How to Invest for a Higher-Tax Future

Use these strategies to boost your after-tax returns.

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Today

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more delivered daily. Smart money moves start here.

Sent five days a week

Kiplinger A Step Ahead

Get practical help to make better financial decisions in your everyday life, from spending to savings on top deals.

Delivered daily

Kiplinger Closing Bell

Get today's biggest financial and investing headlines delivered to your inbox every day the U.S. stock market is open.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Adviser Intel

Financial pros across the country share best practices and fresh tactics to preserve and grow your wealth.

Delivered weekly

Kiplinger Tax Tips

Trim your federal and state tax bills with practical tax-planning and tax-cutting strategies.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Retirement Tips

Your twice-a-week guide to planning and enjoying a financially secure and richly rewarding retirement

Sent bimonthly.

Kiplinger Adviser Angle

Insights for advisers, wealth managers and other financial professionals.

Sent twice a week

Kiplinger Investing Weekly

Your twice-a-week roundup of promising stocks, funds, companies and industries you should consider, ones you should avoid, and why.

Sent weekly for six weeks

Kiplinger Invest for Retirement

Your step-by-step six-part series on how to invest for retirement, from devising a successful strategy to exactly which investments to choose.

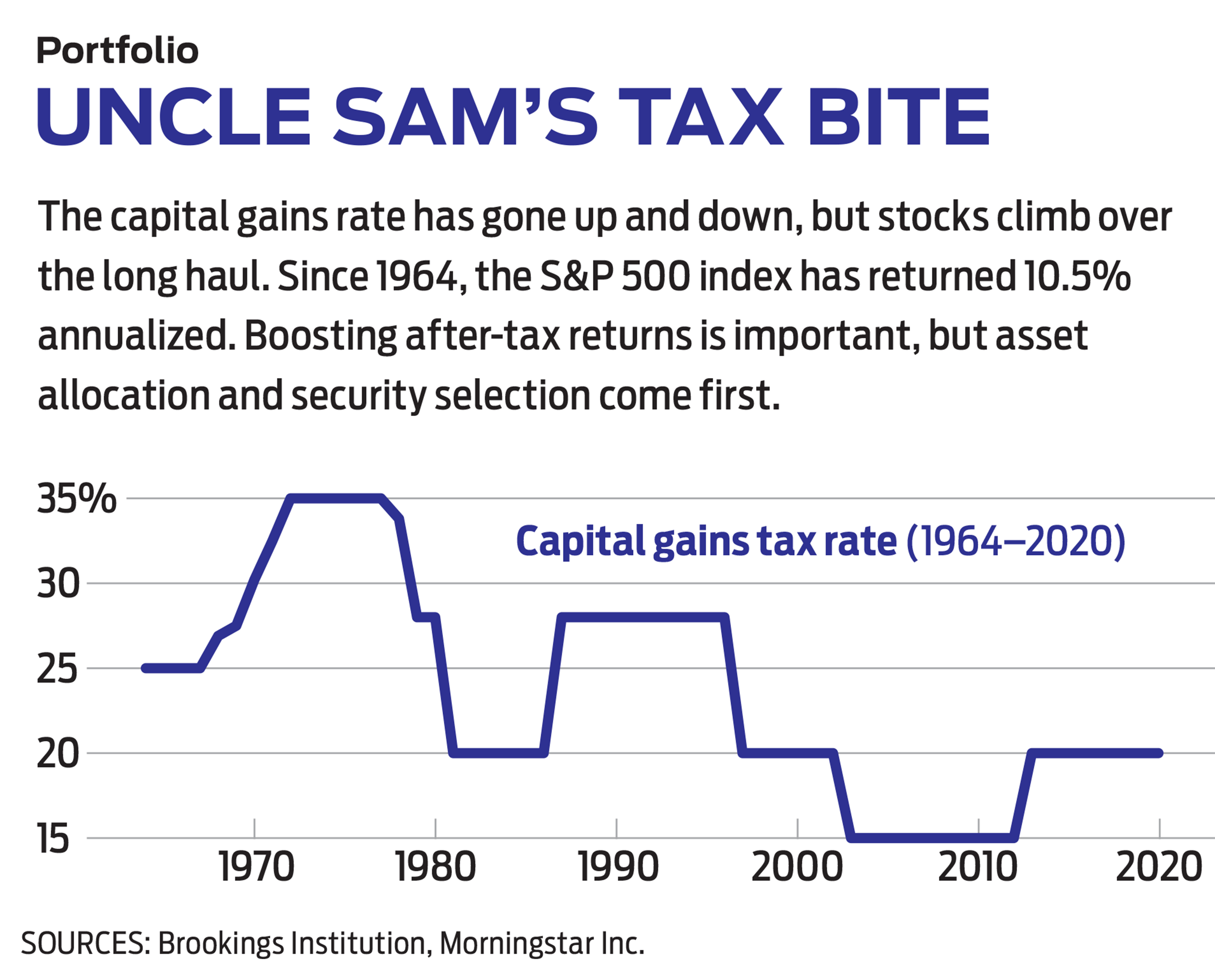

We all know what they say about the certainty of taxes. And this year, it’s a good bet that some taxes on investment income will rise—the biggest uncertainty is by how much. That makes now a good time to review some tax-wise investing strategies.

President Biden’s American Families Plan proposes to nearly double the long-term capital gains tax for the wealthiest taxpayers, from 20% to 39.6%. Add the 3.8% net investment income tax that certain high-earning investors must pay, and the top capital gains rate would rise to 43.4%. The plan is merely a proposal, of course; the final rate may land closer to 24% to 28%, say some experts.

