantial. And because T-bills don’t pay interest until they mature, you don’t owe taxes on that interest until the year they mature. If you buy a one-year T-bill in 2019, your interest won’t be taxable until the 2020 tax year.

Although you can buy T-bills from a broker, you can also buy them without a fee at www.treasurydirect.gov, the government’s auction portal for individual investors.

You can boost your yield slightly by investing in Treasury notes, which mature in two to 10 years. A two-year note yields 2.94%. Unlike T-bills, however, Treasury notes pay interest semiannually. You can also buy them without a fee through Treasury Direct.

Savings Bonds

Savings bonds pay relatively little, but they have a few tax benefits. Like Treasury bills, savings bonds pay interest that is free from state taxes. You can choose to report income to the IRS annually or pay taxes when you cash them in. (You can even wait until they stop paying interest in 30 years.) If you use the proceeds for qualified education expenses, the interest is tax-free. But it’s probably best to skip savings bonds as part of a college savings program for a young child (see Savings Bonds for the Holidays?).

The interest rate on savings bonds isn’t great: 0.10% a year, although the Treasury guarantees you’ll double your money in 20 years, which works out to about 3.5%. There is a three-month interest penalty if you cash in a savings bond in the first five years you own it.

A better deal for savers might be I-bonds, which are savings bonds that are guaranteed to beat inflation. I-bonds pay a fixed rate of 0.50% plus an adjustment in principal value based on the Consumer Price Index. The current composite rate is 2.83%. Although inflation might overtake the fixed return from a savings bond, the government guarantees that you’ll whip inflation with an I-bond.

Ultrashort Bond Funds

These funds usually invest in securities that mature within one year. Typical ultrashort funds yield a bit more than money market funds. Unlike with money funds, the share prices of ultrashort funds can and do fluctuate. If you can’t stand the thought of losing money, an ultrashort fund isn’t for you.

Nonetheless, we like Vanguard Ultra-Short-Term Bond (VUBFX). It charges just 0.20% in expenses and yields 2.59%. The fund’s only losing quarter was a tiny 0.1% loss in the fourth quarter of 2015.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

-

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live By

5 Vince Lombardi Quotes Retirees Should Live ByThe iconic football coach's philosophy can help retirees win at the game of life.

-

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USA

The $200,000 Olympic 'Pension' is a Retirement Game-Changer for Team USAThe donation by financier Ross Stevens is meant to be a "retirement program" for Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

-

10 Cheapest Places to Live in Colorado

10 Cheapest Places to Live in ColoradoProperty Tax Looking for a cozy cabin near the slopes? These Colorado counties combine reasonable house prices with the state's lowest property tax bills.

-

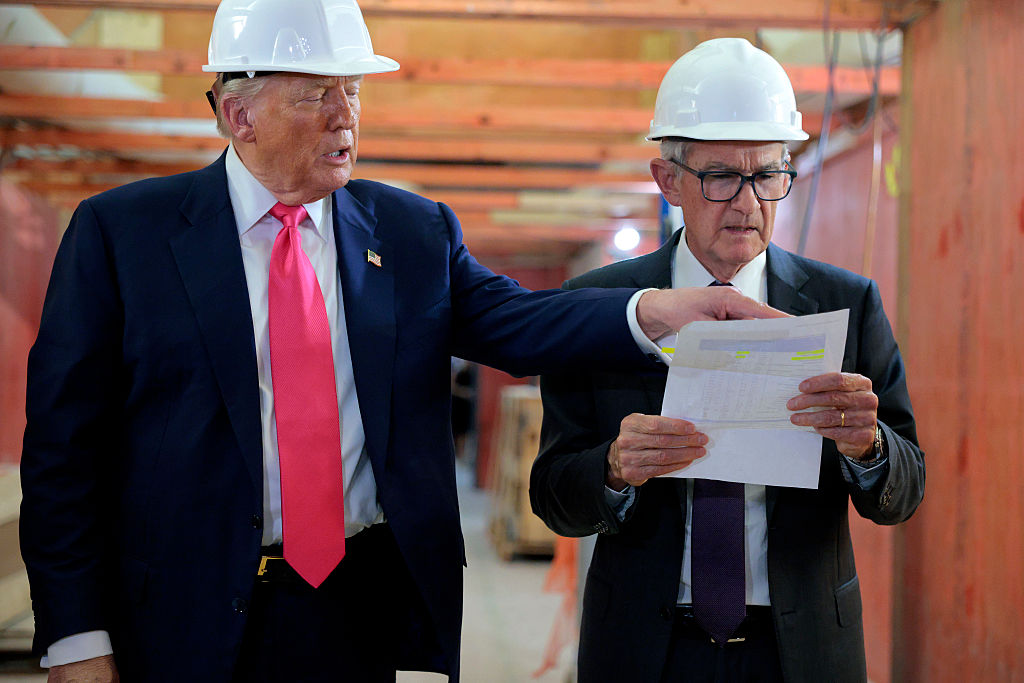

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to Know

The New Fed Chair Was Announced: What You Need to KnowPresident Donald Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his selection for the next chair of the Federal Reserve, who will replace Jerome Powell.

-

January Fed Meeting: Updates and Commentary

January Fed Meeting: Updates and CommentaryThe January Fed meeting marked the first central bank gathering of 2026, with Fed Chair Powell & Co. voting to keep interest rates unchanged.

-

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next Move

The December CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed's Next MoveThe December CPI report came in lighter than expected, but housing costs remain an overhang.

-

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?

How Worried Should Investors Be About a Jerome Powell Investigation?The Justice Department served subpoenas on the Fed about a project to remodel the central bank's historic buildings.

-

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed Meeting

The December Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Next Fed MeetingThe December jobs report signaled a sluggish labor market, but it's not weak enough for the Fed to cut rates later this month.

-

States That Tax Social Security Benefits in 2026

States That Tax Social Security Benefits in 2026Retirement Tax Not all retirees who live in states that tax Social Security benefits have to pay state income taxes. Will your benefits be taxed?

-

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising Prices

The November CPI Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for Rising PricesThe November CPI report came in lighter than expected, but the delayed data give an incomplete picture of inflation, say economists.

-

The Delayed November Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed and Rate Cuts

The Delayed November Jobs Report Is Out. Here's What It Means for the Fed and Rate CutsThe November jobs report came in higher than expected, although it still shows plenty of signs of weakness in the labor market.