Smart investors won’t make major portfolio changes right away. “I would not react to proposals,” says Joel Dickson, Vanguard’s head of Enterprise Advice Methodology. “Trying to predict what new taxes will look like is a fool’s errand,” he says. What’s more, the American Families Plan proposal would only affect taxpayers with annual income of $1 million or more, impacting “a small group of investors in a very small way,” says Dickson—and only in their taxable accounts, where capital gains taxes apply.

From just $107.88 $24.99 for Kiplinger Personal Finance

Become a smarter, better informed investor. Subscribe from just $107.88 $24.99, plus get up to 4 Special Issues

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Nevertheless, a tweak to your portfolio here and there could boost your after-tax returns, no matter how much money you earn. And what you save in taxes can grow and compound longer. “Tax management matters a lot,” says Bradley Clark, a certified financial planner in Andover, Mass. “It is more important for people in the highest tax brackets, but it is important for everyone.”

Smart moves, such as deciding whether to hold certain investments in a taxable or tax-deferred account, for instance, can help increase your after-tax returns. Some mutual funds and exchange-traded funds are more tax-efficient than others, too. Just try to avoid letting the tail wag the dog. “Ultimately, what matters is whether you have created wealth, not how much you have reduced taxes,” says Dickson.

Location matters

The most important decision investors make is about asset allocation—how much to invest in various asset classes. Tax-wise, asset location counts, too. Determining from a tax perspective which assets are best held in your IRA or in your taxable account is one way to minimize your overall tax bill. The strategy pivots around the way the IRS treats taxable and tax-deferred accounts. In taxable investment accounts, you pay taxes on annual dividend payouts and on any realized investment gains. In retirement accounts, such as traditional IRAs, 401(k)s and the like, you don’t owe Uncle Sam until money is withdrawn, at which time it’s taxed at ordinary-income rates.

The old-school approach to asset location was to use taxable accounts mostly for stocks and to use tax-deferred accounts for bonds. That’s because the assets are taxed in different ways. Stock dividend income is taxed at 0%, 15% or 20%, depending on your taxable income and filing status; gains on stock holdings are taxed at capital gains rates. Bond interest, however, is taxed as ordinary income.

But low bond yields have reduced the impact of this strategy. “The benefit has narrowed tremendously over the past decade,” Dickson says. Now, the strategy requires some fine-tuning within the broad asset groups.

For a start, not all bonds should be held in tax-deferred accounts. High-quality bonds, for instance, such as Treasuries and investment-grade corporate debt, can go in either a taxable account or an IRA, says Clark. But bonds that generate fat yields—high-yield corporate debt, bank loans and emerging-markets bonds—are best held in IRAs or other tax-deferred accounts to put off the tax bite at ordinary income rates.

The advice for stocks varies, too. Individual shares are best held in taxable accounts. That’s also the case for broad-market-index U.S. stock funds and international stock funds, especially if those funds pay dividends. You can qualify for a foreign tax credit from the IRS for any taxes your international stock fund pays on dividend income, but only if you hold the fund in a taxable account, says retirement income expert Clark.

But stock funds that frequently buy and sell holdings tend to generate big short-term capital gains distributions and should go into tax-deferred accounts. These so-called high-turnover funds include small-company stock funds, which must unload shares in winning stocks if the companies outgrow the fund’s parameter for market value. The same goes for real estate investment trusts because they generate non-qualified dividends, which are taxed as ordinary income.

Harvest your losses. Tax-loss harvesting involves selling investments that have gone down in value and replacing them with similar investments, using the losses to offset any realized investment gains to lower or eliminate your capital gains tax. Do it as needed to offset a significant gain in an investment you’ve sold in any given tax year. Match up short-term gains and losses and long-term gains and losses. And be mindful of the wash-sale rule—swapping into a similar investment is okay; buying an identical one is not. Or stockpile losses against future gains when the market takes a big downturn, as many active managers did in early 2020.

No gains? No worries. You can deduct up to $3,000 in losses from your income per year if you’re single or married filing jointly.

Pay sooner rather than later. Some call switching money from an IRA to a Roth IRA a tax-acceleration strategy, because you must pay income tax on the amount you convert. But it makes sense for some. “Pay taxes now to avoid a higher tax bill in the future,” says Dickson. The strategy works best if your current tax rate is lower than what you suspect you’ll pay in retirement. It may also work for the newly retired, says Clark. “Say you retire at 62 and don’t take Social Security until 70, and your income tax rate has dropped from 32% to 12%. Your tax rate has just gone on sale. Take the opportunity to do a Roth conversion.”

Find tax-efficient funds

Although taxes shouldn’t be a primary driver of investment decisions, choosing tax-efficient funds can improve your after-tax returns. Broadly speaking, large-company stock funds are more tax-efficient than small-company stock funds; growth funds fare better than their value-oriented brethren; and low-turnover index funds and ETFs, especially those that track broad market benchmarks, tend to shine over their actively managed counterparts. Vanguard Total Stock Market Index, which can be purchased as a mutual fund (symbol VTSAX) or ETF (VTI, $219), and iShares Core S&P 500 ETF (IVV, $424) are good choices for tax-conscious investors. For small companies, consider Vanguard S&P Small-Cap 600 ETF (VIOO, $208). Even some sector funds boast a low tax-cost ratio, a measure from research firm Morningstar of how much of a fund’s annualized return is eaten up by taxes due to capital gains distributions. Two examples are Invesco QQQ Trust (QQQ, $336) and Fidelity Nasdaq Composite ETF (ONEQ, $54).

Some myth-busting is in order when it comes to tax-managed funds. These funds include tax-efficiency as an investment objective and are marketed that way. But some critics pooh-pooh them: “Tax-managed funds have lost their relevance with the advent of very-low-cost ETFs. They’re a dinosaur,” says Dan Wiener, editor of the monthly newsletter The Independent Adviser for Vanguard Investors. Thomas Stapp, a certified financial planner in Olympia, Wash., stopped using them in his practice because, among other things, he found they performed no better than index funds.

But some of the funds deliver over the long haul and have appeal for tax-averse investors. Vanguard runs several funds focused on minimizing fund distributions, including Vanguard Tax-Managed Capital Appreciation (VTCLX), a large-company fund; Vanguard Tax-Managed Small Cap (VTMSX), a small-company focused fund; and Vanguard Tax-Managed Balanced (VTMFX), which holds 48% of its assets in stocks, 51% in bonds and 1% in cash. The managers chiefly employ tax-loss harvesting to minimize taxes. Over time, according to Morningstar, they have consistently minimized capital gains distributions to shareholders (relative to a comparable index fund) and still outperformed or kept pace over the long haul on an after-tax-return basis. Each fund has a bigger-than-usual $10,000 minimum.

Over the past decade, T. Rowe Price Tax-Efficient Equity (PREFX) has outpaced its peers (large-company growth funds) on a total-return basis in all but two years. The fund’s 13.1% after-tax return over the past decade through May trailed the Russell 1000 Growth index, but the fund outpaced its peers on an after-tax basis by an average of 1.1 percentage points per year. Says manager Don Peters, “Our fund is focused exclusively on after-tax return, whereas 99.9% of all other funds focus on pretax returns.” Investors typically lose two percentage points between pretax returns and after-tax returns, he says.

Actively managed funds can be tax-efficient, too. The four managers at American Century Focused Dynamic Growth (ACFOX) don’t officially use tax-conscious strategies to run the fund. But over the past three years, the fund’s 0.05% tax-cost ratio is a fraction of the 1.81% ratio of the typical large-company growth fund. The fund has a newly launched ETF sibling that trades with the symbol FDG.

Don’t make the mistake of shunning tax-inefficient funds out-of-hand—some are top performers. Over the past decade, Fidelity Contrafund cost shareholders more than double in taxes what Vanguard Total Stock Market Index did, according to Morningstar. But Contrafund’s 10-year annualized after-tax return of 12.9% (through May) beat the index fund’s 11.7% after-tax return. Funds with a history of throwing off big capital gains distributions that are nonetheless superior investments are perfect candidates for your tax-deferred account.

The muni conundrum. Municipal bonds are often thought of as the quintessential choice for tax-averse investors. The income these securities generate is free from federal taxes (and in some cases, free from state taxes, too), which makes them optimal for taxable accounts. But they’re not right for everybody. Low interest rates make these bonds and bond funds best for taxpayers in the top federal tax bracket who live in states with high taxes, says Clark, and have access to a low-cost, state-specific muni bond. Many fund firms, including Fidelity, Pimco and Vanguard, offer state-specific mutual funds. First Trust, Invesco and iShares offer California and New York muni-bond ETFs.

But the current market provides less upside for taxpayers in middle brackets. Consider: A broad muni-bond benchmark currently yields 0.82%. For investors in the 32% federal tax bracket, the tax-equivalent yield is 1.21%. That’s hardly compelling compared with the 1.50% yield on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond index. Other factors might make munis attractive for some—demand remains strong, and state and local economies are improving (see Income Investing). But tax-wise, says Clark, “Some people in low-tax states and low tax brackets are making that essential mistake of trying to minimize taxes instead of trying to maximize after-tax returns.”

Profit and prosper with the best of Kiplinger's advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and much more. Delivered daily. Enter your email in the box and click Sign Me Up.

Nellie joined Kiplinger in August 2011 after a seven-year stint in Hong Kong. There, she worked for the Wall Street Journal Asia, where as lifestyle editor, she launched and edited Scene Asia, an online guide to food, wine, entertainment and the arts in Asia. Prior to that, she was an editor at Weekend Journal, the Friday lifestyle section of the Wall Street Journal Asia. Kiplinger isn't Nellie's first foray into personal finance: She has also worked at SmartMoney (rising from fact-checker to senior writer), and she was a senior editor at Money.